The Rochester Bible, c.1125-1140

/

The Rochester Bible is a richly decorated manuscript produced by the monks of St Andrew’s Priory, Rochester. Now part of the British Library’s Royal Collection, the manuscript is on loan to Rochester Cathedral and features in the Beauty and the Beasts exhibition in the Cathedral Crypt.

The Rochester Bible – British Library, Royal MS 1 C VII – contains the Old Testament books of Joshua, Judges, Ruth, and I-IV Kings (also known as I and II Samuel and I and II Kings). During the medieval period, it was part of a Latin Vulgate set of five volumes, of which only it and a New Testament volume (‘Rochester New Testament’: Walters Art Gallery, MS. W.18) have survived.

The New Testament is written in the script of Christ Church, Canterbury but evidently its illumination (decoration) was carried out by Rochester monks. The Rochester Bible, however, was ‘a production solely of Rochester’ (Richards, p. 59). The twelfth- and thirteenth-century catalogues of the medieval priory library contain references to both of these volumes.

Mary P. Richards made a study of the two volumes in 1981, making a solid case for their relationship. She observes:

‘The two manuscripts would have been part of the earliest decorated bible recorded at Rochester. The [earlier] Gundulf Bible, the only other Vulgate listed in the catalogues, is an extremely plain and heavily corrected text. The new, decorated set was a ceremonial Vulgate reflecting the developing skills and resources of the Rochester see.’ (Richards, p. 66)

The work on the Rochester Bible may have commenced as early as c.1125, so is of particular significance to the Textus 900 celebrations commemorating the 900th anniversary of the legal encyclopaedia Textus Roffensis, which was produced at the priory around the same time.

The Rochester Bible is a splendid example of the work within twelfth-century monastic scriptoria generally, and shows us, in particular, the distinctive skills and productivity of the Rochester community at this time.

