The reliquary annex, c. 1100

/The reliquary annex

c. 1100

December 18, 2021

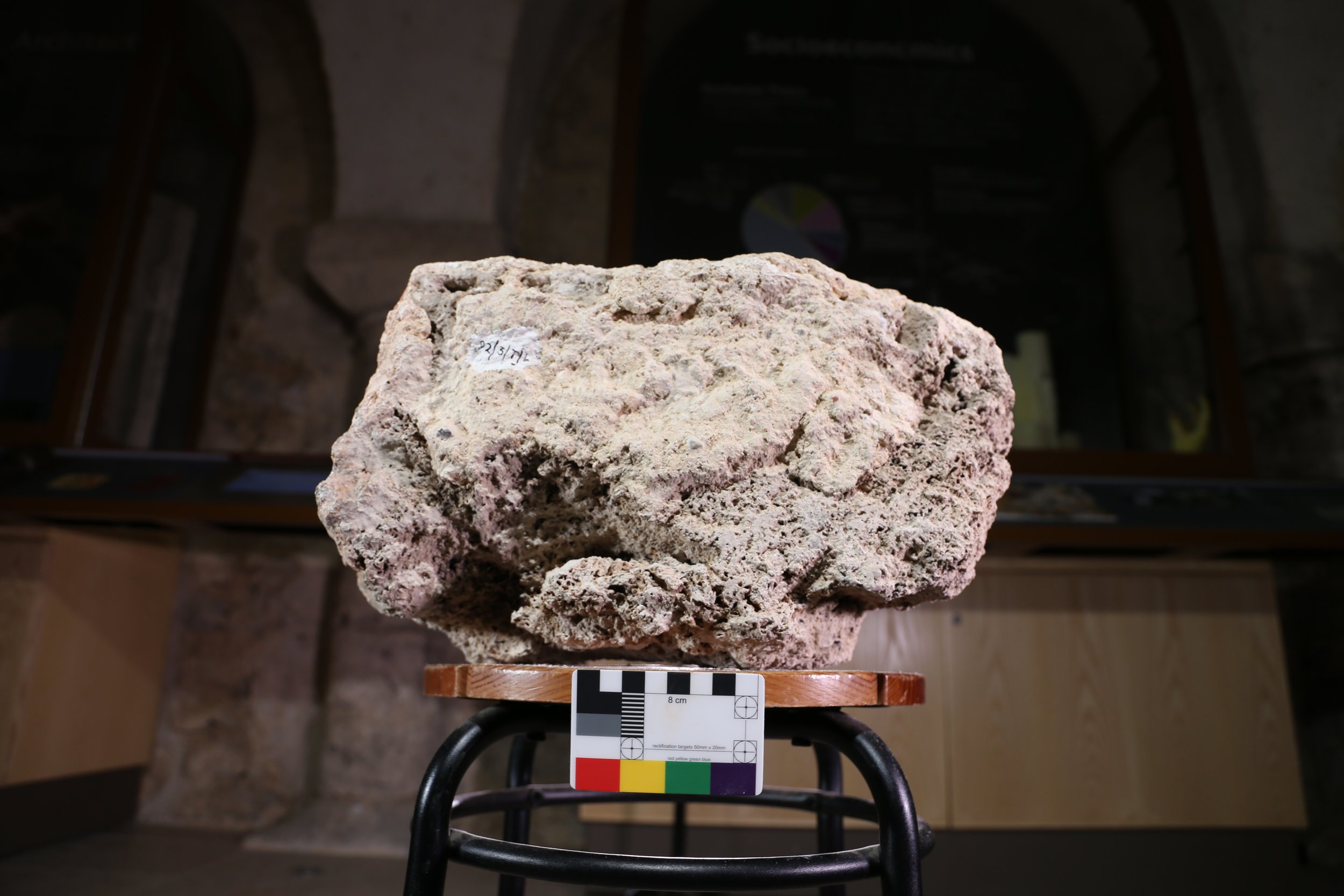

Three plastered tufa stones, one depicting the shoulders of a Bishop with a halo possibly originated from a small annex on the east of the building proposed to be a reliquary for the bones of these two saints.

Gundulf’s cathedral established the basic floor plan of the western portion of the cathedral as it survives today. However, the extensive redecoration after the 1137 fire and the rebuilding and extension of the east end after another fire in 1179 have obliterated or obscured many features of Gundulf’s original structure. The eastern portion of the crypt, now the Crypt Exhibition Area, and the plain arcade of the south side of the nave is believed to survive from this time, providing a glimpse into a plastered Tufa Stone structure with rounded Romanesque arches, tympana and vaulting.

