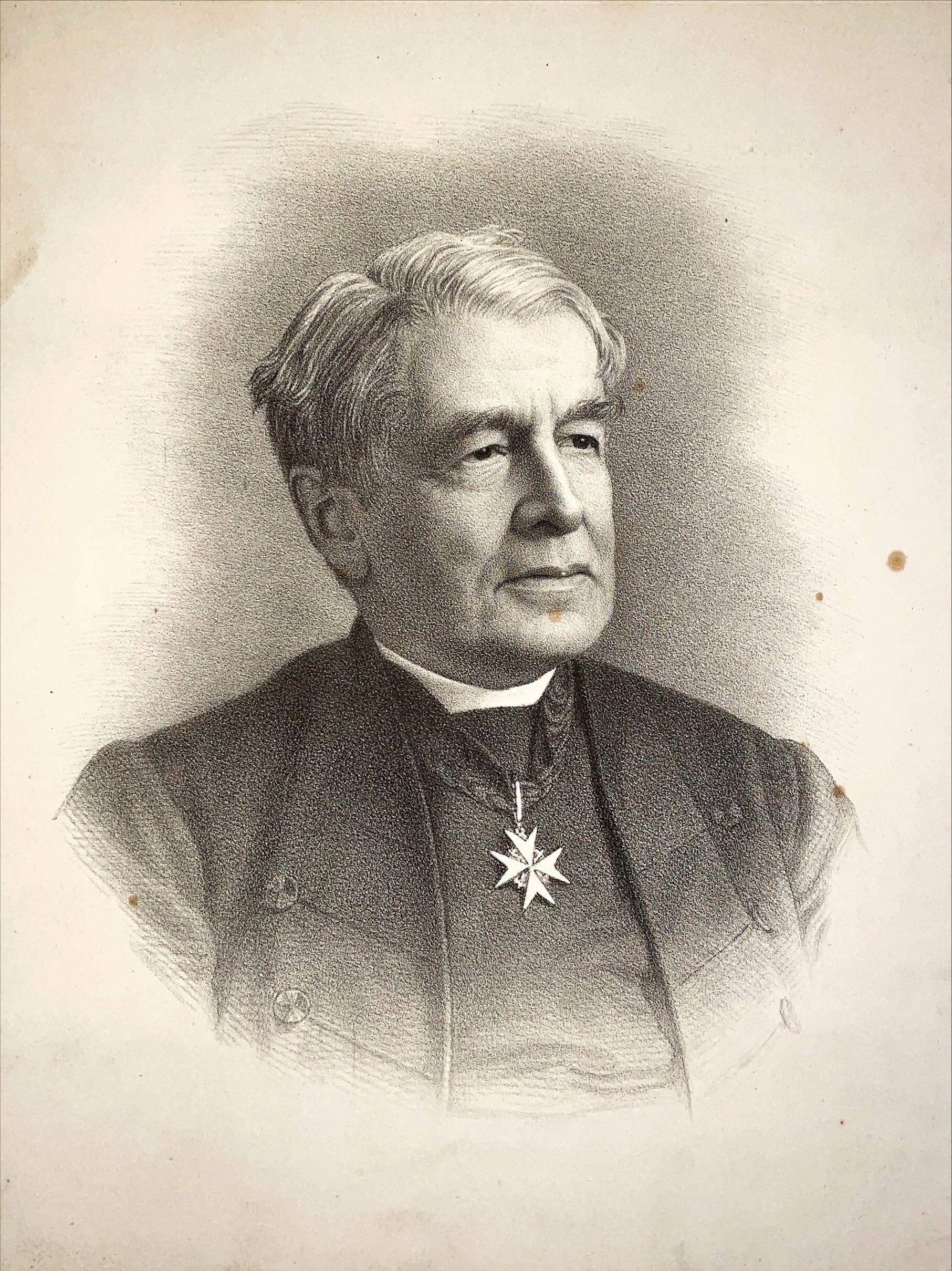

Dean Reynolds Hole (1819-1904)

/

Dean Reynolds Hole (1819-1904)

October 8, 2021

Dean of Rochester Philip Hesketh introduces the life and work of Samuel Reynolds Hole, Dean of Rochester 1887–1904, a celebrated gardener notable for his expertise with roses.

