History of the Lapidarium

/Sculptural fragments revealed by excavations and works over the 19th century were the genesis of the Lapidarium collection today.

The Cathedral is noted as having fared poorly during 18th-century rebuilding campaigns and over the course of the century many areas fell into ruin or were replaced with anachronistic forms, such as the north tower of the west façade and the crossing tower. Three major restoration and redesign campaigns occurred over the nineteenth-century, works under Lewis Nockall Cottingham occuring from 1825 to 1830, Sir George Gilbert Scott from 1871 to 1877 and James L. Pearson from 1888 to 1894. Cottingham was responsible for much internal rearrangement of the Cathedral, some subsequently replaced by Sir Gilbert Scott’s characteristic heavy-handed restorations. Cottingham’s work in particular resulted in the genesis of much of the Lapidarium collection as it has existed for 200 years in several settings.

Much of Gilbert Scott’s exposed work at roof-level was starting to decay by the end of the twentieth century and the piecemeal replacements of pinnacles of coping has resulted in many of the stones catalogued by this study but not added to the Lapidarium collection. Pearson’s restoration of the west façade was generally sympathetic, although notes from this time preserved in the Chapter archives and early photographs of the west façade show many Romanesque mouldings and sculptural forms were illegible before this time.

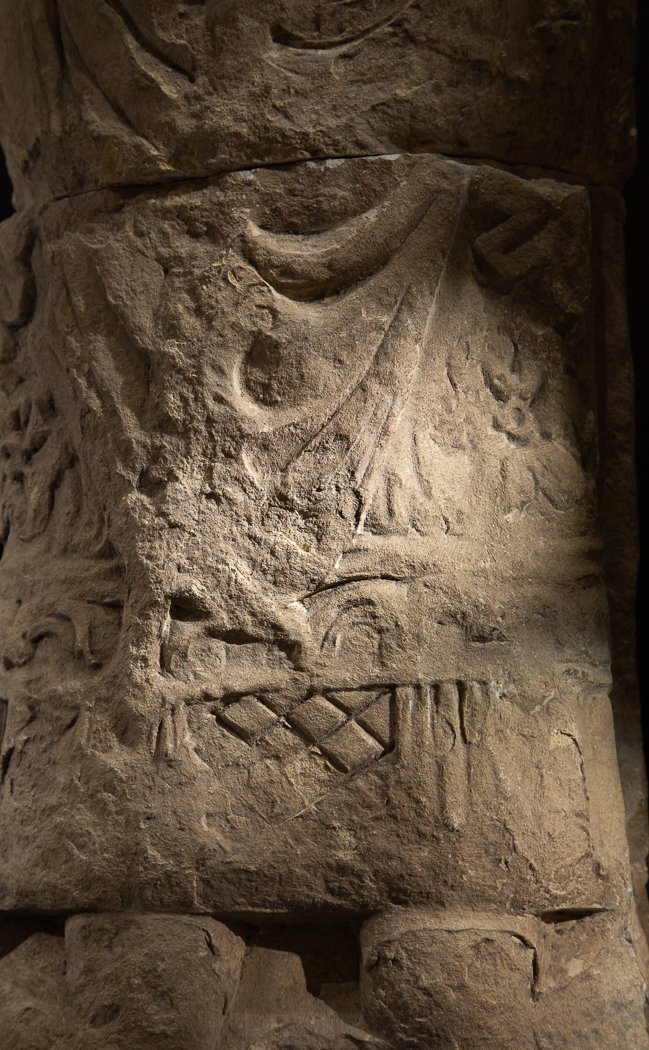

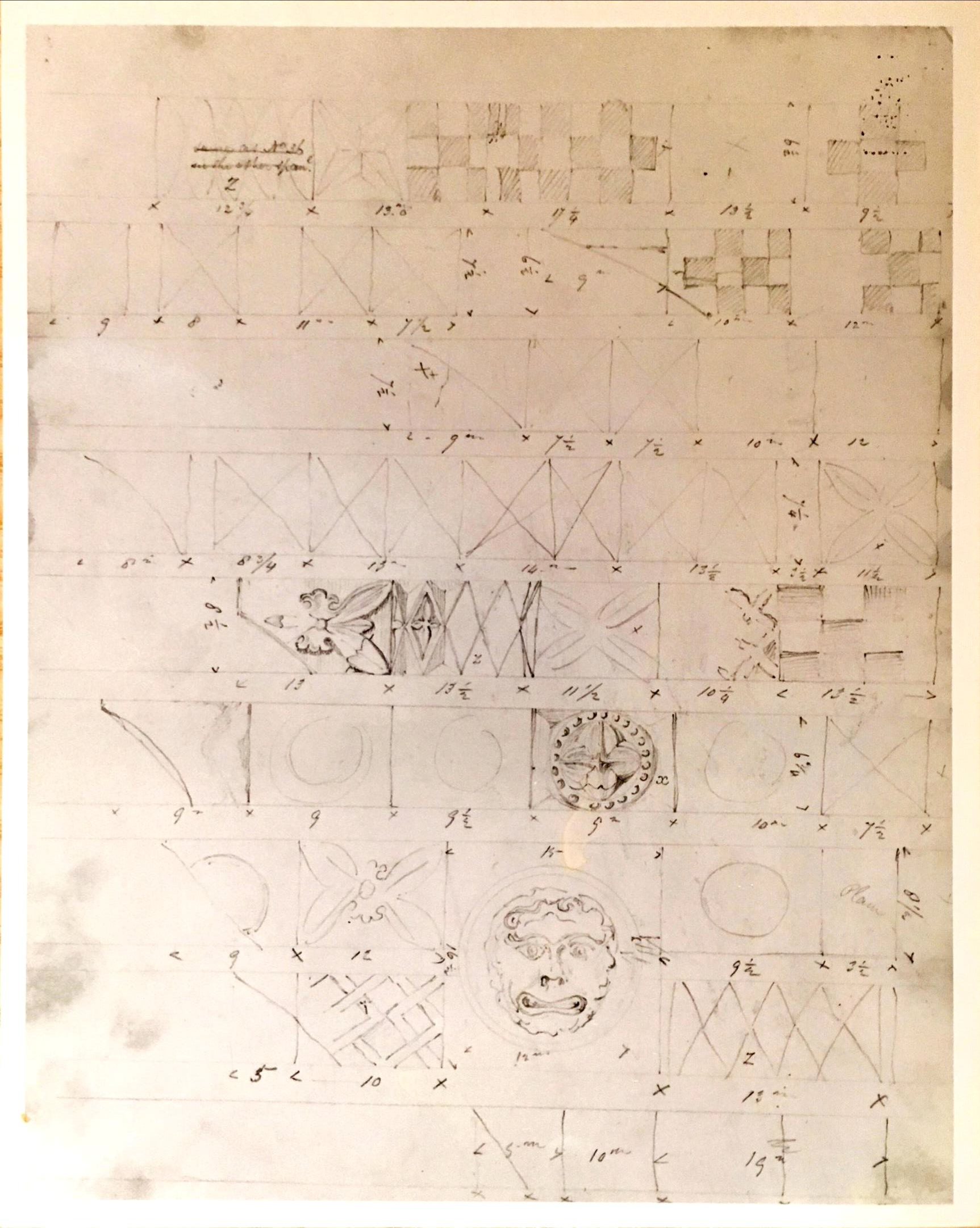

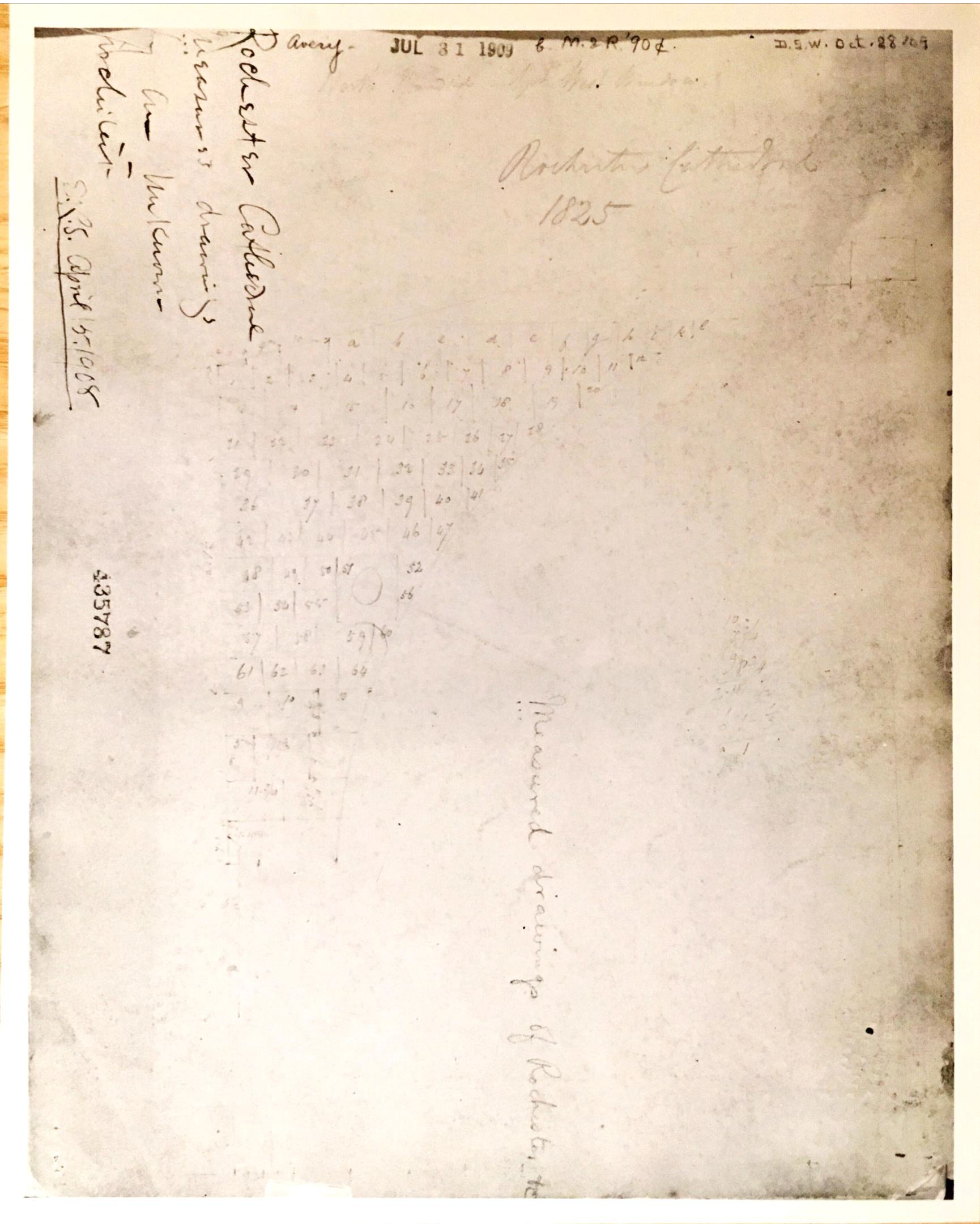

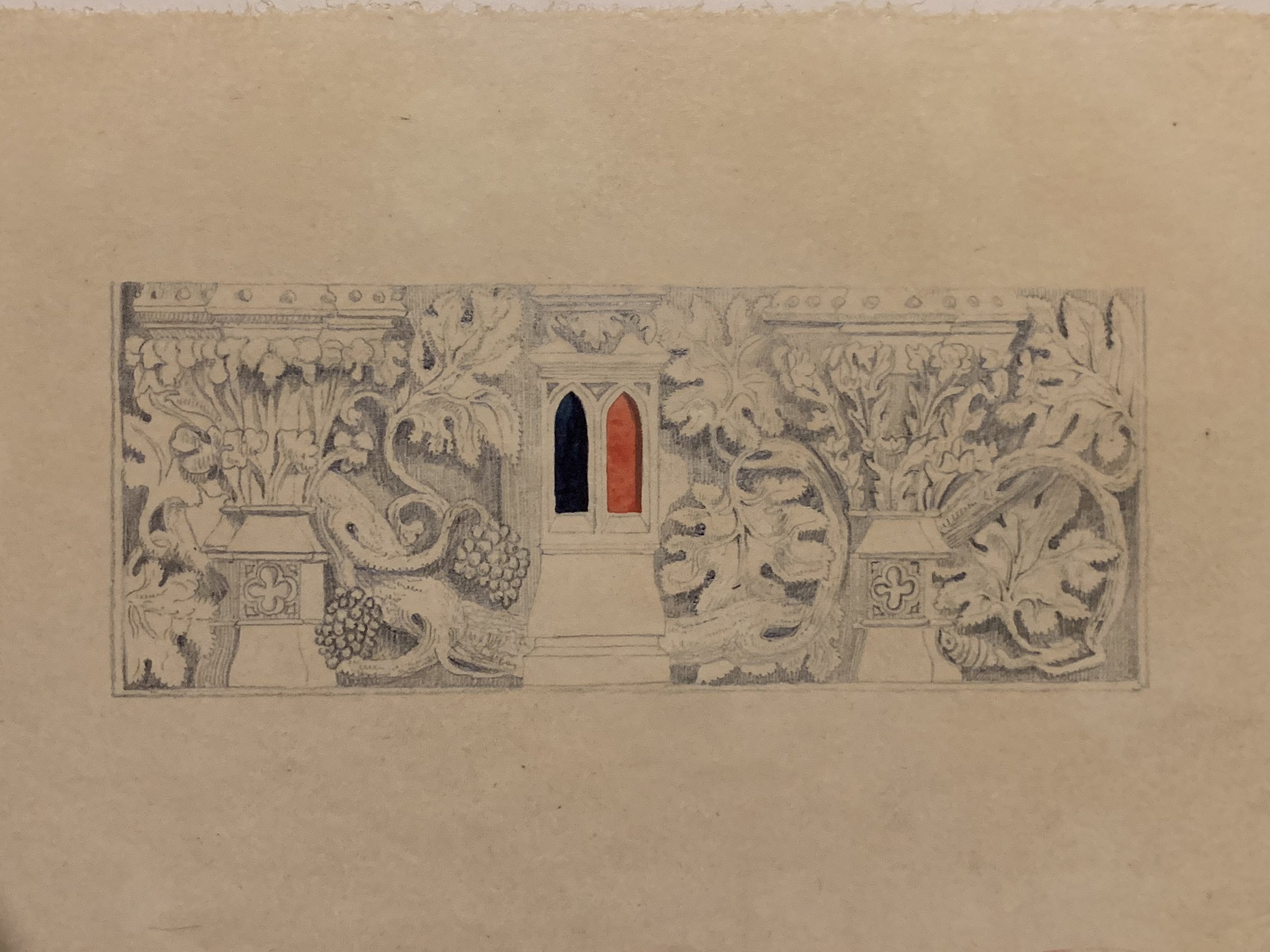

