Warnings from the fossil record

/Rochester Cathedral is constructed almost entirely from various types of limestone formed from the shells and remains of aquatic life that lived hundreds of million years ago. Despite its longevity, Earth’s fossil record holds a stark warning on the fragility of the natural world.

The pale yellow stone of the nave piers was quarried in Caen in Normandy in the 1130s. On many ashlars you can see bands of darker iron staining in the layers in which they were sedimented or deposited on the seabed, albeit compressed and stretched over time.

In other stone used around the Cathedral, particularly in the marble monuments in the floors and the tall, slander shafts of the east end, the fossils of a species of river snail can be clearly identified. Other types of fossils found around the Cathedral include shells, sea cucumbers and pieces of coral, of both extinct and surviving species.

Geology and archaeology

The evidence that geology and palaeontology of fossils provides for where stone has been quarried from is essential to understanding the construction of the building in the Middle Ages, and to its conservation today. Over twenty types of stone are identified to date from quarries around the British Isles and continental Europe.

When the Cathedral was rebuilt after the Norman conquest along with many other castles, cathedrals and churches, Tufa stone was used as a strong but relatively light and easily cut material. Tufa can now only be seen in the western, oldest part of the Crypt. Within just a few decades tufa deposits were depleted and stone began to be shipped from quarries in Caen in Normandy. The mid-12th century west end of the Cathedral is constructed from yellow Caen stone. After the loss of Normandy in 1204, its use was largely replaced in with Reigate stone quarried near Sussex. This is the grey-green stone used throughout the later east end.

The history of Earth is divided into a series of eons, eras and periods based on significant changes in the fossil record, extending back hundreds of millions of years. These changes were largely caused by mass extinction events; widespread and rapid decreases in the biodiversity of Earth. Evidence suggests each extinction event is probably related in some way to global atmospheric and oceanic events and abrupt climate change.

