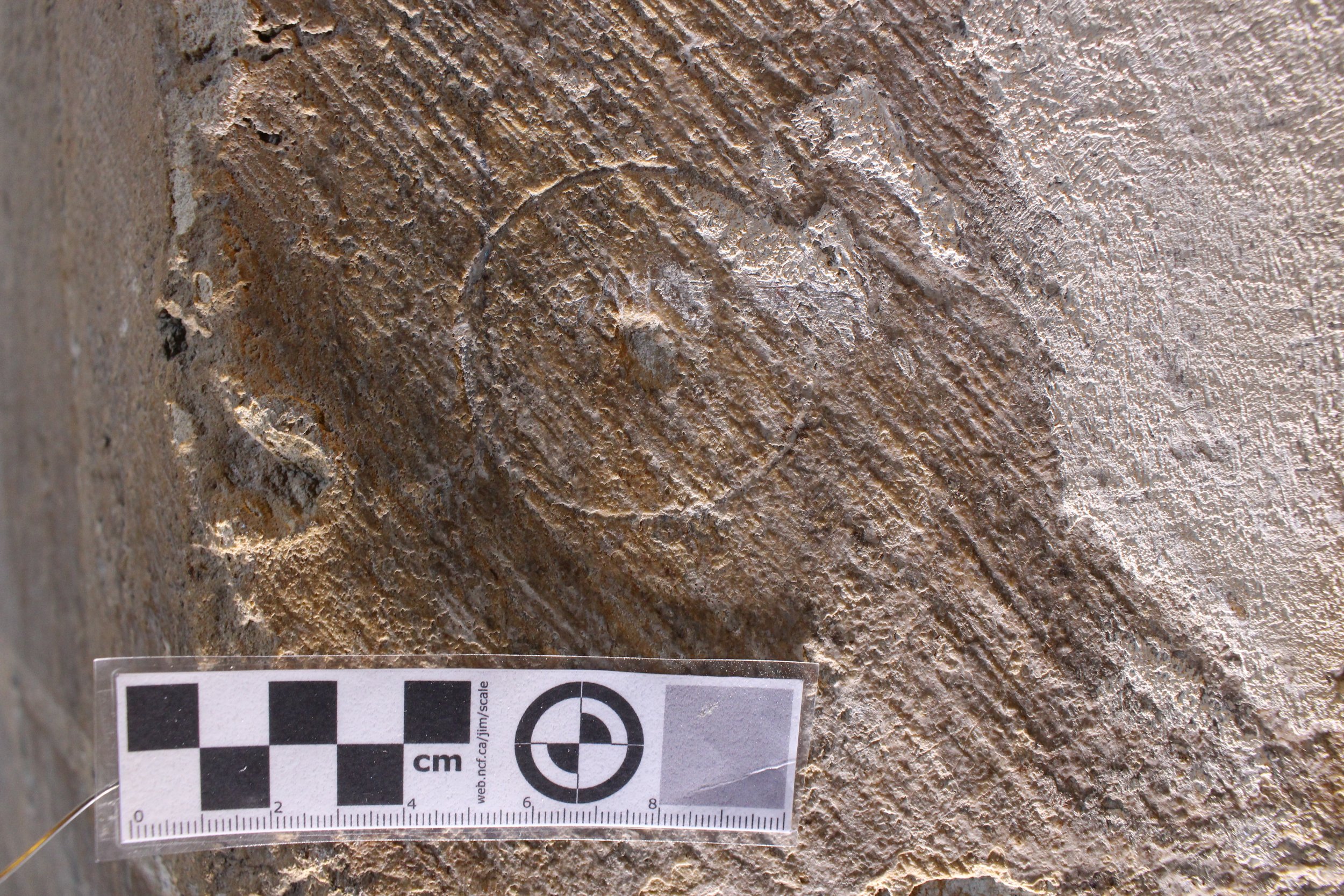

Circle and multifoil graffiti

/

Circle and multifoil graffiti

September 27, 2021

The most common form of graffiti throughout Europe are those variously described as daisy wheels, hexafoil, or witches marks.