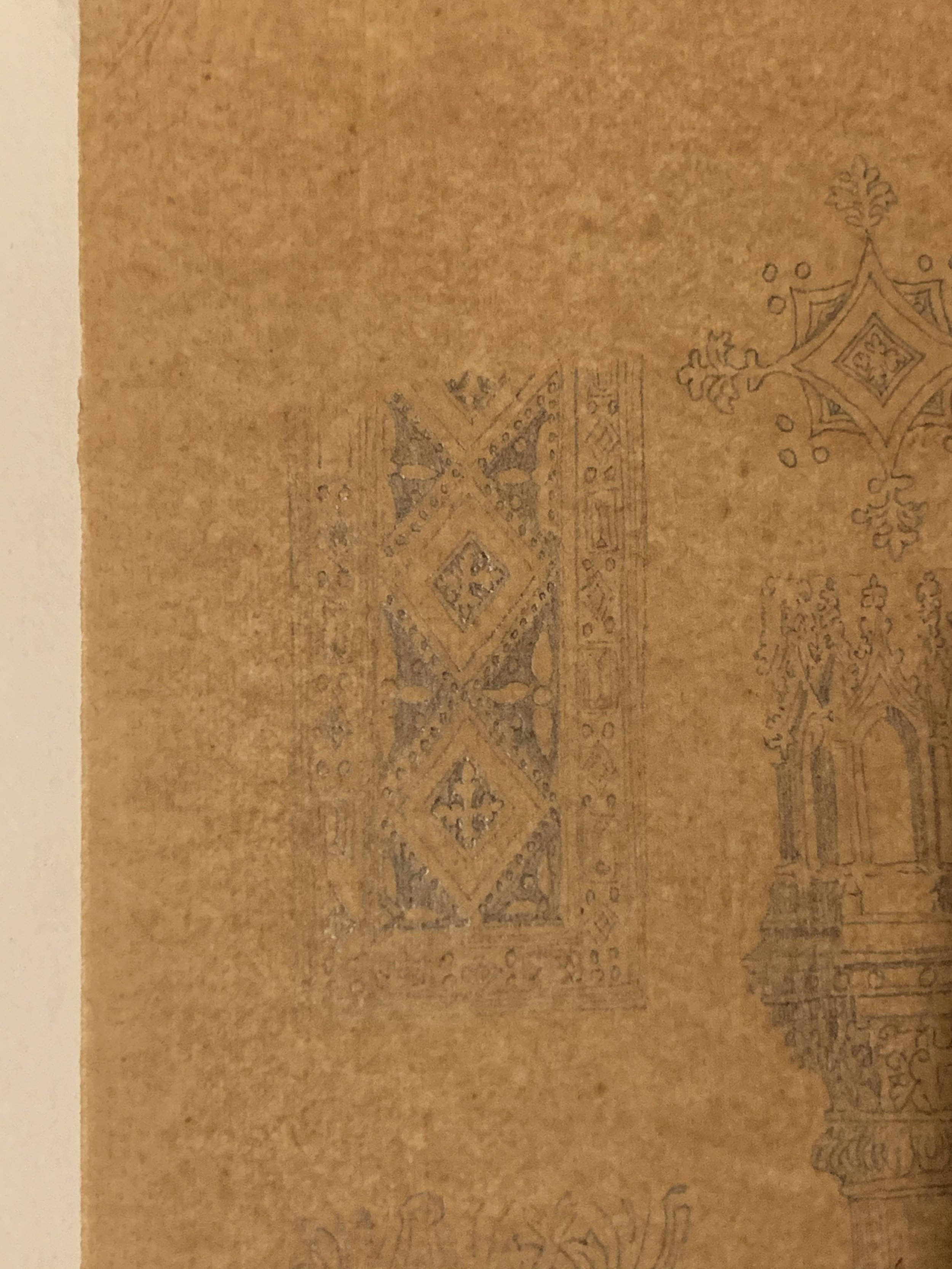

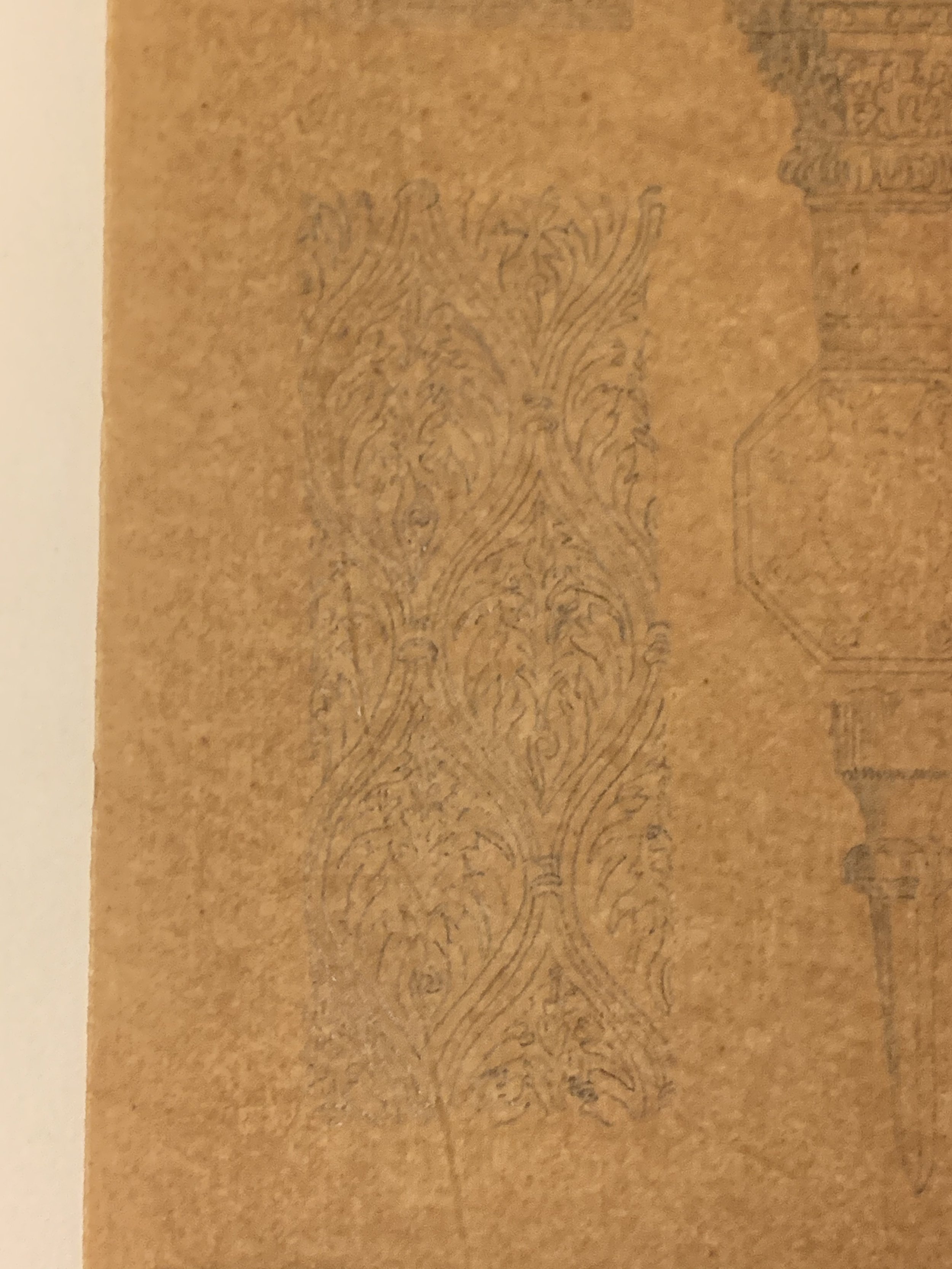

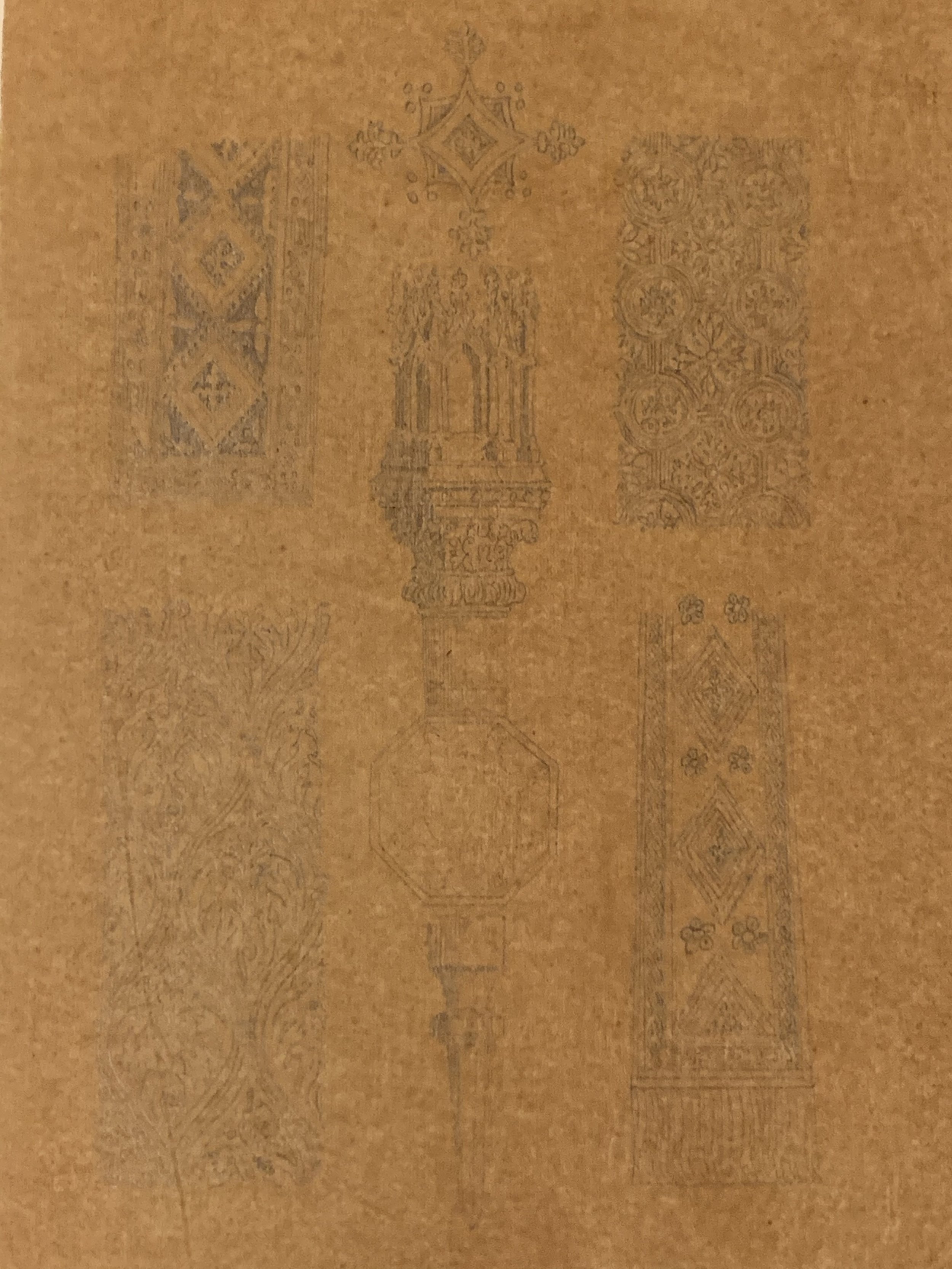

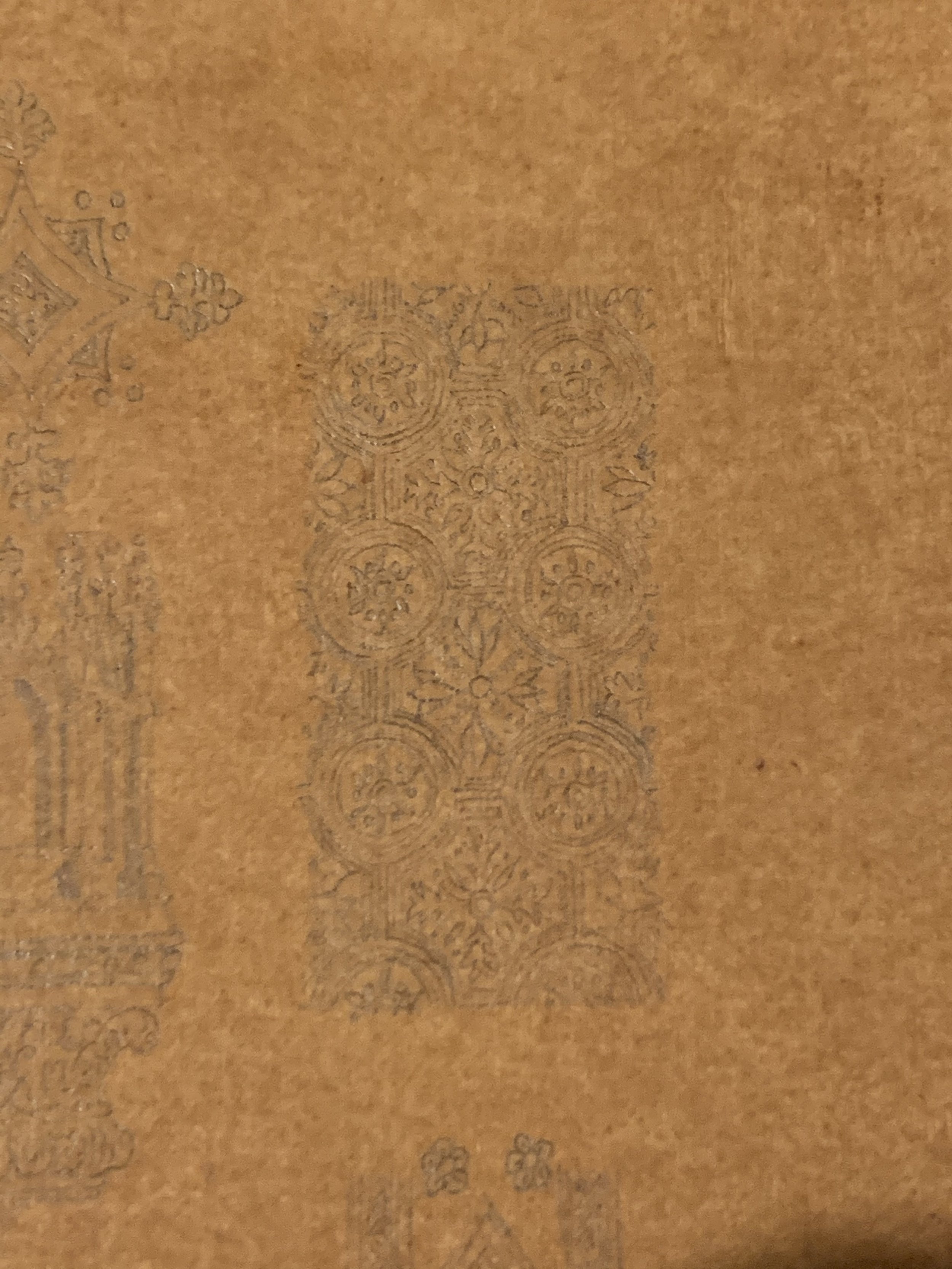

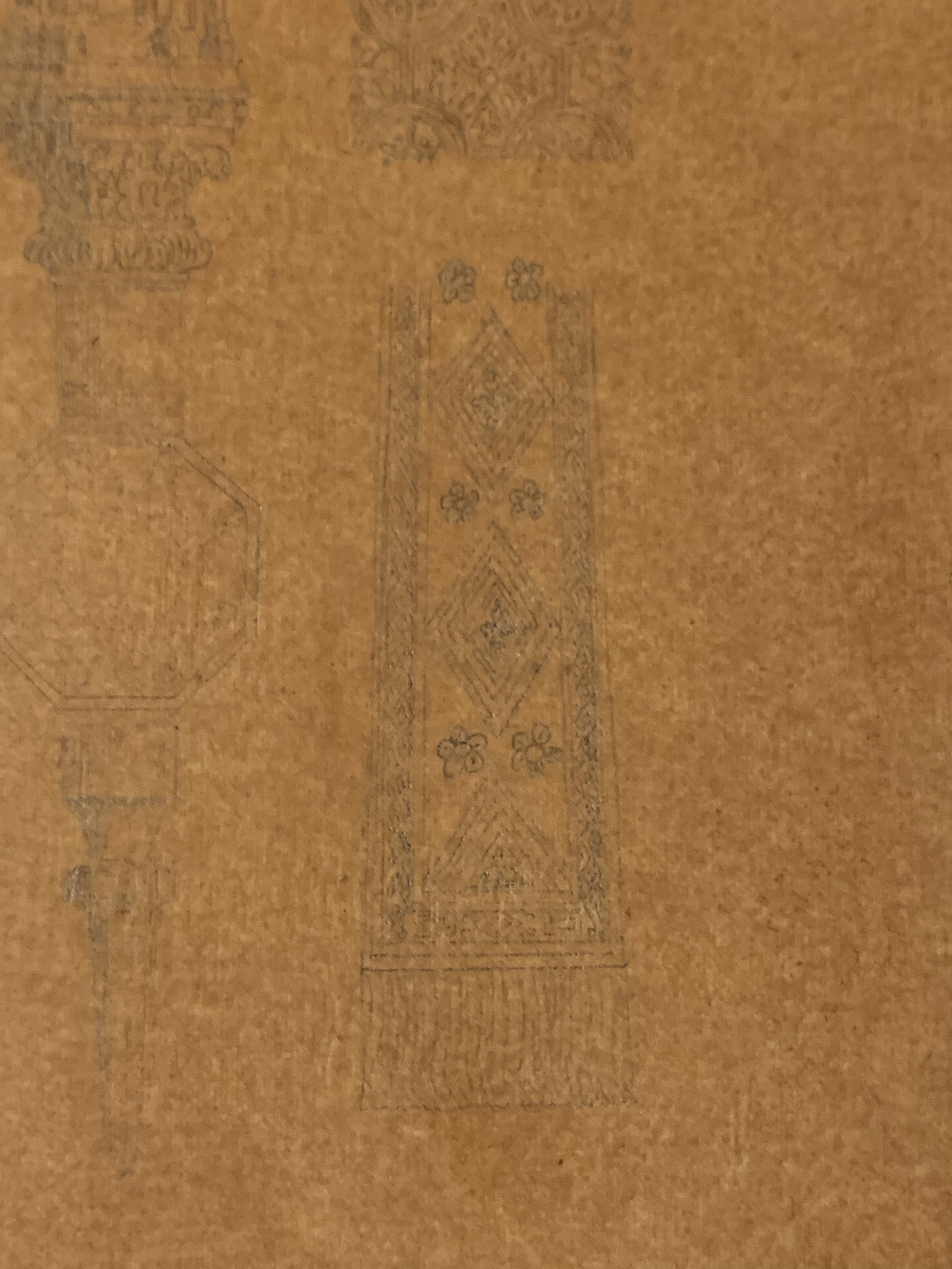

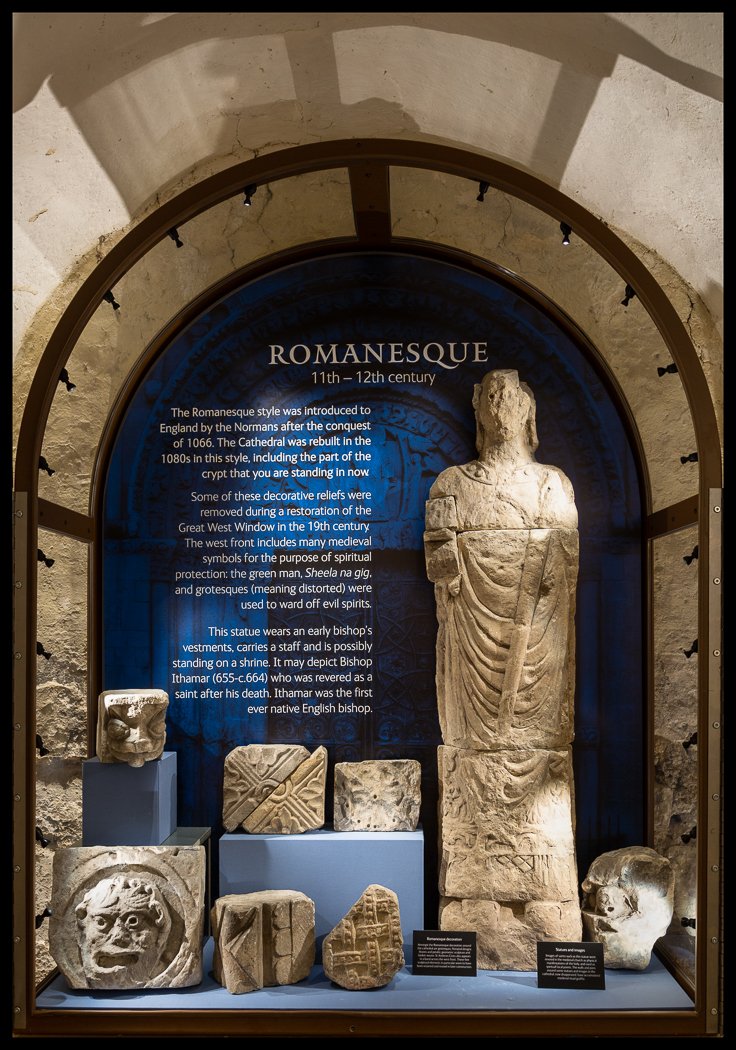

Many Romanesque sculptural decorations within the Lapidarium collection today were removed from the spandrels either side of the large perpendicular Great West Window during restoration work in 1825. These were themselves spolia reused around the time of the insertion of the window c.1490 and are presumed to have originated in the Caen stone refacing of the west façade c.1150, if not reused from the original c.1080. Cottingham’s sketches record the locations of the stones as they were removed, apparently with the intention they be replaced in the future, although no such campaign occurred.