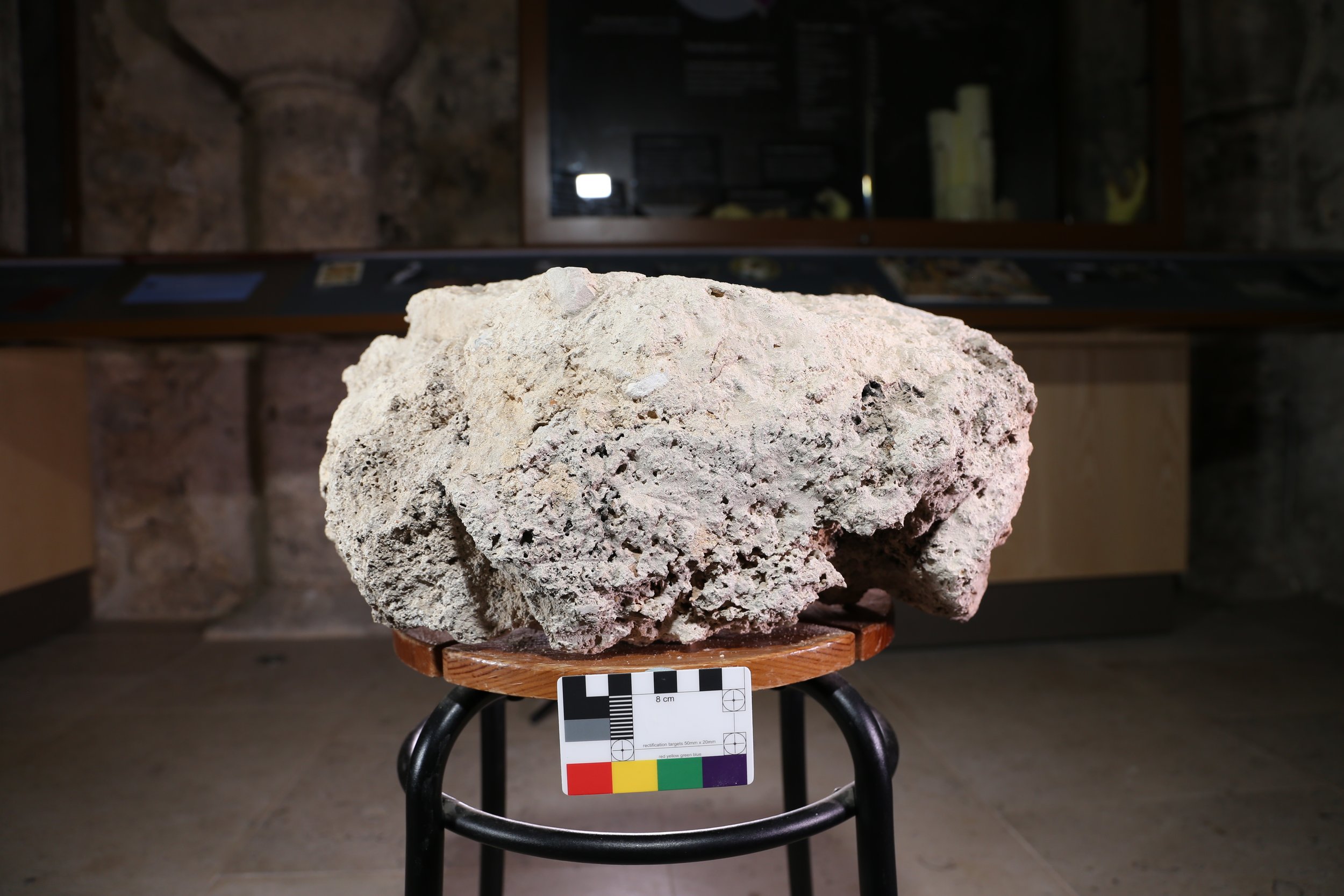

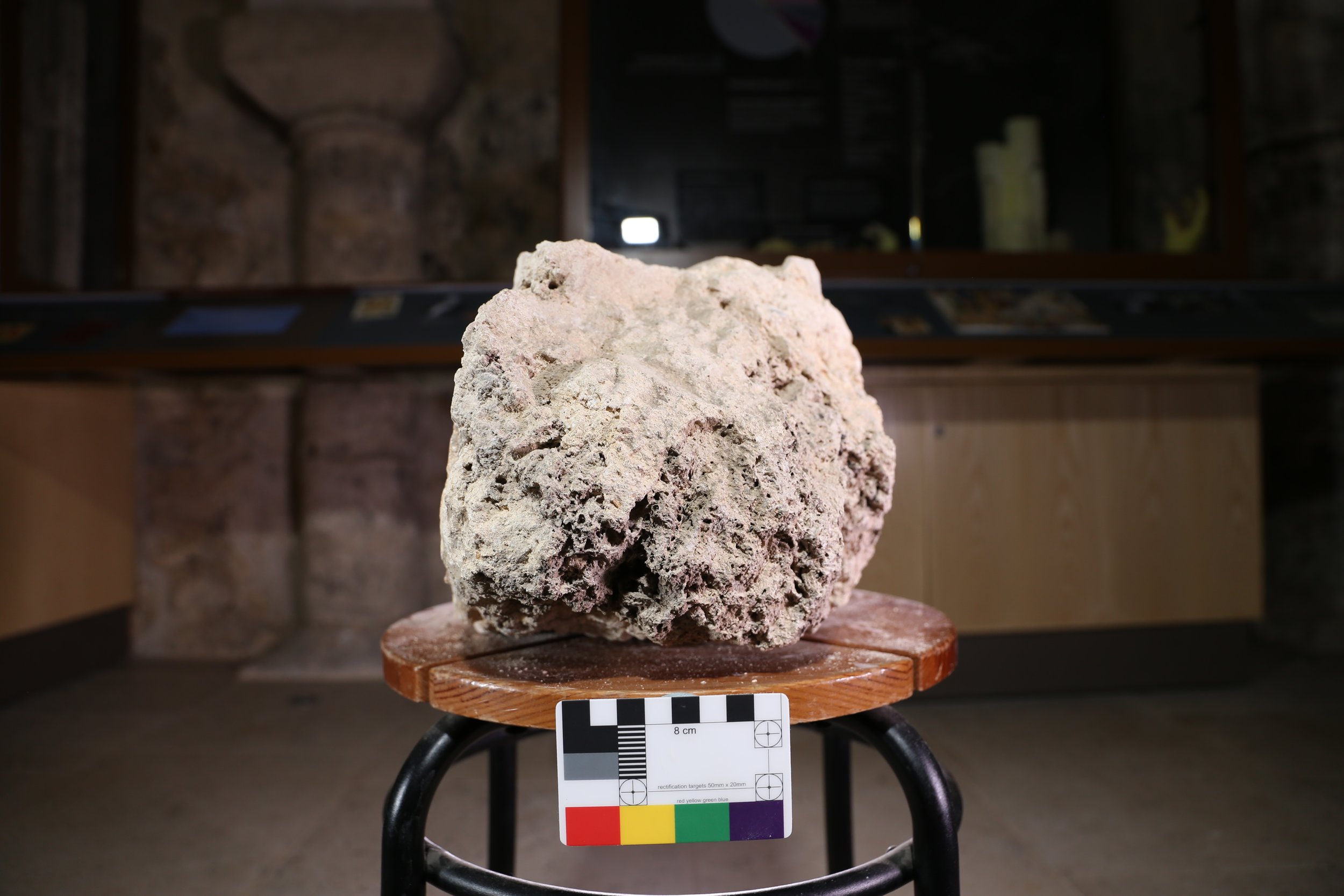

Just three items within the Lapidarium collection have been ascribed a provenance in Gundulf’s cathedral. Fragments PL-1, PL-2 and PL-3 are plastered tufa stone, two with vividly painted decoration surviving.

The fragments were recovered by the Perry Lithgow Partnership reused in the vaulting of the Ithamar Chapel (the easternmost portion of the crypt).

A general understanding of the form of Gundulf’s crypt from the surviving westernmost bays, the evidence from probing and excavations and spolia establish both a floor plan of the space and indicate the forms of the architectural superstructure. The provenance of PL-1 and PL-2 within the Cathedral is unidentifiable from internal evidence, although the unburnt nature of all three suggests they originate from crypt-level rather than the ground floor or the first floor of the east end which would surely reveal smoke darkening.

PL-3 is a voussoir featuring the head and shoulders of a bishop with a halo. At this early date, it likely represents either Bishop Paulinus or Ithamar. The plaster has preserved the arc segment remarkably well, indicating an arch circumference of over one metre. The surviving windows in the north and south walls of the easternmost crypt bays are smaller. This is similar in size to the archways forming the north and south arcades of the crypt but the voussoirs do not match PL-3, being larger in profile. Assuming the eastern bays of the crypt matched the surviving portions of the north and south walls, only one arch is identified within the established architectural-historical model as a possible candidate for provenance - that into a small eastern annexe off the centre bay theorised to have functioned as a reliquary for Paulinus and Ithamar after their translation from the c.604 cathedral around the turn of the twelfth century (St John Hope 1898).