The data from Rochester Cathedral, as at many other sites, shows that none of these terms are appropriate to describe the entirety of these designs. Curvilinear graffiti occurs in enough numbers that clustering occurs around spiritually significant areas of the building. Both simple and complex designs appear across all spaces, confounding typological analysis by cluster. The large number of examples seems to support Champion’s suggestions that these resulted from tools similar to small sheers, more common than compasses in the middle ages (Champion 2015a, 39). This multi-purpose tool hung at the waist and was broadly analogous to a modern pocket-knife.

Typology of curvilinear graffiti.

A typology is presented. A small collection of marks at high level must have been left by the masons, probably before construction. A significant portion of all curvilinear graffiti comprises a single circle, often with a visible mark at the centre. Here the word ‘multifoil’ refers to all designs more complex than those composed of individual arcs or single circles. Concentric designs of varying complexity also occur in some number. Occasional examples include those divided irregularly. Occasional examples of repeated and deeply inscribed circle designs created at kneeling height support a repetitive ritualised created, while others have a more meandering form. Many quatrefoil designs are recorded, also sexfoil and several more complex multifoil designs. Almost all are undated, although one inscription by a G H dated 1777 occurs within a simple concentric border in the south quire transept eastern aisle and an irregular elaborate design occurs overlying a date of 2nd December 1782, possibly by an ‘I S’.