There are notes that the collection of fragments taken from the west front was consulted during Pearson’s restoration campaign some 80 years later. Although their interpretation is at times ambiguous, several of the Romanesque fragments in the collection today can be traced back to Cottingham’s time through these sketches (for example, the grotesque face). Further stones are theorised to have resulted from this campaign, although their locations are only tentatively identifiable in Cottingham’s sketches (nos. 122, 129 and 130). The sketches also include stones and moulding forms no longer evident within the Lapidarium collection today.

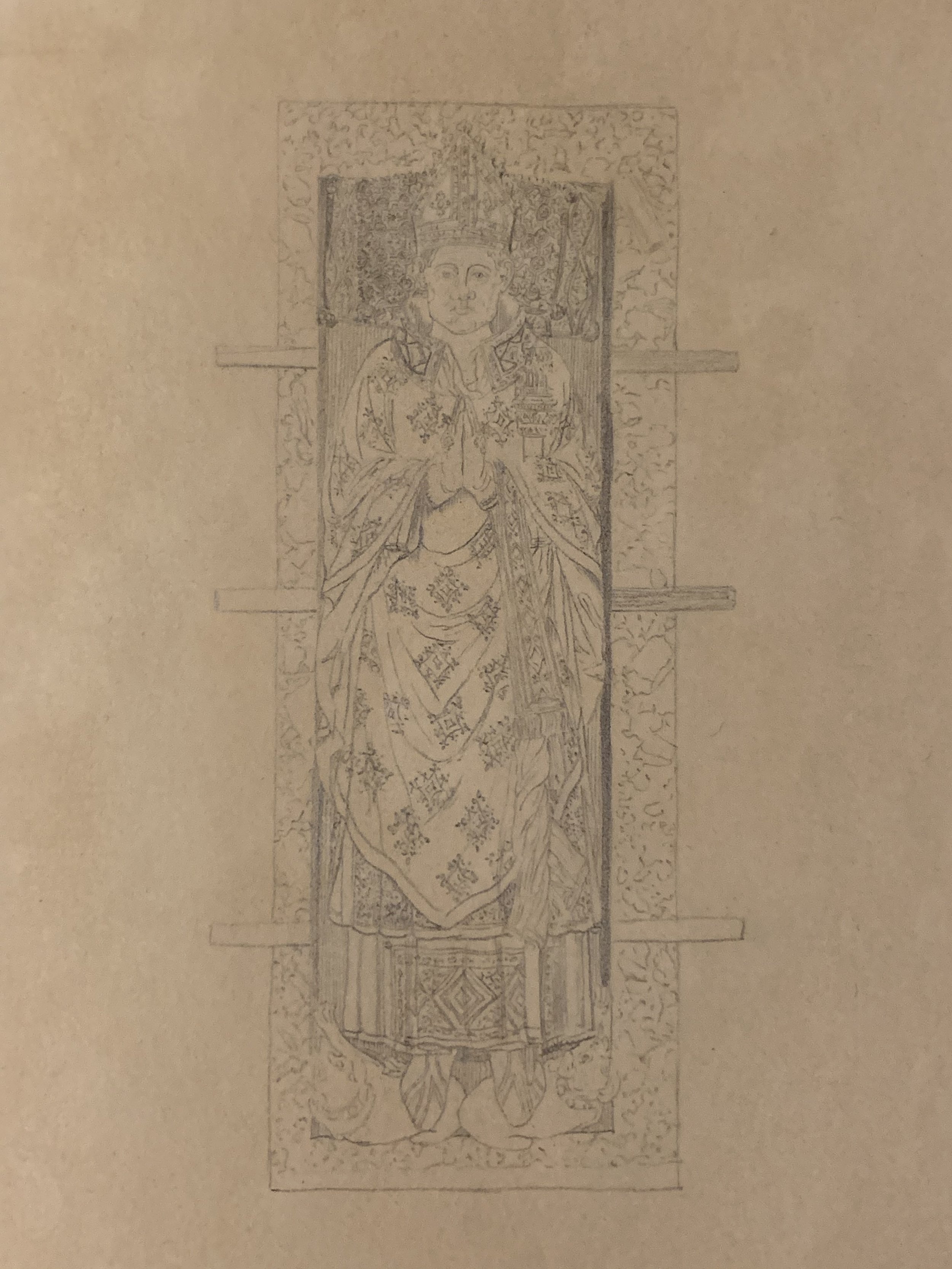

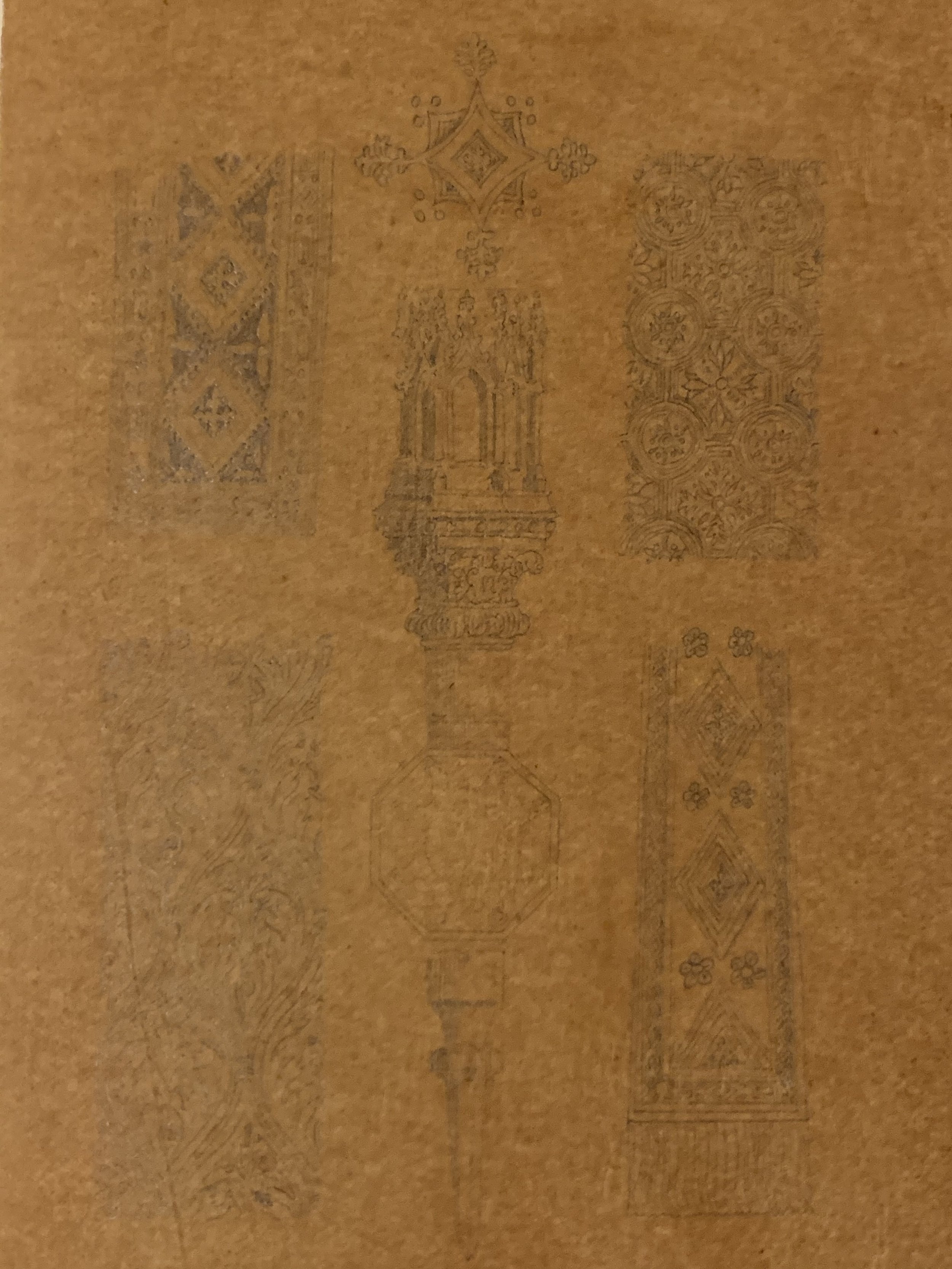

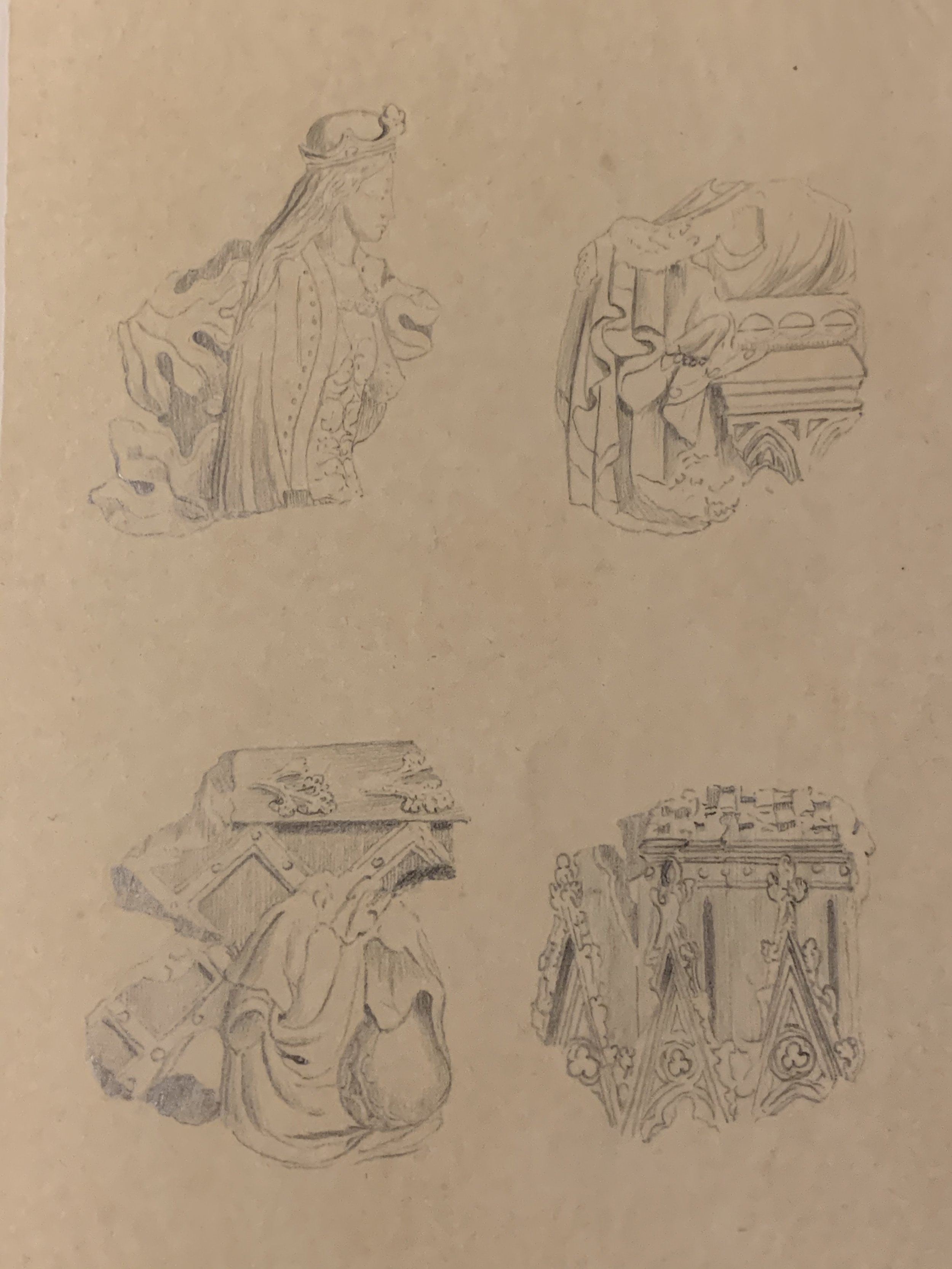

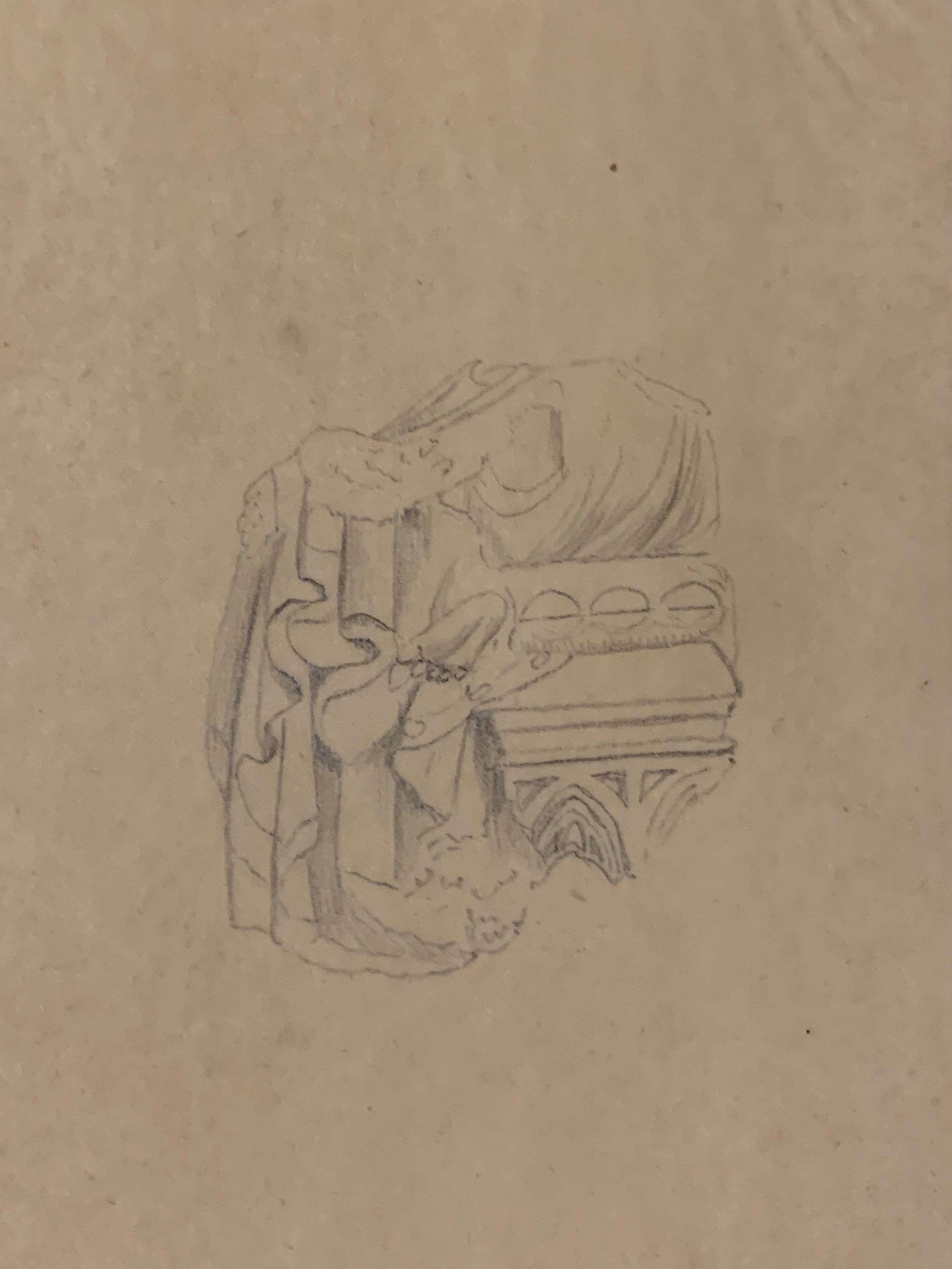

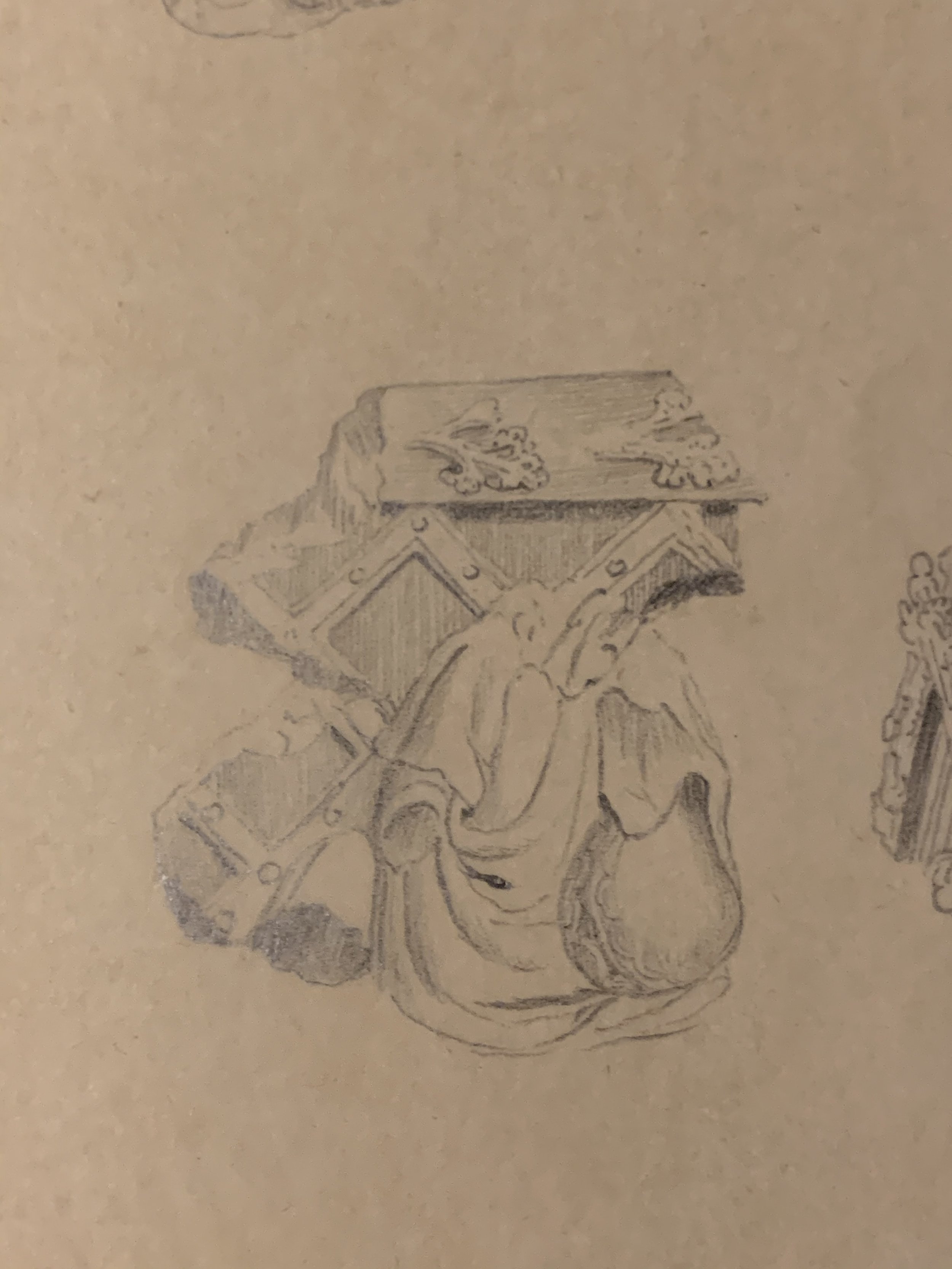

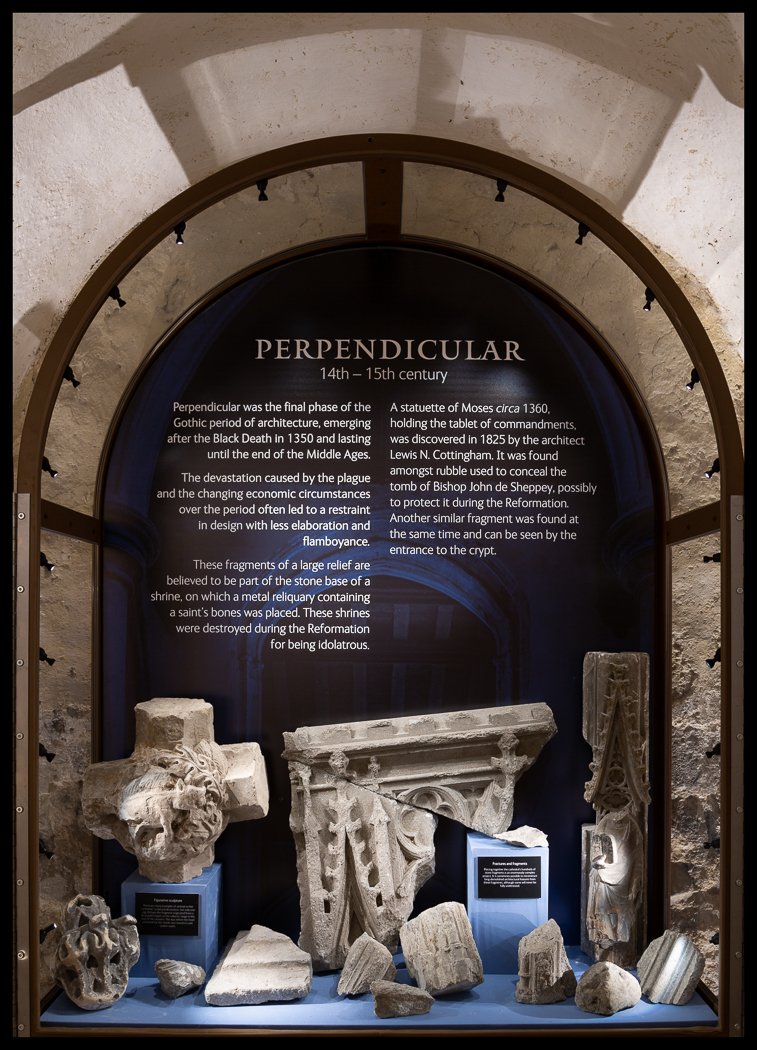

Also in 1825, ‘the brick wall that had (we know not when) been built up over the doorway, leading to St. William's Chapel, and that reached quite up to the roof, was taken down’ (Medway Archives DRc/Acz). A tomb of an unknown person was discovered with an exceptional painted effigy of Bishop John de Sheppey (d.1360), blocked up with rubble and a number of fine sculptural fragments.