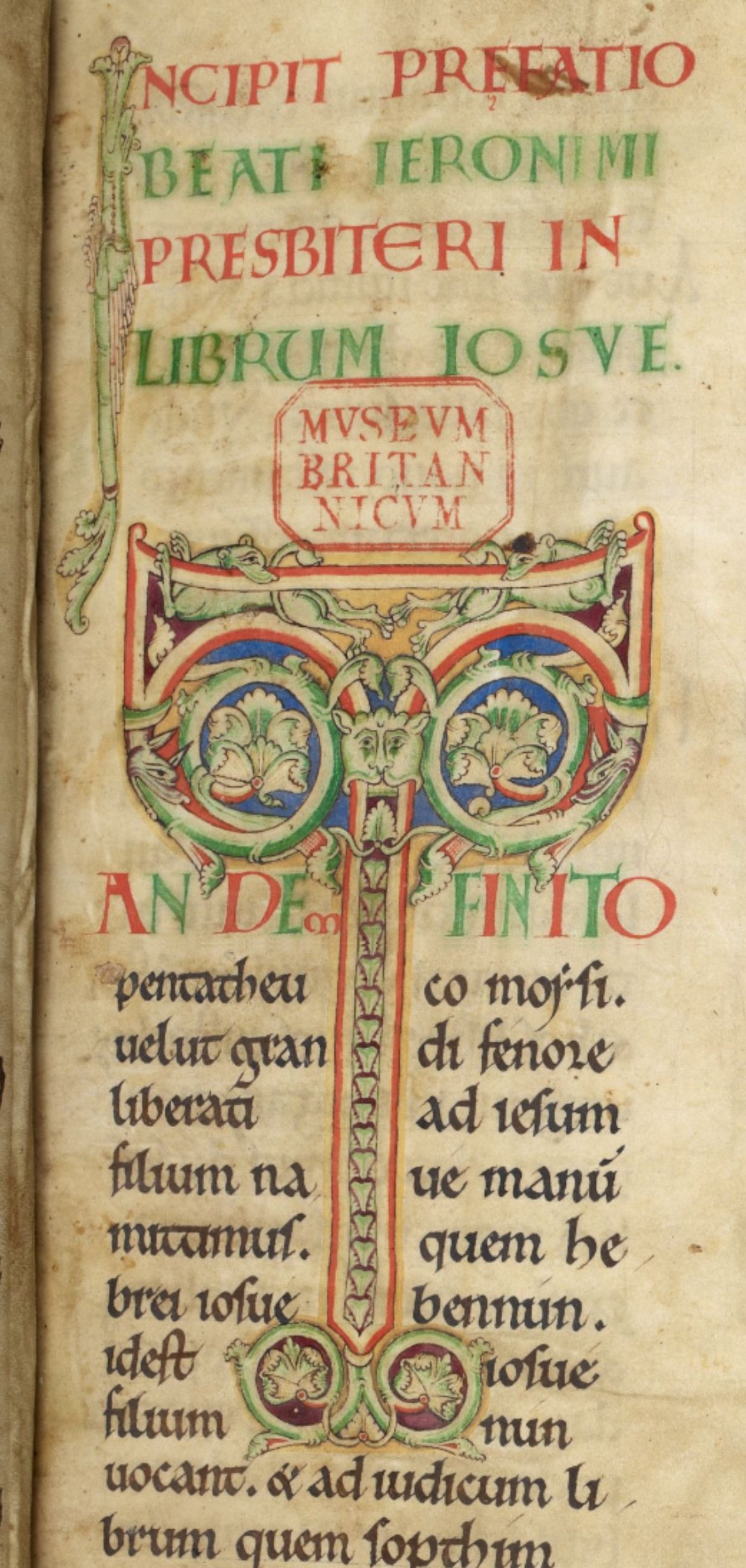

Preface to the Book of Joshua

British Library, Royal MS 1 C VII, folio 1r. Detail of the decorated initials ‘I’ (‘Incipit’) and ‘T’ (‘Tandem’).

The opening page of the manuscript has two decorated initials, both of which incorporate beasts into their designs. In the rubric – the heading – there is the initial ‘I’ of the Latin word ‘Incipit’ (‘Here begins’).

The rubric reads in full:

INCIPIT PREFATIO

BEATI IERONIMI

PRESBITERI IN

LIBRUM IOSVE

Translation:

Here begins the preface of Saint Jerome, the priest, in the book of Joshua

For more on Jerome, see britannica.com/biography/Saint-Jerome.

The ‘I’ is actually a dragon with foliage sprouting out of its mouth and from its tail.

British Library, Royal MS 1 C VII, folio 1r. Detail showing a dragon forming the initial ‘I’ (‘Incipit). Image rotated.

Below the heading, a decorated ‘T’ – the start of the Latin word ‘Tandem’ (‘At last’) – begins Jerome’s preface.

British Library, Royal MS 1 C VII, folio 1r. Detail showing biting dogs and dragon heads, and another beast head.

At the very top of the initial, two running dogs – turning their heads backwards as if eyeing each other up – bite firmly into the bar of the letter. Below, each side, the bar sprouts spiralling foliage emanating from the mouths of what appear to be the heads of two dragons.

Finally, between the dragon heads, another monstrous head spews forth the long vertical line of the ‘T’.

The beasts, here, work as decoration rather than alluding to the content of the text. Moreover, they are unlike the beasts in the Rochester Bestiary which often have complex symbolism and allegorical meaning attached to them.

It is noteworthy that artists working in the centuries before the Conquest of England (in 1066) – including not only manuscript artists but those whose media were metal, stone, bone or ivory – often liked to use biting, intertwining beasts in their decorations. Indeed, these earlier, ‘zoomorphic’ styles continued beyond the Conquest and influenced Anglo-Norman artists, including those who worked on the Rochester Bible.

Capitula for the Book of Joshua

On folio 2 recto, the capitula, or list of chapters, for the book of Joshua is produced. There we find two more decorative initials incorporating beasts.

British Library, Royal MS 1 C VII, folio 2r. Detail showing two decorative initials, ‘I’ (‘Incipiunt’) and ‘P’ (‘Promittit’).

The first beast, top left, is another dragon. It holds its wings closed along its back and it has a ‘bifurcated (forked) and foliate (having leaflike motifs) tail’. It is squeezed inside the initial ‘I’, which begins the Latin word ‘Incipiunt’.

British Library, Royal MS 1 C VII, folio 2v. Detail showing the initial ‘I’ with an inhabiting dragon.

The rubric reads in full:

INCIPIUNT CAPITVLA IN LIBRUM IOSUE

Translation:

‘Here are the chapters in the book of Joshua’

The second beast is a two-headed dragon-like creature, though its heads are reminiscent of those of the dogs, seen above. It forms the vertical stem of the initial ‘P’, the beginning of ‘Promittit’.