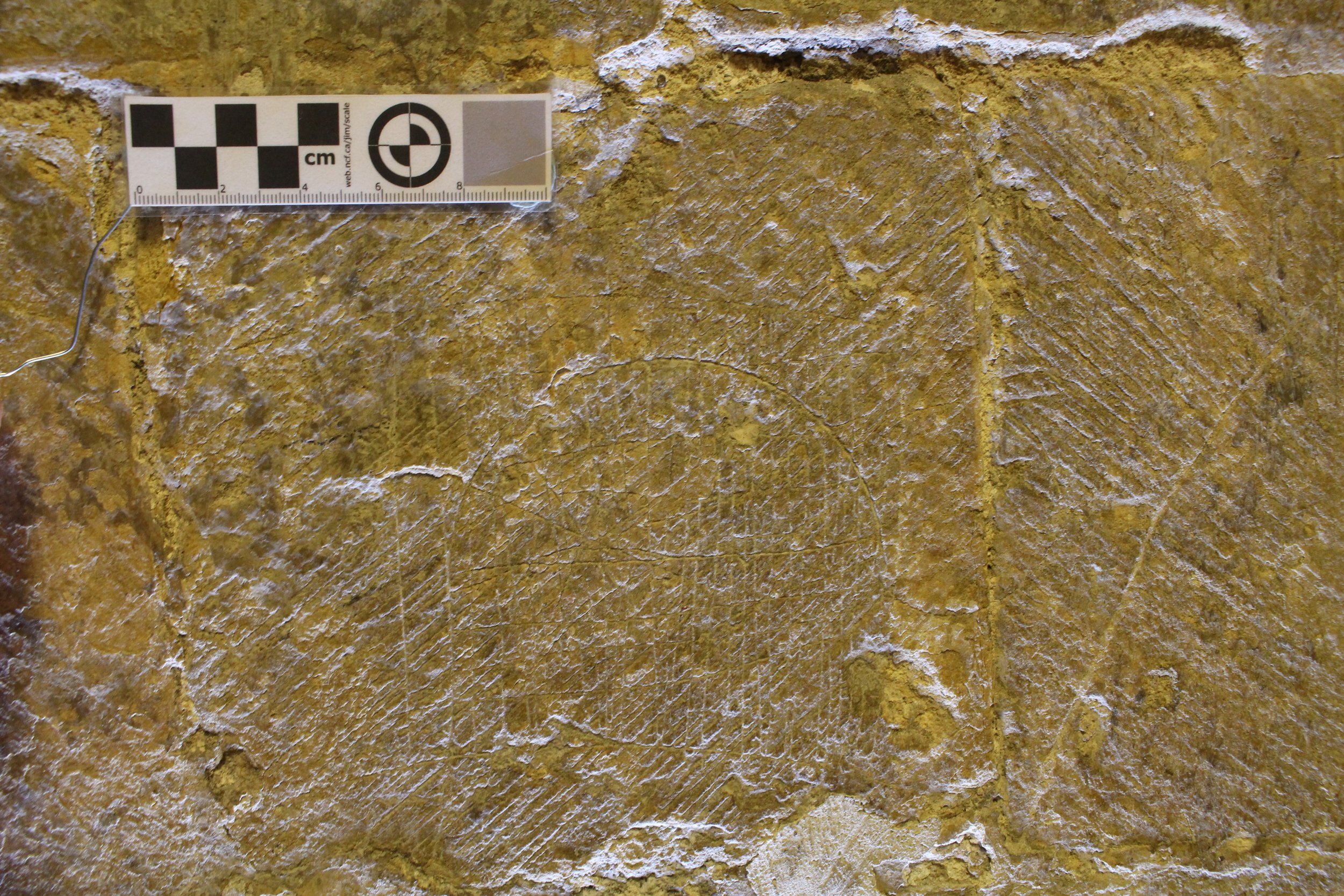

Unique examples of curvilinear graffiti.

Multifoil graffiti are sometimes interpreted as Marian symbology. If so, the 178 examples are significant evidence of Marian devotion at the cathedral. Many of these designs occur within Early Modern graffiti clusters but only one or two within the Lady Chapel, constructed in the 1490s.

The distribution of curvilinear graffiti clusters is discussed, although a critical approach is required in identifying such clusters. An affinity is explored with a possible cobweb-inspired graffito and several flower graffiti scattered around the nave. One design occurs in association with a rectilinear matrix interpreted at other sites as offering a spiritual reinforcement to apotropaic properties.

Clustering

This survey has identified four clusters of curvilinear graffiti. Some 30 curvilinear graffiti occur on the nave piers, with many occurring singularly and without proximity to any known feature. Most are at kneeling height. A small cluster of 30 designs occurs close to the later site of the altar to St Nicholas, between the easternmost nave piers. The altar and rood screen were moved here c.1240 from around two bays further west (St John Hope 1898, 215).

A dense cluster of curvilinear graffiti occurs on and around the westernmost pier in the south nave arcade. In contrast to all other clusters of this form identified within the building, many of these graffiti occur at a standing height. The radii of these designs are much larger than those in other clusters at Rochester. Perhaps its focus was of a different nature than those of others, or they resulted from different tools. Interpreting the source for this cluster is complicated by the Bishop’s consistory court residing at the west end of the south nave aisle from 1681 (Holbrooke 1994, 23) until 1742 (Holbrooke 1994, 114), when it was moved to within the Lady Chapel until removal in the nineteenth century. Seventeenth and eighteenth-century consistory courts dealt largely with matrimonial and probate cases. An interesting avenue of investigation would be whether curvilinear or other apotropaic graffiti exist around the known sites of other early modern consistory courts and thus whether such cases were of an emotionally charged nature. Another consideration is the large painting of St Christopher on the north face of the westernmost pier dating to the late thirteenth-century. A popular saint for pilgrims and worshippers, paintings of St Christopher survive near to the west doors of many cathedrals and churches. A glance through a doorway in passing was thought to protect an individual, particularly travellers, against sudden death throughout that day. However, the majority of the curvilinear graffiti is on the south-west face rather than below the St Christopher on the north face. A final challenge in interpreting this cluster is an apparent custom of inscribing graffiti on the westmost pier of the south nave arcade in other churches and cathedrals. As the majority of this cluster occurs on the south-east face of the octagonal pier, the source for this graffiti was perhaps something located in the westernmost bay in the south nave aisle. This was the approximate location of the medieval and Early Modern font. An affinity with baptism is explored in the next section.