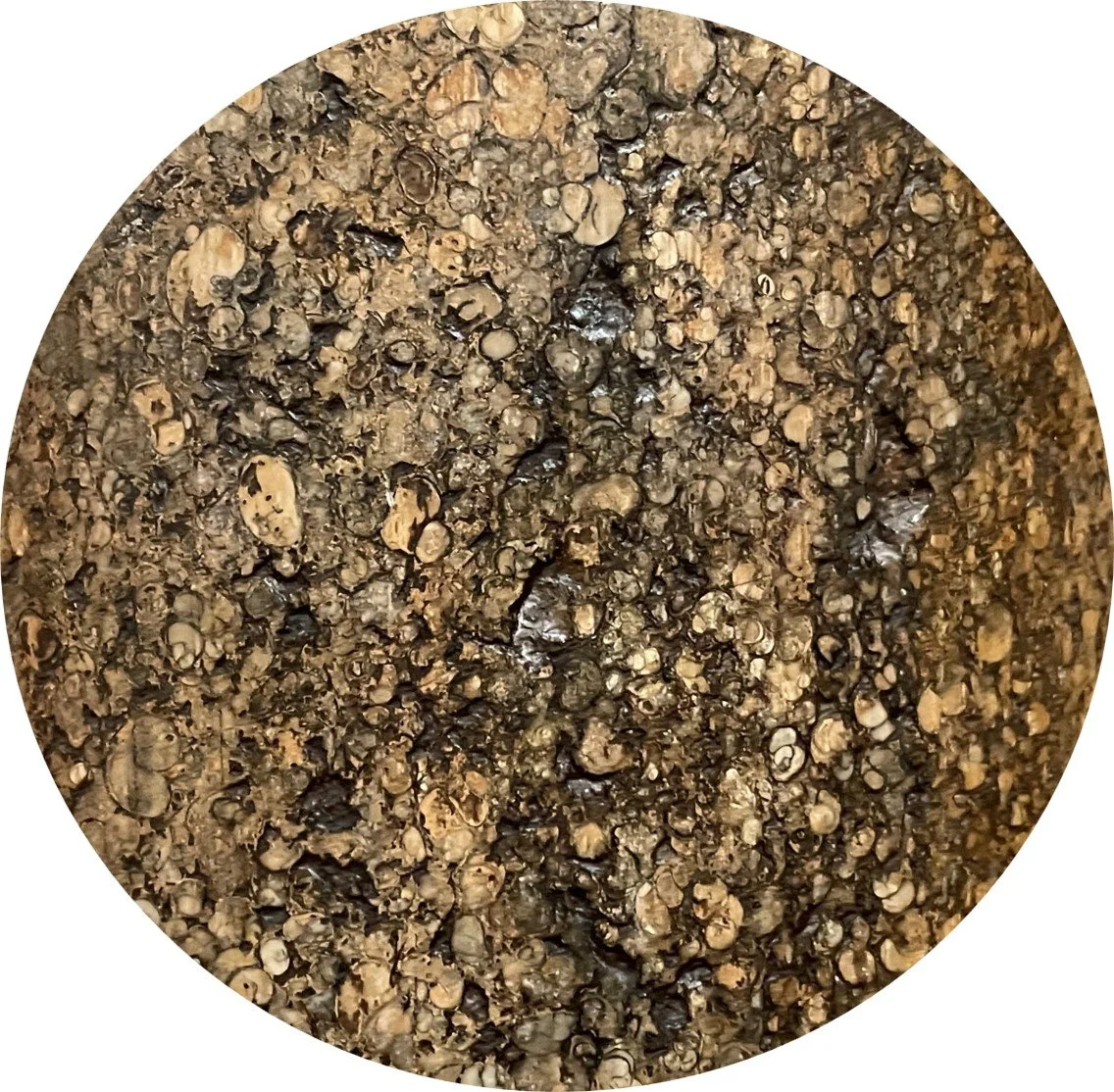

The brown marble used in the tall, slender shafts around the east end of the Cathedral was formed 100 million years ago in a region that is now off the coast of Dorset. The fine Jurassic limestone, not technically a marble, is quarried on the island of Purbeck. Purbeck marble can be seen to consist almost entirely of the shells of small aquatic creatures called Viviparus. The snails lived in a freshwater or brackish environment (less salty than sea water).

Sussex or Bethersden Marble is used extensively in the medieval brass casements; horizontal grave slabs for the wealthy or for prominent churchmen. When the floor of the nave was last re-laid in 1904 most of these slabs, long devoid of their brass ornaments, were gathered and laid in the Pilgrim’s Passage. It is another Jurassic-period limestone and not technically a true metamorphic marble. The larger size of the shells present in much Bethersden marble indicate these snails lived in a more freshwater environment with a lower acidity than those in the Purbeck marble.

The most well-known mass extinction event is undoubtedly the asteroid impact that caused the extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs around 66 million years ago. The beginning of the Jurassic period and the end of the preceding Triassic period around 201 million years ago was another mass extinction event associated with the start of volcanic eruptions in the central Atlantic, responsible for outputting a high amount of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere inducing profound global warming and ocean acidification. The start of the Triassic period and end of the Permian 252 million years ago is known as the Permian-Triassic extinction event and was associated with the volcanic eruption of the Siberian Traps causing widespread ocean acidification and anoxia.

The black Tournai marble used for the ledger stones throughout the west end of the Cathedral is even earlier, dating from the Lower Carboniferous period from 360 to 300 million years ago. This is the time that the first rainforests formed and several forms of life diverged. It was these abundant rainforests and swamps that formed much of the coal deposits in the British Isles, and it is from this we take the name Carboniferous.

A few Tournai marble ledgers throughout the nave feature the fossilized remains of aquatic creatures from this time, evidently distinct from those of the Jurassic period. The end of the Carboniferous period is marked by an abrupt period of climate change, which dramatically altered the distribution of these rainforests over just a few thousand years.

Five mass extinction events in total have been discerned in the fossil record, each thought to be associated in some way with global atmospheric and oceanic events and rapid climate change. Each caused profound and irreversible changes to the biosphere. Many species, when not forced to extinction, would take thousands to millions of years to recover.

Fossils in the Middle Ages

We might ask why the monks, masons and patrons of the Cathedral particularly chose stone with fossils for their architecture, memorials and even altars. They could not have known of the immense history of the stones they were selecting from around Europe, although they did recognise that many of the small shelled creatures entombed within belonged to the water – and so was often chosen to symbolise life, nature, and the elegant union of rock and water that is our world. Some also associated fossils, often found high on cliff faces and even atop mountains, of evidence of the biblical deluge flood.

The fossil record is characterised by changes in the environment and to life that have occurred in Earth’s long history, typically taking place over millions of years. It is also marked by mass extinction events that were catastrophic for biodiversity largely due to their abruptness, with environmental consequences in the air and sea that onset too rapidly for species and ecosystems to adjust.

The majority of greenhouse gas emissions from human activity have been since the start of the Industrial Revolution just 150 years ago - a blink of an eye on evolutionary timescales. It has been suggested that we are currently within Earth’s sixth mass extinction event, with human activity significantly decreasing biodiversity on a global scale. We must now heed the warnings from the fossil record and do what we can to minimise climate change and lessen our impact on the living world.

Jacob Scott

Research Guild

Find our what the Cathedral Gardeners are doing to boost biodiversity and keep the Gardens at the heart of the local environment in Rochester in How green are the Cathedral Gardens?

Find out more about the sustainability projects at Rochester Cathedral, recipient of the ROCHA Silver Eco Church Award.