The spotted, and rather worm-like, abdomen of this fantastical beast terminates in foliage, which now almost disappears into the gutter of the margin.

Not to be missed are the two human faces gazing out, as if in wonder, from the final leaves of the spiralling vine which sprouts forth from one of the dragon’s mouths to form the ‘bowl’ of the ‘P’. We will see more human faces later.

British Library, Royal MS 1 C VII, folio 2v. Detail showing the initial ‘P’ with double-headed dragon and human faces.

The opening sentence from the ‘P’ reads:

Promittit Dominus Iosue dicens sicut fui cum Moyse ero et tecum.

Translation:

‘The Lord promises Joshua, saying, “As I was with Moses, so will I be with you.”’

Joshua took over the leadership of the Israelites as they entered the promised land, Canaan. Here we read that Joshua was to receive the same level of intimacy and blessings that his predecessor Moses had experienced.

Book of Joshua

British Library, Royal MS 1 C VII, folio 2v. Detail showing the historiated initial ‘E’.

The opening of the book of Joshua begins with the rubric:

INCIPIT LIBER IOSUE

Translation:

‘Here begins the book of Joshua’

It is immediately followed by a colourful initial letter ‘E’ (for ‘Et’, ‘And’). This initial is the first of the Rochester Bible’s historiated ones, letters containing a narrative scene which tell a ‘story’ directly related to the text they accompany. In this case, the ‘E’ provides a mini-narrative concerning Joshua and his forerunner Moses.

As well as the historiated aspect of the initial, we also have two decorative beast heads which support the curved back of the ‘E’ in their mouths.

The text reads:

Et factum est ut post mortem Moysi serui Domini loqueretur Dominus ad Iosue filium Nun ministrum Moysi et dicerit ei…

Translation:

‘Now it came to pass after the death of Moses, the servant of the Lord, that the Lord spoke to Joshua, the son of Nun, the minister of Moses, and said to him…’ (Joshua 1:1)

Moses, depicted on the right with white hair and beard, points to the younger looking Joshua who carries himself in a subservient pose – note the outstretched arms – characteristic of Old Testament figures in earlier English narrative artwork, such as the Old English Illustrated Hexateuch (c.1020-40). Moses hands a book to Joshua; it signifies the transference of the Law that was given to Moses by God on Mount Sinai, and thus also of Joshua's acceptance of the mantle of leadership of the Israelites.

British Library, Royal MS 1 C VII, folio 2v. Detail showing the historiated initial ‘E’. Image has been rotated.

The two men are framed by decorated columned archways, from which the central column forms the middle bar of the ‘E’. Above this middle bar appears the top of a domed tower, which is rather reminiscent of the tower that appears in the historiated initial at the beginning of the cartulary section of Textus Roffensis (folio 119r), and which represents St Andrew’s Priory. There is a good possibility that the Rochester Bible was being worked on soon after the commencement of Textus, so, correspondingly, it is possible that the same monk-artist illustrated both historiated initials.

Judges

The opening of the book of Judges begins with an elegant initial ‘P’, beginning the clause:

Post mortem Iosue consuluerunt filii Israel Dominum

Translation:

‘After the death of Joshua, the children of Israel consulted the Lord’.

British Library, Royal MS 1 C VII, folio 27v. Detail of the initial ‘P’ (‘Post’).

Decorative beasts fill the entirety of the initial. In the ‘bowl’ of the ‘P’, two canines are tangled within a scrolled vine, biting at the inner boundary of the curve, filled with grey-purple acanthus leaves.

When we look closely, this curve becomes the serpentine body of a dragon’s head which bites the upper section of the vertical stem of the ‘P’, narrowly missing the heel of another biting dog situated within the upper compartment of the stem.

British Library, Royal MS 1 C VII, folio 27v. Detail of the initial ‘P’, showing three dogs and a dragon’s head.

British Library, Royal MS 1 C VII, folio 27v. Detail of a dragon.

Below, in the middle compartment of the stem, an orange-red dragon – wings arching forward over its head – sinks its teeth into the stem. As with other dragons in the Rochester Book, its tail sprouts a leaf.

British Library, Royal MS 1 C VII, folio 27v. Detail of a weasel-like dog.

The final compartment of the stem of the ‘P’ houses another biting dog. It shares the long neck of the two canines within the ‘bowl’ of the ‘P’, but it might also be said that its neck contortions give it the air of a weasel!