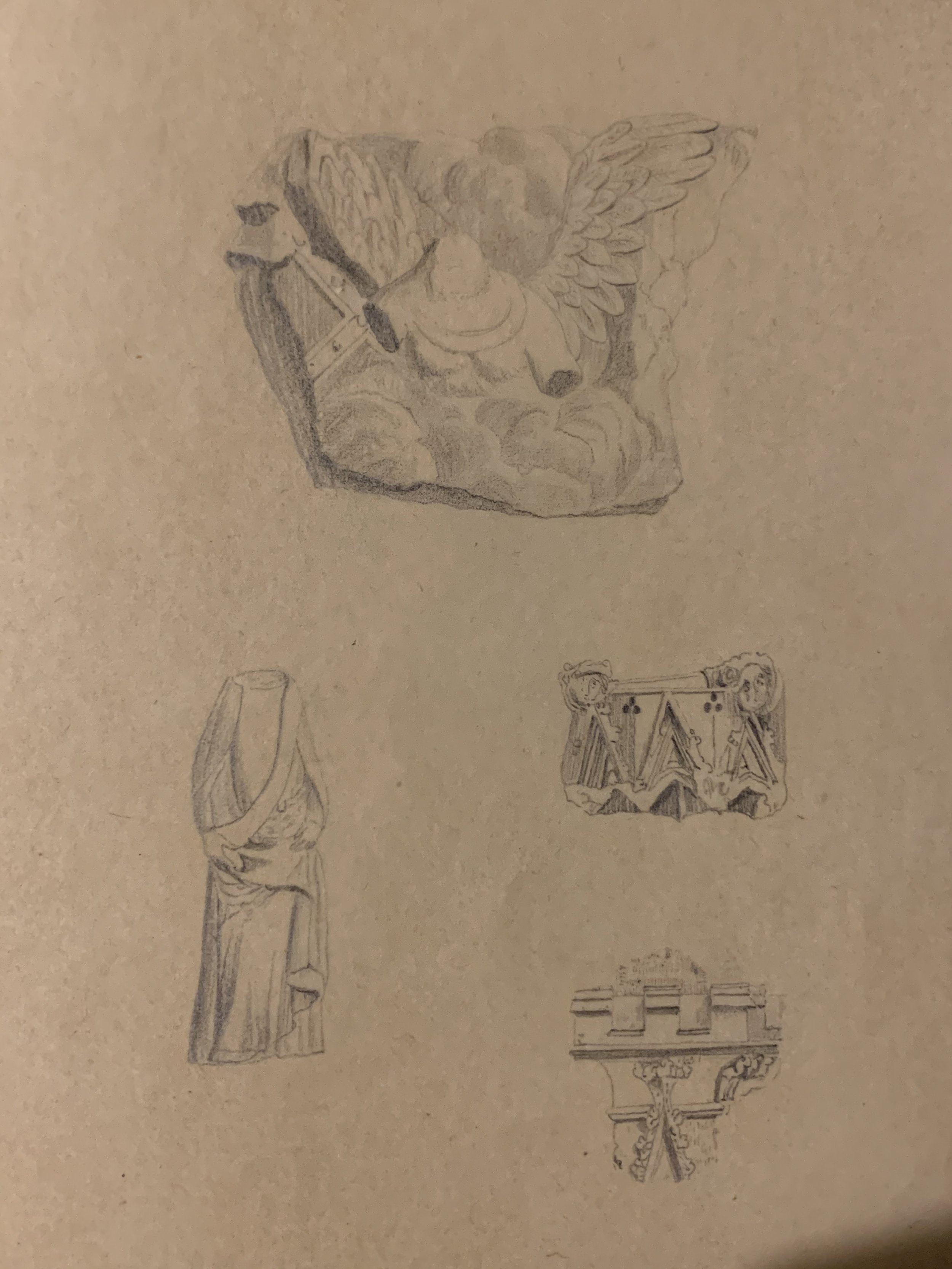

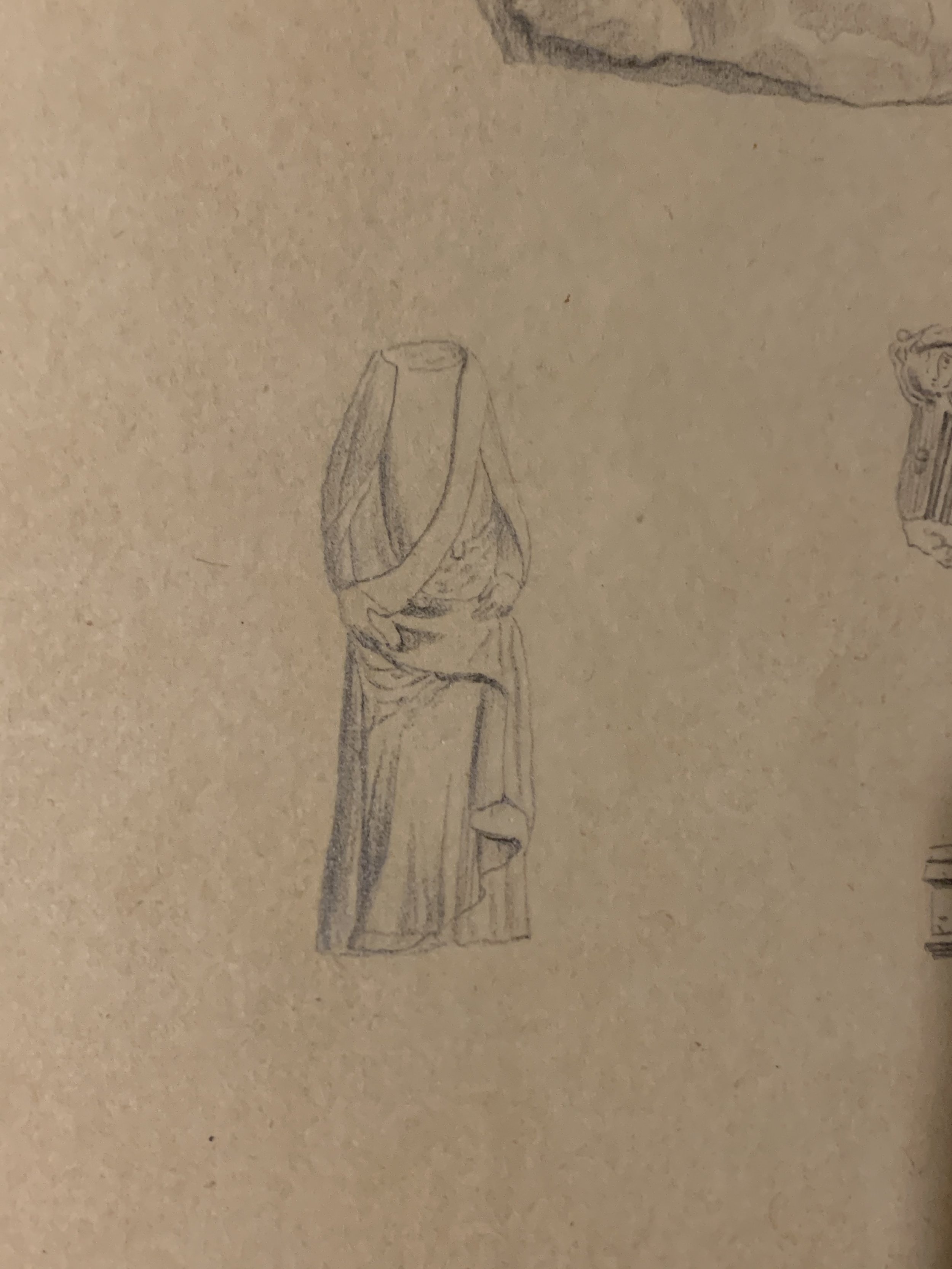

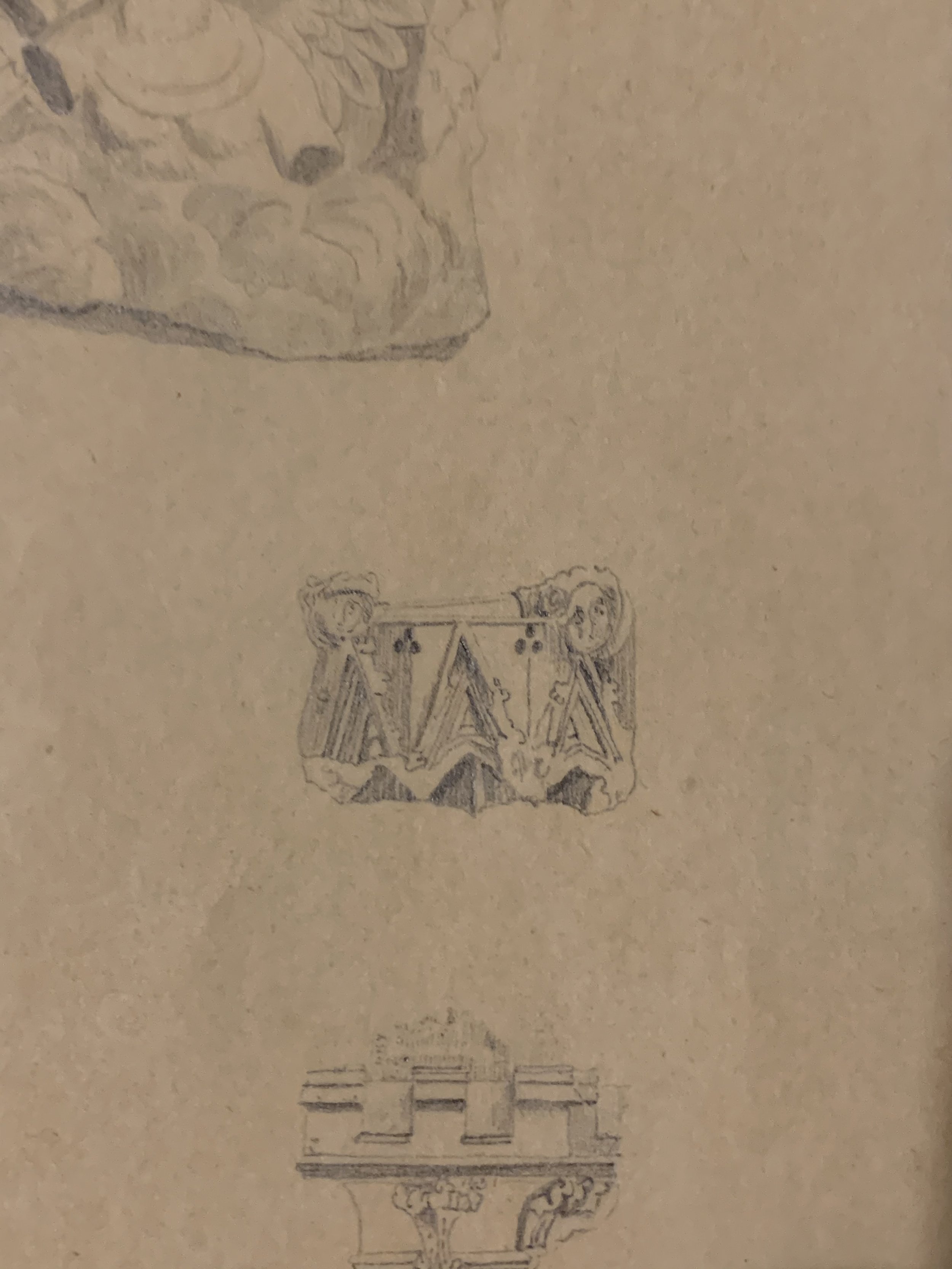

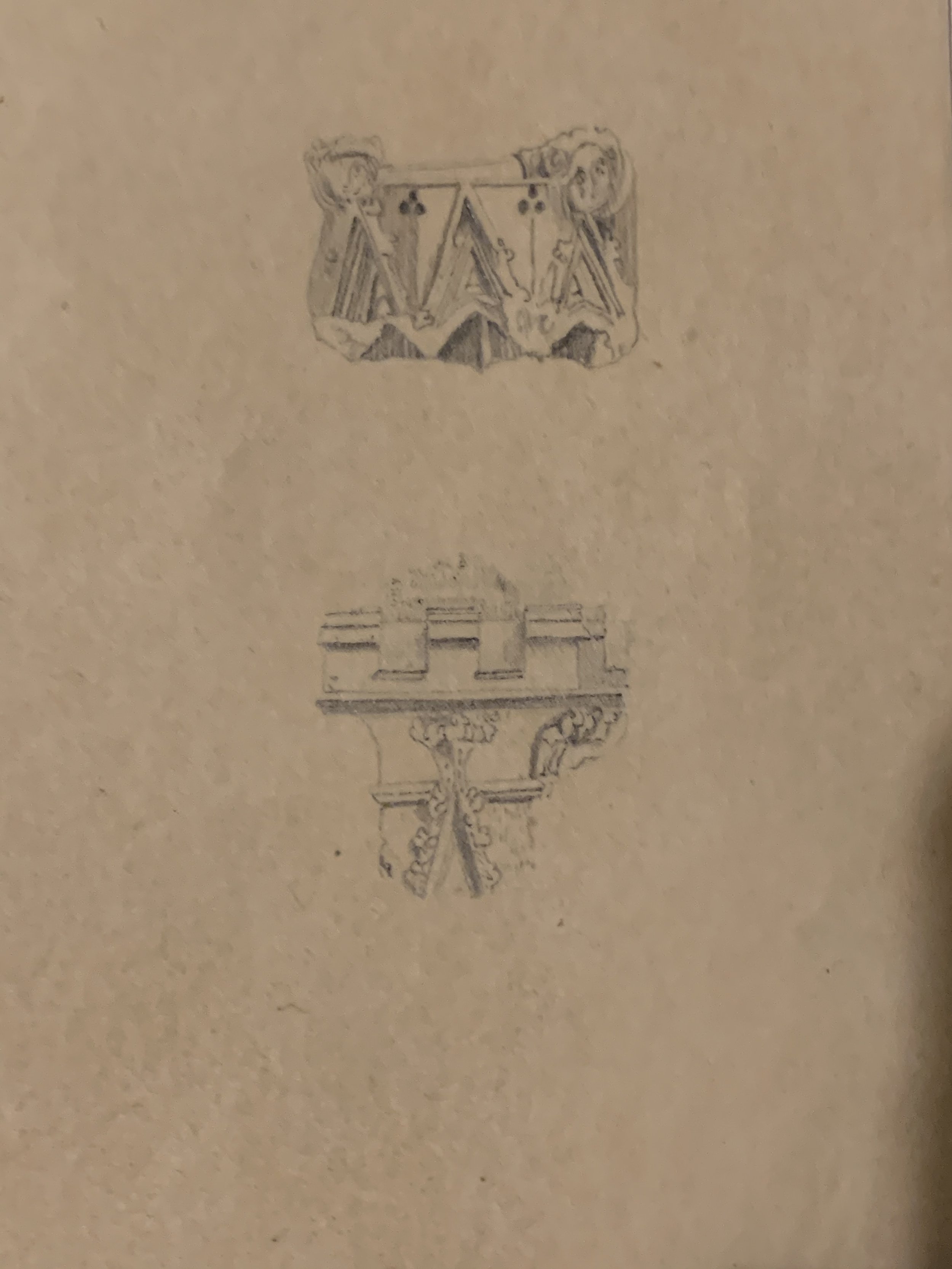

Cottingham had a remarkable series of sketches and lithograph copies produced of the tomb, effigy and fragments as discovered apparently intending to illustrate a report, although no resulting publication is known.

Identifiable within the series of sketches are 41, 42, 83, 105 and 108). This valuable record shows most items within the Lapidarium collection have suffered considerable damage and loss of material in the intervening two centuries. The heads of statue fragments 42 and 108 have been lost, and the uppermost portion of fragment 83. Not including broken pieces, eight fragments are no longer identifiable within the Lapidarium today. Stones within the collection evidently resulting from a similar context suggests the sketches may not have included all the items recovered during this discovery (for example, 29 and 86.

Further items were added to this assemblage. Fragment A2533 was recovered during underpinning of the west façade (Livett 1889), although three smaller fragments of another item of sculpture recovered during these excavations seem to have been lost (fig. 1.7). Several foliate voussoirs in the Lapidarium today seemingly resulted from Pearson’s restoration of the west façade, although the majority were heavily weathered elements in need of replacement. William St John Hope noted in 1898 ‘In the vault beneath the chapter-room are deposited a large number of carved and moulded architectural fragments, some of considerable beauty and interest, that have been found from time to time at successive “restorations”. Until quite lately these were scattered about the crypt, but have now been reduced to some kind of order by the care of Mr George Payne, F.S.A. They have yet to be sorted and labelled, before all record of them is forgotten’. No catalogue is known to survive from this time, although nineteenth-century photographs of the north end of the crypt room beneath the Chapter Room show the stones incidentally (fig. 1.8) with one close-up (fig. 1.9).

These photographs have been used to identify the date of accession to the Lapidarium collection and in particular discerning what stones result from Cottingham’s works on the west façade. An early twentieth-century photo from around the time of St John Hope’s remark presumably shows the order referred to.

A handful of the fragments in the Lapidarium collection can be identified from these photographs, although most remain obscured or indiscernible. A letter from Payne to the Chapter dated 9 October 1905 (DRc/Ac/21) records the ‘..abstraction by a stranger from Crypt of fragment of carving in stone representing head of our Lord’. Payne subsequently recommended the finest ‘relics’ be deposited at Rochester Museum, to which Chapter eventually relinquished. This seemingly comprised a collection of C17th militia uniforms and weapons, and possibly fragment no. A2533. The Rochester Museum and its successor the Rochester Guildhall Museum eventually became the repository of the three pre-Conquest sculptural fragment recovered from the Cathedral and Precinct (nos. A2531, A2532 and A2533, known by their Guildhall Museum accession number).

The area below the Chapter Room became a vestry before World War I and the crypt was used as an air raid shelter through both wars. A note by Letharby dated 8 th March 1921 (DRc/Emf/135) suggests to ‘bring a few choice fragments from the store and attach to the walls [of the South Quire Aisle’. No stones are recorded as ever being exhibited in the South Quire Aisle, so this effort may have resulted in the heralds of the Cayley and Somer tombs hung in the crypt vestry/slype area until the 2015 renovations to this area.

Further additions to the collection are evidenced and occasionally recorded, such as fragments from a fine late medieval tomb or shrine (nos. 31, 32 and 33) recovered from excavations in 1924 within the C13th tower to the north of the cathedral known colloquially as ‘Gundulf Tower’.