Elaborate curvilinear design, above and possibly in association with symbols and what may be the fragmentary remains of a horned imp or demon.

The shrine to William of Perth existed in the north quire transept from the mid-thirteenth century until the Reformation. Eighteen curvilinear graffiti occur within the vicinity, with a small cluster on the wide pier at the east. It may be that this cluster is associated instead with the chancel of John de Sheppey, although the shrine is known to be one of the major draws for pilgrims. The walls of the eastern aisle of the transept are heavily whitewashed, preventing further investigation. No other pictorial designs, symbols or text occur within the vicinity. The average height of the arcs, circles and

multifoil from the modern floor of the quire, not thought to differ significantly from the medieval level in this location, is 124cm, in contrast to most other designs created from a kneeling position. The majority of curvilinear graffiti in this cluster occur above the stone bench surrounding the pier. Perhaps then this cluster was created by seated individuals, or else is avoiding the stone below the seat which is of a harder material and more difficult to inscribe.

St John Hope identifies the possible site of a medieval altar to St Peter in the east aisle of the south quire transept (St John Hope 1898, 300). This area has a relatively dispersed collection of curvilinear designs. Those on the west face of the square crossing pier are under a thin layer of whitewash. The altar would have resided here from the creation of the east end until the Reformation, before being variously reinstated and removed since the rekindled interest in the medieval layout of the building in later centuries. Although yet to be fully recorded and deciphered, there is also a cluster of whitewashed inscribed calligraphic script, presumed to consist mostly of names, and several bordered inscriptions nearby. No pictorial graffiti occur in the vicinity.

Another challenging cluster to interpret is that on the east wall of the south quire aisle, where it has not yet been possible to identify any recorded altar or other feature. Undated names that are paleographically possibly of a medieval origin occur amongst the cluster of multifoil. Most graffiti in this cluster occurs at kneeling height. Close by, a small circle resides on the easternmost post of the painted oak screens. The screens date to the thirteenth century (Tracy and Hewett 1995, 17).

Apotropaics

Curvilinear designs comprise the majority of abstract graffiti recorded in many churches and cathedrals. At other sites, they occur around fireplaces, in roof spaces, in medieval tithe barns, and around the entrances to caves. Champion describes an observed relationship between apparently apotropaic curvilinear graffiti and fonts (2015a, 39-42). Apotropaic symbols are those created for warding off evil spirits and bad luck. Baptism in the middle ages was a removal of original sin and malign spirits. Some churches still leave the north door of the church open during baptismal ceremonies for venting such entities (Champion 2015a, 41). Curvilinear designs would then serve as a means of protection from these spirits, serving as broadly analogous to Native American dream catchers. The entity is attracted to the design and is captured within. Two curvilinear designs occur on either side of the north nave transept door. A fragmentary curvilinear design occurs outside the door that led into the west end of the north nave aisle, blocked sometime in the eighteenth or early nineteenth century. Underpinning of this area in 1875 revealed the foundations of a Perpendicular porch, thought to date after the construction of St Nicholas church in 1423 (Holbrooke 1994, 124, DRc/Emf/77/7). A curvilinear graffito within the south nave arcade cluster is crossed by many rectilinear incisions, also identified over a VV symbol, the spiritual significance of which is discussed. At other sites, such marks are interpreted as a reinforcing of protection against anything trapped within. However, the form and context of many of these designs, dating over several centuries, are myriad. It does not seem appropriate to describe those designs occurring around altars and shrines as apotropaic. This author has come to refer to these designs colloquially as ‘worry marks’.

The photographic graffiti survey at Rochester Cathedral begun in 2016 has recorded over 7,000 inscriptions from the 12th to the 21st century.