The small village of Caunton in Nottinghamshire is the ancestral home of the Hole family. The Rev’d Hugh Hole is recorded as being the Vicar of St Andrew's, Caunton in 1537. Samuel Hole (father to Reynolds) and his younger brother, Richard, made their fortune in Manchester amongst 'those dark satanic mills' and, with their new-found wealth, bought Caunton Manor. In 1819 Samuel and his family returned to Caunton with three-month-old Reynolds and his two older sisters.

Reynolds was raised at the manor house, which was widely known as a 'House of Sport'. It was here that he developed his love for all things outdoors and rural; hunting, shooting, archery, cricket and particularly his passion for gardening. His earliest memories were of skating on the pond, searching for birds eggs and fishing in the Caunton Beck. This rural haven provided the background to the first sixty eight years of his life.

The art of manliness

Reynolds Hole attended Mrs Gilby's preparatory school near Newark. Sixty years later, when he became Dean of Rochester, he was surprised to discover that his new bishop, Dr Thorold, had also attended the very same school a few years before him. Unlike other boys from a similar background, Reynolds Hole was not sent away to one of the more notable boarding schools, but to Magnus Grammar School in Newark. Although this may not have brought him into direct contact with the spirit of reform abroad in some of the public schools, he nevertheless made good academic progress and further developed his love of sport and country pursuits, relishing every opportunity to return home in order to take part in the local Hunt.

The word 'manly' is rarely encountered today, yet at one time it was part of a common vocabulary, with manliness being seen as almost a cardinal virtue and a particularly English one. This aspiration for all things manly was encouraged by the public schools and by the end of the 19th century had become associated with a particular understanding of the Christian faith which became known as 'muscular Christianity'.

Muscular Christianity was the backbone of the British Empire. The phrase used to describe it was, 'the Englishman going through the world with rifle in one hand and Bible in the other'. This was a world where young men were brought up as Christians, but ready to fight for their beliefs. They were set to rule an Empire built on high moral principles. They were expected to obey orders and enforce rules because they were on the side of right and goodness. Their creed was 'fear God, and walk 1000 miles in 1000 hours'. There was a moral value in tough walking and all forms of hardship.

Games, especially, became the natural metaphor for Victorian moralists. Life was compared to a game watched over by the heavenly Great Scorer and to sin was to take one's eye off the ball. Reynolds Hole is a perfect example of a kind of Christianity common amongst Victorian and Edwardian clergymen and of a general attitude prevalent among the middle class echelons of society, who saw the outbreak of war in 1914, not only in terms of duty and service, but as an exciting game to be played. The historian Noel Annan wrote that the generation of the Great War was assured that 'victory would be ours, because having learnt to play up, face fast bowling on a bumpy pitch and in a blinding light, our men would face bullets and shells without flinching'. This attitude is clearly demonstrated in Sir Henry Newbolt's famous and rose-tinted poem Vitai Lampada, written in 1892:

There's a breathless hush in the Close tonight -

Ten to make and the match to win - A bumping pitch and a blinding light, An hour to play and the last man in.

And it's not for the sake of the ribboned coat, Or the selfish hope of a season's fame,

But his Captain's hand on his shoulder smote -

Play up! play up! and play the game!'

The sand of the Desert is sodden red -

Red with the wreck of a square that broke; - The Gatling's jammed and the Colonel's dead.

And the regiment's blind with dust and smoke.

The river of death has brimmed its banks, And England's far, and Honour a name,

But the voice of a schoolboy rallies the ranks:

'Play up! play up! and play the game!'