Anneliese Arnold, wife of Dean John Arnold (1978-1989), noted that despite Payne's efforts the majority of fragments had since been scattered again, a few preserved elsewhere in the cathedral, but many ‘simply piled up on a ledge inside the ruined Chapter House, exposed to the weather. Some of the best have disappeared, doubtless taken as souvenirs or ornaments.’ Following discussions with Cathedral Architect Emil Godfrey in 1981 Arnold established the Lapidarium in a chamber over the east of the North Quire Transept.

A portfolio in the Chapter Library records the logistics and concerns at the time (Arnold 1994). The Cathedral Campers repaired and redecorated the space in 1986 and repaired the walls and floor. Cathedral Surveyor Martin Caroe designed the shelving erected by the Royal School of Military Engineering and Claire Walker and Leslie Hudson are credited with collecting 245 stones and moving them up to the space via a spiral staircase in the North Quire Transept (Arnold 1994). Arnold’s numerical catalogue of the stones begun in 1992 records 252 stones including a nine very large stones remaining around the Cathedral floor at that time, as well as smaller collections of tile, wood and assorted finds. This 1992 catalogue corresponds to tip-ex markings on the stones and it is this numbering system that has been extended by this survey. Additional fragments, excavation finds and historic bric-a-brac accumulated in the Treasury Lapidarium over the next 25 years to the point that navigability of the space was restricted.

The Lapidarium established in 1992 by Anneliese Arnold, photographed in 2015.

Arnold’s Lapidarium catalogue has been supplemented with many fragments recovered from various excavations, particularly those within the cloisters and crypt in 2014 (Keevill and Ward forthcoming). Stones are regularly unearthed by the gardeners, or else identified reused as garden features. Today, the collection comprises over 500 stones ranging in date from the eighth to the nineteenth centuries. The contents of the Lapidarium were moved to a space opposite over the South Quire Transept (figs. 1.12 and 1.13) after the refurbishment of this space in 2018, a process concluding at the time of this survey. The appropriate housing of the Lapidarium collection represents an enormous logistical achievement over many years. However, what has been gained in shelf space has been lost in accessibility. The new Lapidarium is accessed via an adventurous route up and across the roof spaces and down through two spiral staircases and a landing installed in 2018. Nevertheless, the new Lapidarium presents a permanent home for this significant collection and should prevent further disintegration or losses from the assemblage in future.

In 2010 a lending program to London City & Guilds stone conservation students was initiated with stones transferred to be worked on over the course of an academic year. This has led to the cleaning, consolidation and classification of a significant portion of the stones catalogued in 1992.

Recent recording has included aerial photography for the production of models of the cathedral’s numerous pinnacles. Some 200 stones on the site have resulted from replacing these pinnacles in several campaigns. George Gilbert Scott replaced most if not all of the presumably original pinnacles during a project to lower the cathedral roofs and restore the clerestory level in the 1870s. By the end of the twentieth century, most were in need of significant conservation. The two pinnacles over the South Nave Transept feature patchwork repairs from 2008 (Worssam 2008), not visible from ground level.

The north-west pinnacle of the north nave transept tower and the south-side presbytery buttress pinnacle were replaced in 2018. This SfM and photographic record has afforded the means to discern the nineteenth-century stonework around the Cathedral Precinct and keep this distinct from original medieval designs which are now added to the Lapidarium collection. Close-up photography and the development of the SfM record of in situ architectural features has been essential to stylistic comparison and Rochester Cathedral Lapidarium and spolia 29 Jacob H. Scott 2021 typological classification in identifying the provenance of items in the Lapidarium collection and in placing them into context for public interpretation.