The statement that ‘the children of Israel consulted the Lord’ is ironic because the book of judges is probably the most disturbing and violent book of the Bible. And from this opening sentence the book of Judges concludes at the end (chapter 21), ‘In those days there was no king in Israel; all the people did what was right in their own eyes.’ Quite plausibly, the endlessly biting animals in the illustration are attacking the vine, which is the word of God.

Reverend Lindsay Llewellyn-MacDuff

Ruth

British Library, Royal MS 1 C VII, folio 52v. Detail of the decorative initial ‘I’.

The book of Ruth opens with a decorative initial ‘I’ (‘In’), inhabited by a pair of green dragons. The sentence that follows reads, ‘In diebus unius iudicis quando iudices pręerant facta est fames in terra’, ‘In the days of the judges, when the judges ruled, there came a famine in the land’ (Ruth 1:1).

These mirroring dragons, when looked at closely, are intricately detailed. Dots run along their bodies from the base of their foliated tails as far as their birdlike wings, which are closed tightly against their backs. The dots then re-emerge along their shoulders and necks, which are ridged with dark green scales. The mouths of the dragons are agape allowing their sharp, protruding tongues to almost touch.

British Library, Royal MS 1 C VII, folio 52v. Detail showing the mirroring dragons. Image rotated.

The book of Ruth is interesting in its contrast to the book of Judges. In the book of Judges everybody is talking about God; in the book of Ruth hardly anybody does. However the book of Judges is an account of the moral collapse of the people of Israel, while the book of Ruth is an account of the faithfulness of a foreign woman: a woman who will be the ancestor of King David and thus of Jesus Christ.

Ruth follows her mother-in-law back to Bethlehem from Moab, after her husband and brother-in-law have both died, leaving her mother-in-law without male kin. Ruth is steadfast in her care for her mother-in-law and is rewarded for her faithfulness, narratively/theologically speaking, by meeting and marrying Boaz. Boaz is a man of honour who is relatively distant kin to Ruth’s dead husband.

Reverend Lindsay Llewellyn-MacDuff

Preface to the Book of Kings

Arguably, the most spectacular of the Rochester Bible’s beasts appears at the beginning of St Jerome’s preface to the Book of Kings on folio 55v. There we see a wonderful dragon whose curving body forms the left side of the ‘bowl’ of the ‘U’ for the Latin word ‘Uiginti’ (‘Twenty’).

British Library, Royal MS 1 C VII, folio 55v. Detail showing the decorated initial ‘U’ (‘Uiginti’) which begins St Jerome’s preface to the Book of Kings.

The dragon’s head, outlined in blue, is, unusually, in semi-profile; and from its mouth protrudes a flame-red tongue. Just to the right, two human faces, perhaps with expressions of awe, peek out from beneath leaves.

Looking like a swan, the dragon arches its back and raises its wings – beautifully painted – and stands on the tips of its clawed toes as if it might suddenly take flight. Alas! Its tail, evolving into a scrolled vine, has become entangled within the frame that finishes the vertical stroke of the ‘U’. Even dragons have their weaknesses.

The text that follows on from the ‘U’ reads ‘Uiginti et duas litteras esse apud Hebre’ ‘Twenty-two letters [of the alphabet] there are among the Hebrews’. Jerome then ruminates on the corresponding twenty-two ‘scrolls’, or books, of the Hebrew Bible (the Old Testament), a discussion that is as meandering as the dragon’s tail, as Reverend Lindsay Llewellyn-MacDuff put it to me!

Readers of modern translations of the Bible may note, here, that these list 39 books, not 22, but we should note that Jerome clumped some books together, such as classing the twelve books of the minor prophets as one book. My thanks once more to Lindsay for this observation.

I Kings

British Library, Royal MS 1 C VII, folio 58r. Detail showing a historiated initial ‘F’ (‘Fuit’).

The book of I Kings – today it is usually titled I Samuel, after the protagonist – opens with a superb historiated initial ‘F’ (‘Fuit’) depicting Elkanah (labelled ‘Helcana’) and his two wives, Anna (or Hannah, who eventually becomes the mother to Samuel) on the left, and Phenenna (labelled ‘Fenenna’) on the right.

The text that follows introduces their story:

‘Fuit vir unus de Ramathaimsophim de monte Ephraim; et nomen eius Helchana […] et habuit duas uxores, nomen uni Anna, et nomen secundę Fenenna. Fueruntque Fenennę filii; Annę non erant liberi.’

