Sarsen stones

/

Part of the physical and cultural landscape from before Roman occupation, Sarsen stones have been reused and reinterpreted for thousands of years and yet still hold many mysteries.

In 1988 Anneliese Arnold wrote to Rochester’s Eastgate Museum enquiring as to three large stones located around the Precinct. The curator, Joseph C. Taylor, wrote back:

In geology, drift is a name for all sediment (clay, silt, sand, gravel, boulders) transported by glacier. The last glacial period began about 100,000 years ago and lasted until 25,000 years ago. Large boulders would be transported by the ice and were deposited at odds with the surrounding geology. During natural erosion or land clearance by humans these stones were oftem moved to the borders of fields and serving as boundary markers, or were reused within structures. Larger or more curious stones remained fixed features of a landscape evolving over thousands of years.

Today the etymology of sarsen is understood to have originated from the Old English Saracen in the Wiltshire dialect, a common medieval name for Muslims used by extension for anything regarded as Pagan (non-Christian), i.e. part of the pre-existing pagan cultural landscape.

Four sarsens are today located within the Precinct of the Cathedral, with many more around Rochester, Medway and Kent. Two of these have distinctive bulbous forms, almost resembling cartoon clouds in stone or perhaps magma, frozen in time. These are relatively rare for sarsens of the area. The bulbous features are known as concretions; compact masses formed by the precipitation of mineral cement.

The two bulbous stones have recently been moved to either side of the entrance to the Old Deanery garden.

The concretion action is thought to typically occur around fossilized features on the original stone surface, not unlike how an oyster forms a pearl around a grain of sand. Fossil collectors would often break open these features to identify what might lie at their centre.