Thomas Arnold (1795-1842), the reforming educationalist and headmaster of Rugby. believed that education and religion were but two sides of the same coin, designed to lead to moral perfection. Godliness and good learning were inextricably linked and schools were never mere teaching academies. Education was worthless without the leaven of religion. Bishop Christopher Wordsworth (1807-85), a disciple of Arnold and former headmaster of Harrow, admired by Reynolds Hole, once asked a chaplain of Winchester College, 'What is a college without a chapel?' The chaplain replied, 'An angel without wings'. Arnold's reforms of the I830's were an attempt to instil in schools a spiritual zeal and a love of learning, so turning what he believed were 'dens of thieves' into 'temples of God'.

Manliness was notoriously difficult to define. Whereas Arnold and the early Victorians, looking back to S. T. Coleridge, had seen manliness as putting away childish things and attaining one's potential in living a higher, better and more useful life through learning, others, like Charles Kingsley and Thomas Hughes, later came to equate manliness with robust energy, spirited courage and physical vitality. Thomas Hughes was a pupil of Arnold and attributed to him the belief that sport could build character and create discipline. Yet, in fact, Arnold had little interest in sport and said nothing about it in his lifetime. The philosophy of sport and organised games emerged some fifteen years after his death with the publication of Hughes' novel Tom Brown's Schooldays in 1857. It was a massive success and ran to 50 editions by 1890. The Times commented that it was a book 'every English father might well wish to see in the hands of his son' For school boys this novel became the model of boyish excellence.

In Tom Brown's Schooldays, Hughes depicts his hero Tom as the paragon of manliness; a boy 'frank, hearty, and good natured....chock-full of life and spirits'. Increasingly the masculine and muscular connotations of the word were stressed and it found its converse in effeminacy or any show of weakness and sentimentality. Here were the origins of the 'stiff upper lip' and the advocacy of the cold shower. Hughes gave a series of sermons on 'The Manliness of Christ' and onenly preached muscular Christianity until his deatn in 1895. It was a kind of salvation by sport.

Despite Hughes' novel being set at Rugby under Arnold's headmastership, this understanding of manliness was a long way from Arnold's original intentions. What had been the ideals of godliness and good learning had, by the late 1860's, given way to the cult of organised games and the doctrine of muscular Christianity.

Increasing stress was placed on the salutary benefits of playing games, especially rugby football and cricket, which now became compulsory as part of the school curriculum. Physical activity and high spirits were far more attractive qualities in a boy than classical studies, piety and spiritual zeal. Alongside this development went the establishment of Rifle Corps and cadet groups in which boys were taught to drill, to shoot, to go on manoeuvres and ultimately to command and lead. Somewhat ironically, instead of good learning being linked to godliness it became increasingly associated with agnosticism as the century wore on.

Reynolds Hole was schooled in the early part of the 19th century and lived through this transition in the understanding of manliness. Whilst an ardent admirer of perhaps Arnold's greatest disciple, Archbishop Edward White Benson, Reynolds Hole nevertheless was committed to the doctrine of 'physical activity' and believed it should be encouraged as a source of moral improvement. Reynolds Hole was described by the diarist Henry Silver as, 'a big manly clean-shaven young parson of the Muscular Christianity order. Good at cricket and cross country'. Hole was typical of the robust, energetic and jolly parson so much loved by the Victorians.

Oxford, Ordination, and sporting 'Squarson'

The obligatory European Grand Tour preceded Reynold Hole's matriculation from Brasenose College, Oxford, in 1840. Chasing the fox, to which he was devoted, occupied much of his time and money at university, although he was not unaffected by the religious revival within the Church of England which was centre around Oxford known as the Oxford Movement. Reynolds Hole was inspired by the preaching of Pusey and Newman and he took the decision to be ordained and was appointed curate of St Andrew's, Caunton in 1844. On the death of the incumbent and his father he was made both Squire and Vicar. He then spent many decades lovingly restoring and renovating the church, planting roses along its exterior walls.