Translation:

‘There was a man of Ramathaimsophim, of Mount Ephraim, and his name was Elkanah […] and he had two wives, the name of one was Anna, and the name of the other Phenenna. Phenenna had children, but Anna had no children.’

British Library, Royal MS 1 C VII, folio 58r. Detail showing, from left, Anna, Elkanah and Phenenna with her two children.

The scene is very reminiscent of three Old Testament family ‘portraits’ found in earlier Anglo-Saxon artwork – see the Old English Illustrated Hexateuch, folio 9r – where the parents are shown sitting and one of the children plays with a globe-headed plant his mother is holding. In the Rochester Bible’s historiated ‘F’, Phenenna’s children are playing with red balls, which may be toys or possibly a representation of fruit.

Anglo-Saxon narrative art is famous for its deployment of human gestures (borrowed from the Roman stage), and we should note that Anna is shown with one of these, the hand-to-face gesture signifying grief. Her sadness over her childlessness is profound.

In terms of the beasts present in the ‘F’, we have three splendid ones inhabiting its arborial stem.

British Library, Royal MS 1 C VII, folio 58r. Detail showing a dragon squeezed into the stem of the letter ‘F’. Image is rotated.

At the top, a green and red dragon is squeezed tightly into the stem’s blue compartment, its fine bird-like wings pressing against its worm-like abdomen. Like other dragons in the Rochester Bible, it has a foliate tail; and like the very first dragon on folio 1r, its tongue is replaced with sprouting leaves.

Below the dragon, we have a face-off between two dogs! Their legs dangle outside the stem as if they are trying to run. If we look really closely, we can see that they are fighting over what looks like a ball. Perhaps then its playtime, nothing more.

II Kings

The book of II Kings (aka II Samuel) presents us with another fascinating and beautiful historiated initial, the letter ‘F’ (for ‘Factum’).

British Library, Royal MS 1 C VII, folio 92r. Detail of historiated letter ‘F’ (‘Factum’).

The text that follows reads:

‘Factum est autem postquam mortuus est Saul, ut David reverteretur a cęde Amalech, et maneret in Siceleg dies duos.’

Translation:

‘Now it came to pass, after Saul was dead, that David returned from the slaughter of the Amalekites, and abode two days in Siceleg.’

The story continues: David learns from an Amalekite soldier of the death in battle of King Saul and his son Jonathan – whom David deeply loved. David rips his garments in two at the dreadful news, and on understanding that the Amalekite had answered the fatally wounded Saul’s plea to put him out of his misery, David mercilessly has the Amalekite executed for killing the ‘Lord’s anointed’.

In the historiated ‘F’ we see David, now crowned as king, playing his harp, accompanied by two other musicians, one playing a violin-type instrument, the other a large horn, its size perhaps suggesting the horn of the aurochs – a species of cattle now extinct.

As with the previous historiated ‘F’, beasts inhabit the stem. At the top, a pair of almost identical green-and-red dragons face each other, their long foliate tails curling outside the frame of the stem. Unlike the pair of dragons at the opening of the Book of Ruth, these have no fiery tongues. An uneasy truce, perhaps.

British Library, Royal MS 1 C VII, folio 92r. Detail of a pair of dragons. Image rotated.

Further down the stem, a spectacular pair of birds – possibly representing eagles – raise their wings and intertwine their necks as if in an embrace. Could it be that the artist was hinting at what David had lost at the death of his beloved Jonathan?

British Library, Royal MS 1 C VII, folio 92r. Detail of a pair of birds, possibly eagles. Image rotated.

The final beast in the stem of the ‘F’ is another dog, though its tail resembles that of a lion. Uniquely among the dogs of the Rochester Bible, it chews its own paw. Could this be another signal of David’s loss?

Finally, right at the bottom of the stem, two more human faces, gazing out in wonderment, appear from the scrolled foliage.

British Library, Royal MS 1 C VII, folio 92r. Detail of a dog chewing its own paw and two human faces gazing out of the foliage. Image rotated.

III Kings

British Library, Royal MS 1 C VII, folio 120r. Detail of a decorated initial ‘E’ (‘Et’).