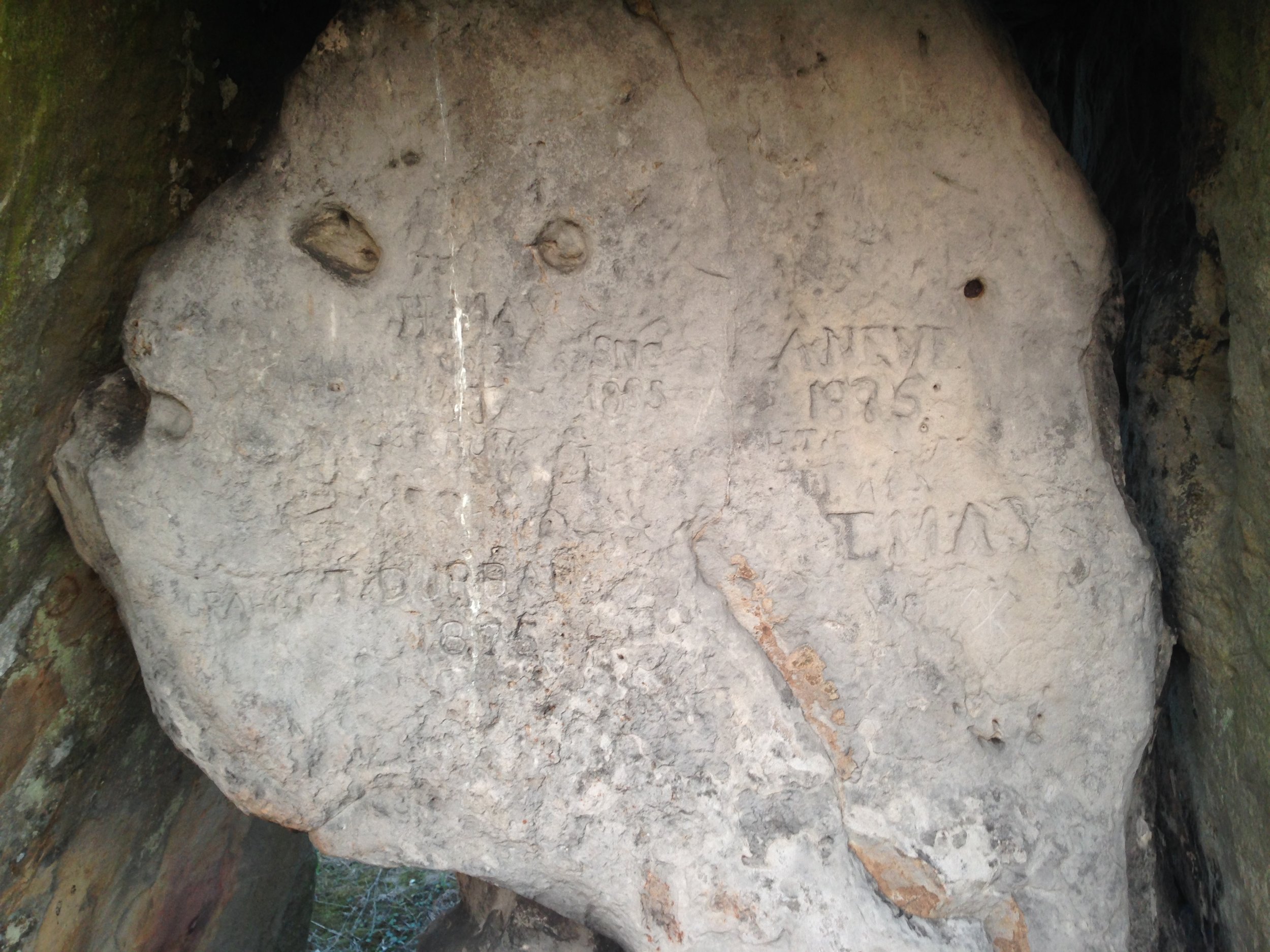

The sarsen stones around Medway reveal the diverse ways these stones have been reused and reinterpreted over thousands of years. Kit's Coty House is a chambered long barrow near the village of Aylesford in the southeastern English county of Kent. Constructed circa 4000 BCE, the stones would originally have formed the entrance to the long barrow which has subsequently eroded away.

Photos of Kit’s Coty House along the Pilgrim’s Way between Aylesford and Bluebell Hill.

Kit’s Coty forms one of the Medway Megaliths, just down the road from the Countless Stones.

3D model of the Countless Stones in close proximity to Kit’s Coty.

The countless stones is a motif that appears in English and Welsh folklore, known from sixteenth century textual sources. As with many of the megaliths, miniature stories are encoded within their names, sometimes outlasting their original sense and even language. The third of the most well-known Medway Megaliths is the White Horse Stone.

The White Horse Stone, Bluebell Hill.

The white horse of Kent is the old symbol for the Jutish Kingdom of Kent, dating from the 6th–8th century. The white horse relates to the emblem of Horsa, the brother of Hengest, who according to legend defeated the King Vortigern near Aylesford. Nineteenth-century antiquarians speculating that the Lower White Horse Stone may have taken its name from the White Horse of Kent, which they in turn believed was the flag of the legendary fifth-century Anglo-Saxon warriors Hengest and Horsa, though this has since been discredited. Instead the story behind the name appears to be forgotten, at least for now.

A large Sarsen boulder was discovered used within the foundations of the Early Norman Cathedral, during the underpinning works that also discovered the foundations of Ethelberhts Cathedral of 604 AD (Livett 1889). The stone was removed ‘and now resides in my garden’, wrote Livett (1889, ). This is thought to be the large boulder now situated at the entrance to King’s Orchard.

Cross-section drawing of the West Facade wall foundations near the north-west doorway, showing a large sarsen boulder reused in the Early Norman foundation. Livett 1888.

Interaction with the stones at the sarsen stones at the Cathedral, both on a social and spiritual level, has continued through the twentieth century. On 24th July 1940 a large Sarsen was transported to the Cathedral from Wateringbury. The stone was sited in the north-west corner of the Cloister Garth where it remains today, though the circumstances around it’s transportation requires further investigation.

Photographs of the sarsen in the cloisters transported from Wateringbury. Rochester Cathedral Chapter Library, Lapidarium Portifolio, Anneliese Arnold 1990.

Reinterpretation and engagement with sarsens and megaliths continues today. Solstice events at Stonehenge have become extremely popular, and new projects under development with the National Health Service are using visits to the stones as part of rehabilitation projects for sufferers of long-term mental health issues. Today the Medway Megaliths are part of this reinterpretation, some largely forgotten and abused, some remaining key parts of the landscape physically and culturally. Kit’s Coty and the Countless stones are Historic England sites and waypoints on the popular pilgrimage and hiking route the Pilgrim’s Way. Our stones have become key features of the Cathedral Gardens, each with their own stories to tell, to be retold and reimagined for many more years.

Jacob Scott

Heritage Officer