All things coming up roses

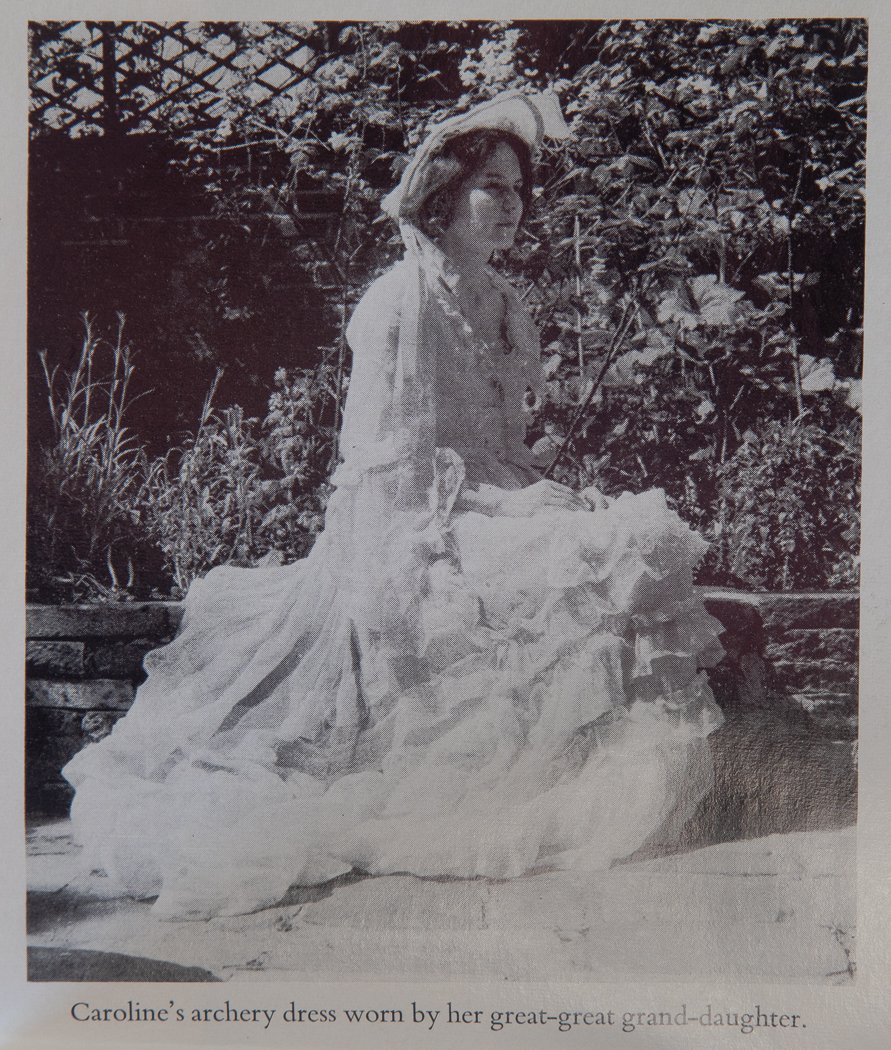

Reynolds Hole was a member of The Royal Sherwood Archers, regularly taking part in events. It was on one such occasion that he met his future wife, Caroline Franklin of Gonalston. Twenty years his junior, Caroline was not only an accomplished archer she was also a keen and able gardener, according to Gertrude Jekyll. Reynolds, a hopeless romantic, who was 'always falling in love' married Caroline in 1861. They had one son, Hugh, who later fought in the Boer War.

His great passion for roses began one day in early April when he received a note from a mechanic in Nottingham, inviting him to assist in judging an Easter Monday rose exhibition organised by local working men.

Though he had a large garden, Hole was not a rose grower, yet and knew little about them. His first thought was that he was the victim of an April’s Fool hoax. Nevertheless, he took up invitation and in a small upper room in a pub found the most wonderful blooms in bottles of various sizes that had been grown under glass. From this moment his love of roses bloomed, and he quickly turned him into a horticultural celebrity. Alfred, Lord Tennyson, the then poet laureate, went as far as addressing him in letters as 'The Rose King'. It also cemented the close relationship and admiration Hole felt for the working man and his committed to improving their situation.