The text of the book of III Kings (aka I Kings) commences with a truly elegant and beautifully painted initial ‘E’, which begins the opening line:

‘Et rex David senuerat, habebatque ętatis plurimos annnos. Cumque operiretur uestibus, non calefiebat.’

Translation:

‘Now King David was old, and advanced in years; and when he was covered with clothes, he was not warm.’ (III Kings 1:1)

Beasts adorn the ‘E’. Pairs of blue, back-to-back dog heads, one at the top, one at the bottom, firmly hold the letter’s curved back with one mouth whilst a profusion of foliage sprouts forth from the other.

Griffins make a dramatic appearance – the only ones to appear in the manuscript.

British Library, Royal MS 1 C VII, folio 120r. Detail of a pair of griffins.

With the hindquarters of a lion and the head and wings of an eagle (though here with less-than-typical rounded ears), the griffin is a majestic beast associated in bestiaries with strength and valour. The two griffins in the Rochester Bible, somewhat heraldic in their confrontational configuration, raise their wings and open their hooked beaks, ready to bite!

The final pair of human faces appear in this decorative initial, again peeking from foliage with mouths agape. What might they mean? Are they a representation of human wonder or the feeling of awe – this is a Bible full of fantastical beasts, after all – or are they just the product of artistic whimsy?

British Library, Royal MS 1 C VII, folio 120r. Detail of a pair of heads within foliage.

Like Joshua, III kings begins with a transition of power. Unlike the orderly transition from Moses to Joshua (which is coordinated by God), however, David is weak (old, in bed, and feeling the cold) and there's a consequential power vacuum. There's also a less evident divine hand on the transition. It's only after a degree of squabbling and scheming among his wives and children, that Bathsheba (she of the rooftop bath) succeeds in levering her young son (Solomon) onto the throne, followed by some positively Game of Thrones-esque score settling.

Reverend Lindsay Llewellyn-MacDuff

IV Kings

British Library, Royal MS 1 C.vii, folio 154v. Detail showing the historiated initial ‘P’.

The beginning of IV Kings (aka II Kings) is marked out by a bold historiated initial ‘P’. It is ‘historiated’ because it tells a story, or narrative. In the ‘bowl’ of the ‘P’ is a depiction of the ascension of Elijah into heaven, the account of which appears later in chapter 2 of IV Kings:

‘And as they went on, walking and talking together, behold, a fiery chariot and fiery horses parted them both asunder: and Elias [Elijah] went up by a whirlwind into heaven.’ (IV Kings 2:11)

This depiction of Elijah in the Rochester Bible has the prophet rising above trees, his chariot drawn by two stallions leaping forth into a stylised, fiery heavens – though perhaps looking more like a rainbow to modern eyes. Additionally, there are three fish under water; this alludes to the river Jordan mentioned in the story (in verse 7).

British Library, Royal MS 1 C.vii, folio 154v. Detail showing the ‘bowl’ of the historiated initial ‘P’.

In medieval Christian teaching, the prophet Elijah foreshadows Christ and thus his ascension prefigures Christ’s own ascension after his resurrection.

Looking at the remainder of the initial ‘P’, we see several beasts that work decoratively, rather than being part of the narrative. At the terminus of the bowl is a creature biting the vertical stem. Curiously, it has mammalian ears but an avian mouth.

Inside the stem, several posturing beasts – along with a human figure – continue the zoomorphic decoration, though arguably they do tell a story of sorts themselves.

British Library, Royal MS 1 C.vii, folio 154v. Detail showing the upper vertical stem of the initial ‘P’.

Working downwards, we first encounter an aggressive beast with the body of a hound but a head more redolent of a dragon. Look at those pointy ears and red, flame-like tongue! It is eye-to-eye with a more docile creature, one with rabbit-like ears and a small rounded tail. Snapping at its heels is another beast, identical to the first. Bad news for the ‘rabbit’!

British Library, Royal MS 1 C.vii, folio 154v. Detail showing the lower vertical stem of the initial ‘P’.

Intriguingly, below the final beast, is a man dressed in a tunic clambering up the foliated stem. He points up to the beasts whilst blowing his horn. This collection of ‘actors’ works rather well as a hunting scene, even if the beasts are not conventionally represented.

Dr Christopher Monk

The Medieval Monk

Further reading

Mary P. Richards, ‘A Decorated Vulgate Set from 12th-Century Rochester, England’, The Journal of the Walters Art Gallery 39 (1981), pp. 59-67.