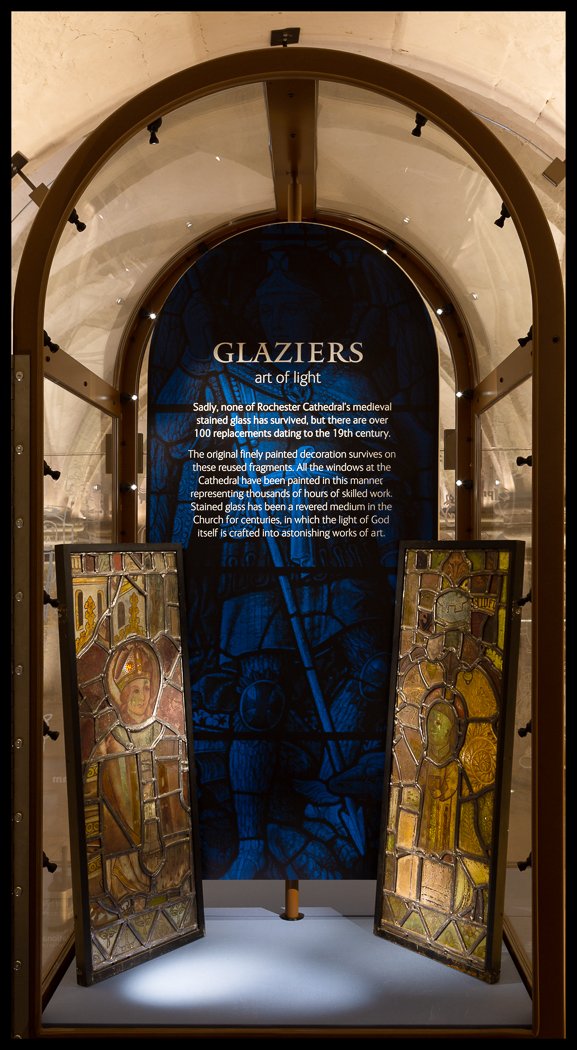

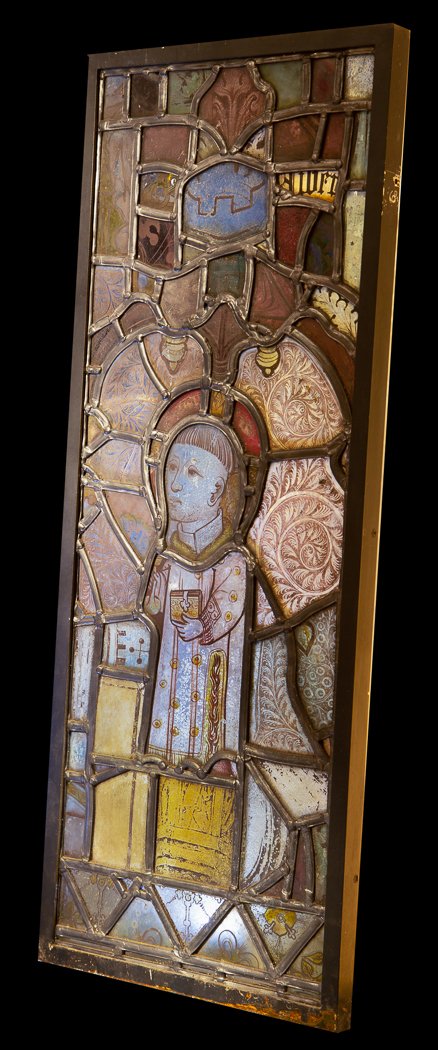

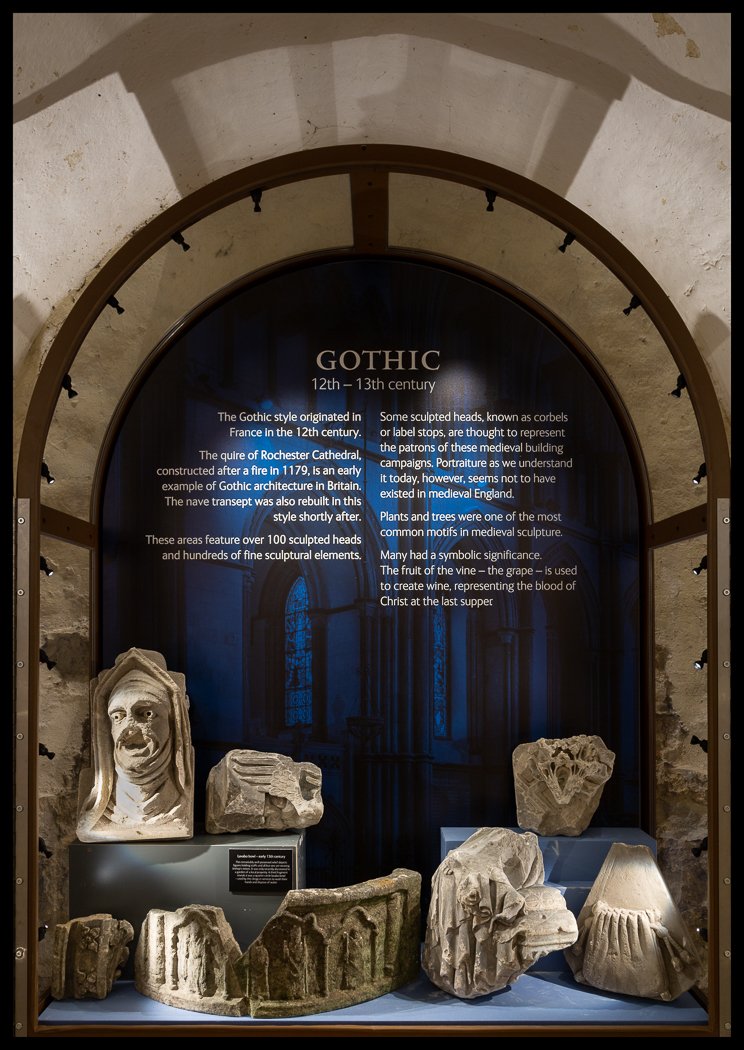

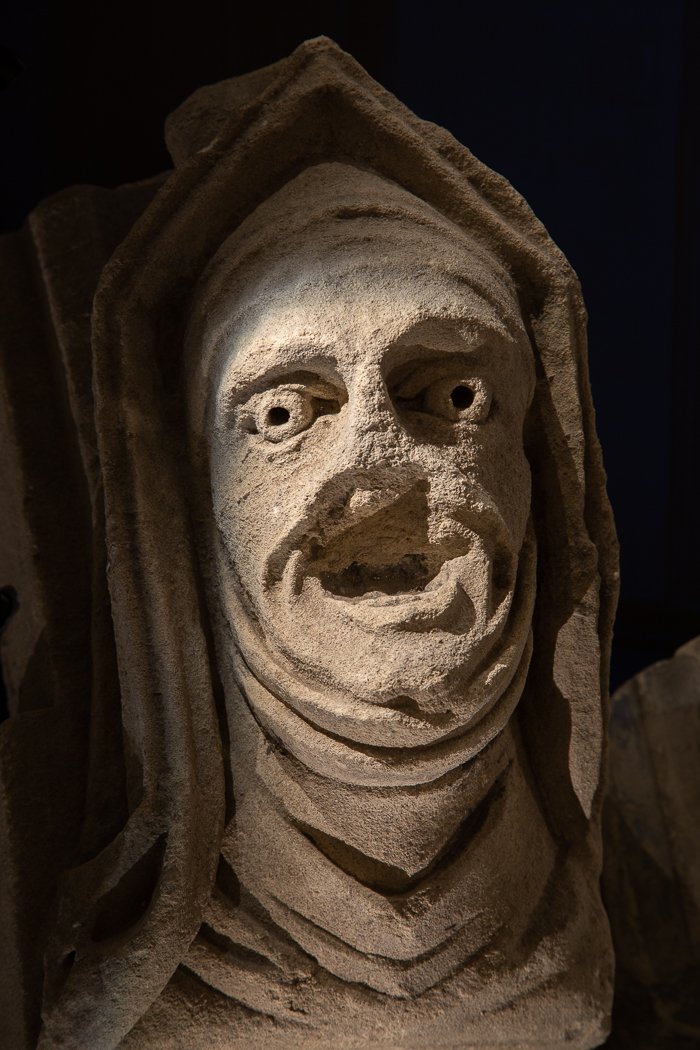

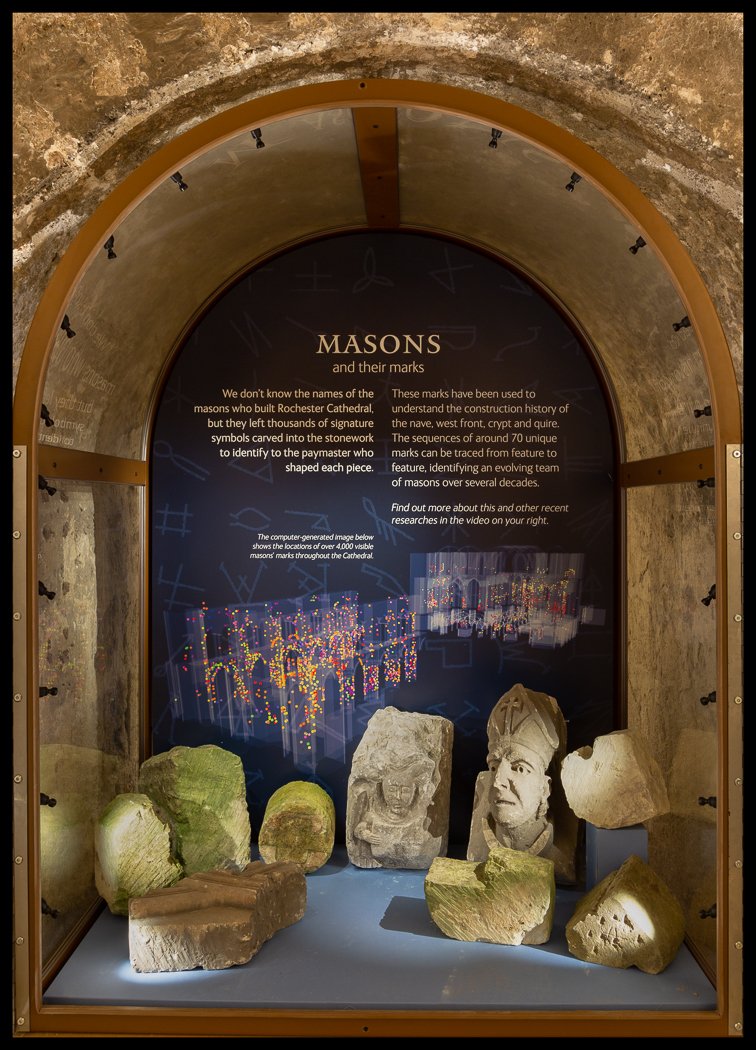

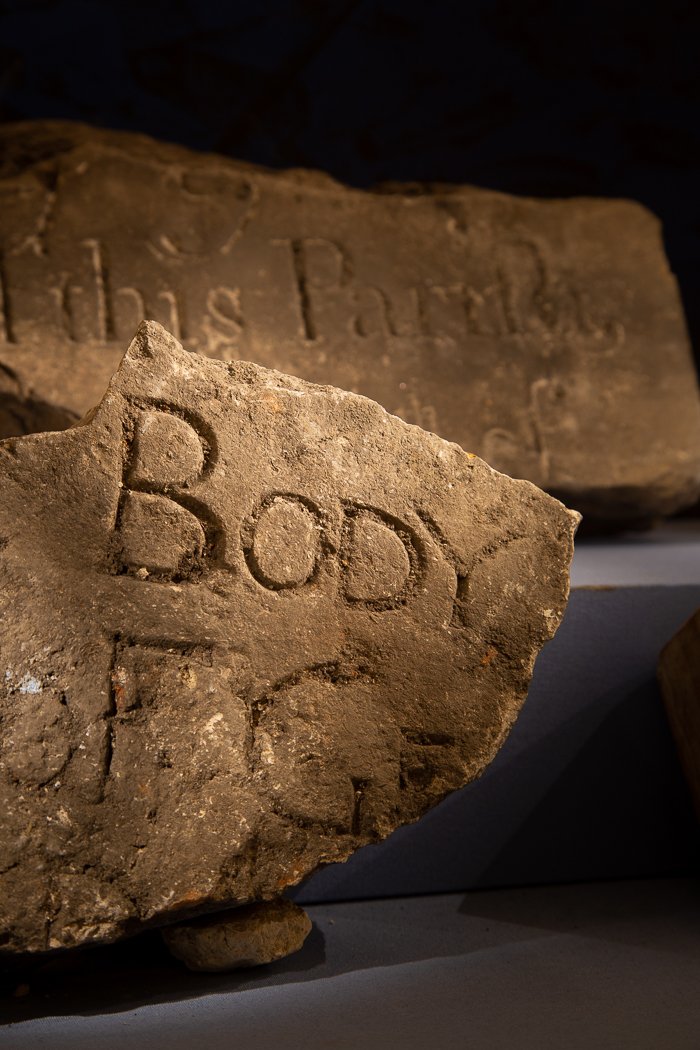

Photographs by Clive Tanner of the Fragments of History exhibition 2018-2019 in the Cathedral Crypt.