With his new-found fame Reynolds Hole inaugurated the first Grand National Rose Show at St. James Hall, London in 1858. Later, in 1876, along with others he founded the National Rose Society, dedicated to the cultivation and appreciation of roses. His most famous publication, a Book About Roses, ran into over ten editions, was translated into other, languages and became a best seller.

Reynolds Hole was a prolific author and letter writer, and his works can be found in the Cathedral’s Library collection.

Preacher, Orator and Innovator

Reynolds Hole was an inspiring and popular preacher in demand all over the country. He was referred to as the 'Dickens of the Pulpit’, with whom he was well acquainted. Renowned for his ability to appeal to the working masses, he was noted for his humour and directness, once receiving over 400 invitations to preach in one week.

Reynolds Hole preached at St. Paul's Cathedral on 50 occasions with the comment that there was standing room only. His regular evening sermons at Rochester filled the nave with up to 1,000 people. He once held a service for cyclists (the new popular pastime) which was regarded as scandalous.

Reynolds Hole was the friend of both literary and famous giants and was elected a member of the Garrick Club sponsored by his great friends John Leech and William Makepeace Thackeray. He was the only parson invited to the famous Punch table lunches.

Rochester and its gardens

At the spritely age of 68 Reynolds Hole was appointed Dean of Rochester, then a busy industrial city with cement works along the river Medway and a naval dockyard at Chatham. The acrid smell of lime was inescapable and so work soon began on a new garden to 'perfume the air'. His gardening friends admired and advised – most notably William Robinson, Gertrude Jekyll, William Paul, Canons Ellacombe and D'Ombrain.

The eighteenth-century Deanery, residence of Dean Reynolds Hole during his tenure, set within the ‘Old Deanery Garden’.

The gardens at Rochester became famous and received a special mention in Jeykll's Some English Gardens. They magnificent herbaceous borders were painted by the noted English watercolourists, George Samuel Elgood and Arthur Rowe.

Photographs and portraits of Dean Hole, Rochester Cathedral Chapter Library, photographs and portraits collection.