Excavations in the area by St John Hope and during 2014 recovered bones and timber proposed by St John Hope as being buried after the Dissolution, although the finds recovered in 2014 were not radiocarbon dated or radioisotope tested before reinterment.

Tentatively ascribing a provenance for PL-3 in the eastern annexe of Gundulf’s crypt allows us to draw in two of the few other artefacts dated to Gundulf’s time. Dendrochronological dating of a portion of a door in the North Quire Transept established a date in the early C12th (Edwards 2014).

Miles and Tatton-Brown (2002) propose that such a fine door, featuring ironwork in the form of St Andrew’s saltire cross, would most likely have a prominent position within the building. Its survival indicates this was unlikely to have been at ground level, affected by the fire, and perhaps also originates by the entrance to the eastern annexe from the crypt.

That so few items within the Lapidarium collection are ascribed to this period may be a result of the limited understanding of stone materials employed in the late-twelfth century at the site, and it has been noted by various authors (for example, West 1996) that fine Caen grotesques from the west façade may have seen reuse in the mid-twelfth century. Gundulf’s cathedral, consisting largely of Tufa stone and with comparatively few sculptural details, would be less represented in a corpus retained for the finesse of its sculpture. Topographic circumstances have undoubtedly played a role as well, with plaster less resistant to handling and damage during the two successive medieval fires than finished stone surfaces.

Jacob Scott

Research Guild