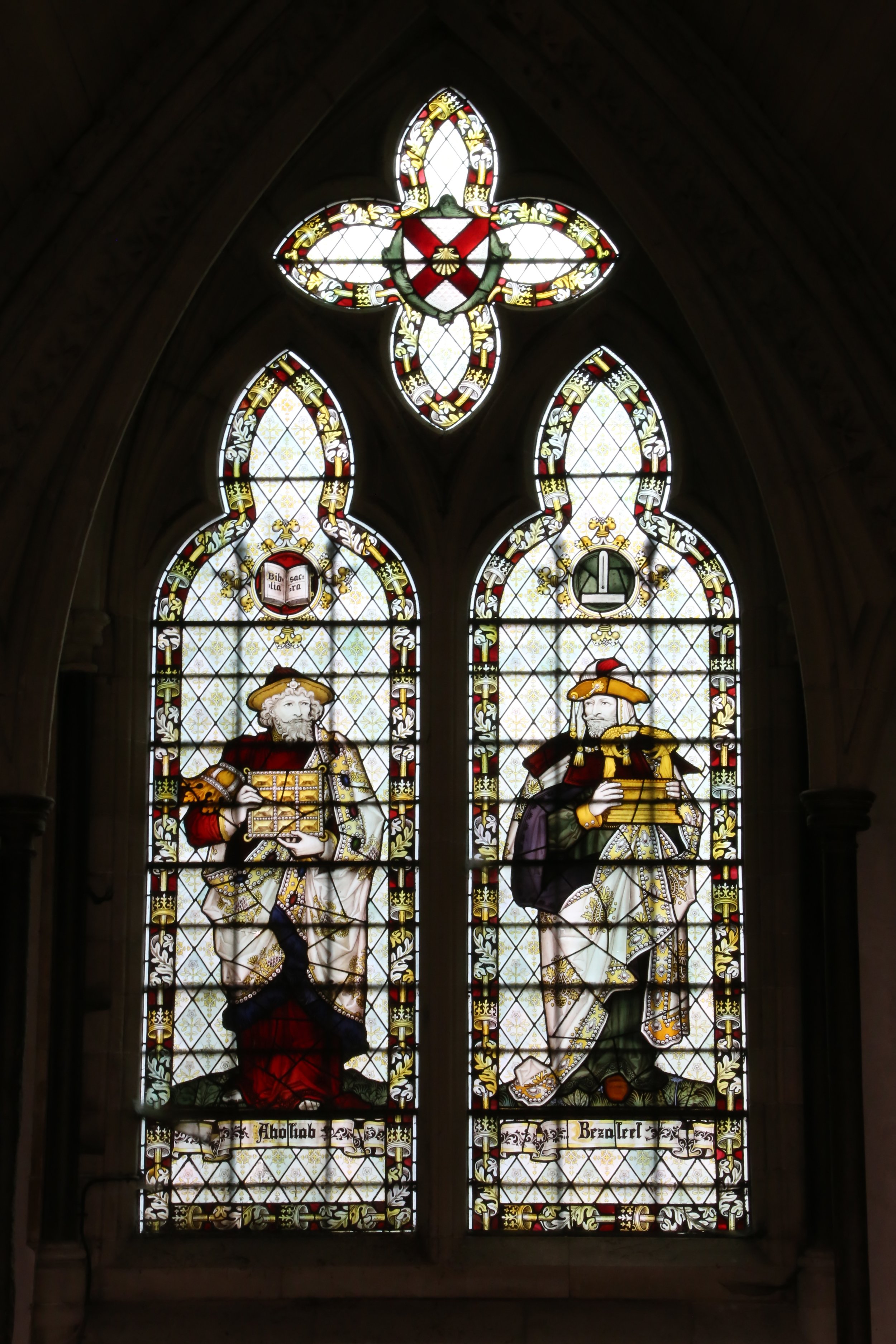

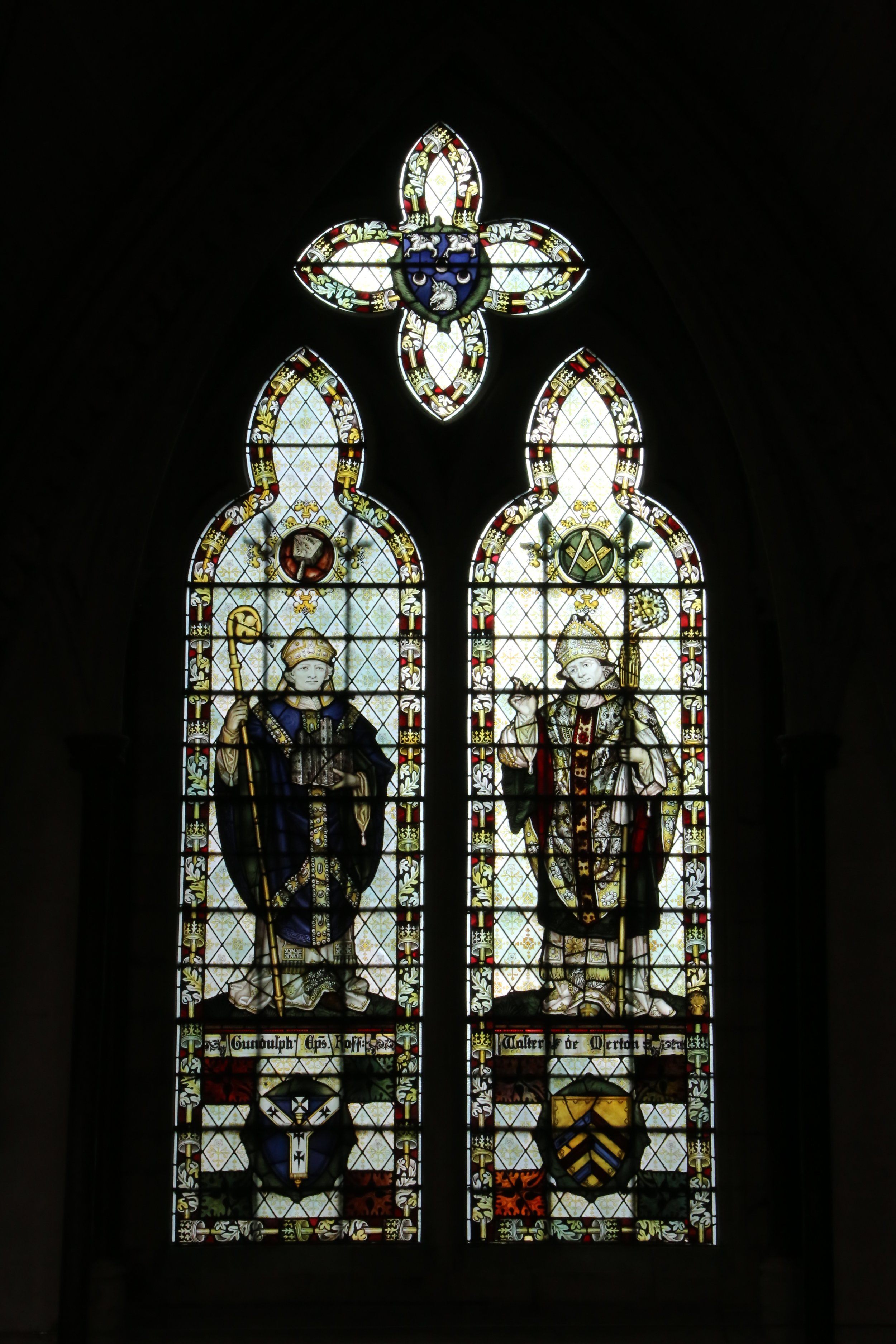

Stained glass windows featuring Aholiab, Bezalel, King Solomon, King Ethelbert, Bishop Gundulf, and Bishop Walter de Merton, south nave transept east wall, by Kempe, 1899. A plaque on the wall records this window and others were given by the Freemasons in commemoration of Dean Hole's appointment to a Grand Chaplaincy in the Grand Lodge of England. They were dedicated on St Andrew's Day 1899.

The Dean of Rochester on a mission

At the age of 75 Reynolds Hole toured America in an attempt to raise money for the Cathedral. Received enthusiastically, he was the guest of many horticulturists and botanists who knew of his fame.

Although disappointed that he had only raised £500, this money was nonetheless essential in urgent restoration work and restoring of the Cathedral Spire to its medieval status. Sadly, Reynolds Hole did not live to see the Spire completed and died aged 85 at the Deanery on 27th August 1904.

In 1874 rose grower William Paul produced cultivar 'Reynolds Hole', described as a 'crimson beauty'. In 1897 Dickson produced a cultivar named 'Dean Hole' in the Dean’s honour.

A giant of his time

From the Deanery at Rochester, Reynolds Hole kept up a constant stream of humorous and charming letter-writing and welcoming quests. Throughout, his life he remained an extremely popular national figure and, on the occasion of his last birthday, received over 100 correspondences, including one from the cabmen at London's Waterloo Station.

Although an impressive monument was commissioned for the south presbytery of the Cathedral, Dean Reynolds Hole was buried in his ancestral home of Caunton in the parish churchyard. The funeral was conducted by Canon Jelf, who had ministered to him in his dying days. At a special Chapter held on 30 August 1904 it was recorded 'We, the Canons assembled in Chapter desire to put on record our deep sense of loss we have sustained in the passing away of our reverend Dean Samuel Reynolds Hole. Endeared to us by his genial disposition and his kindness of heart'.

A man 6ft 3in tall, Reynolds Hole towered over his century as one of the great Victorians of his age.

Dean Philip Hesketh

The Deanery