Graffiti in restricted spaces

/

Graffiti in restricted spaces

September 22, 2021

Several of the largest graffiti clusters occur within the non-public, seldom-used or inaccessible areas of the cathedral, entered by only a few hundred people over the last 500 years.

A cluster of 28 pencil graffiti behind a Purbeck shaft at the east end of the south quire aisle records the names of choristers from the late nineteenth century, many identifiable in the choir registers. Often a date ‘entered’ and ‘left’ are included within graffiti. The south quire aisle is used today by the choir as they wait to process into services. Identification is significantly aided in the investigation of alphanumeric graffiti clusters in non-public areas.

Garth House

Formerly a choir school, theological college and now the cathedral’s administrative offices, Garth House was constructed in the 1870s from red brick with sandstone dressings.

Garth House, forming the southern boundary of the cloisters. A former choir school before its conversion into administrative office, its exterior features over 300 inscriptions.

Garth House overbuilds and backs on to parts of the south range of the cloister of the cathedral, formerly the refectory. Around 300 graffiti inscriptions occur on the exterior of the west and south walls, and the wall enclosing the yard on the west of the building. Those that are dated range from the 1880s to the 1960s, from the time that the building served as a choir school. Several inscriptions feature a ‘date entered’ and ‘date left’, often being resident for three years. These inscriptions are cross-referenceable with registers over the period.

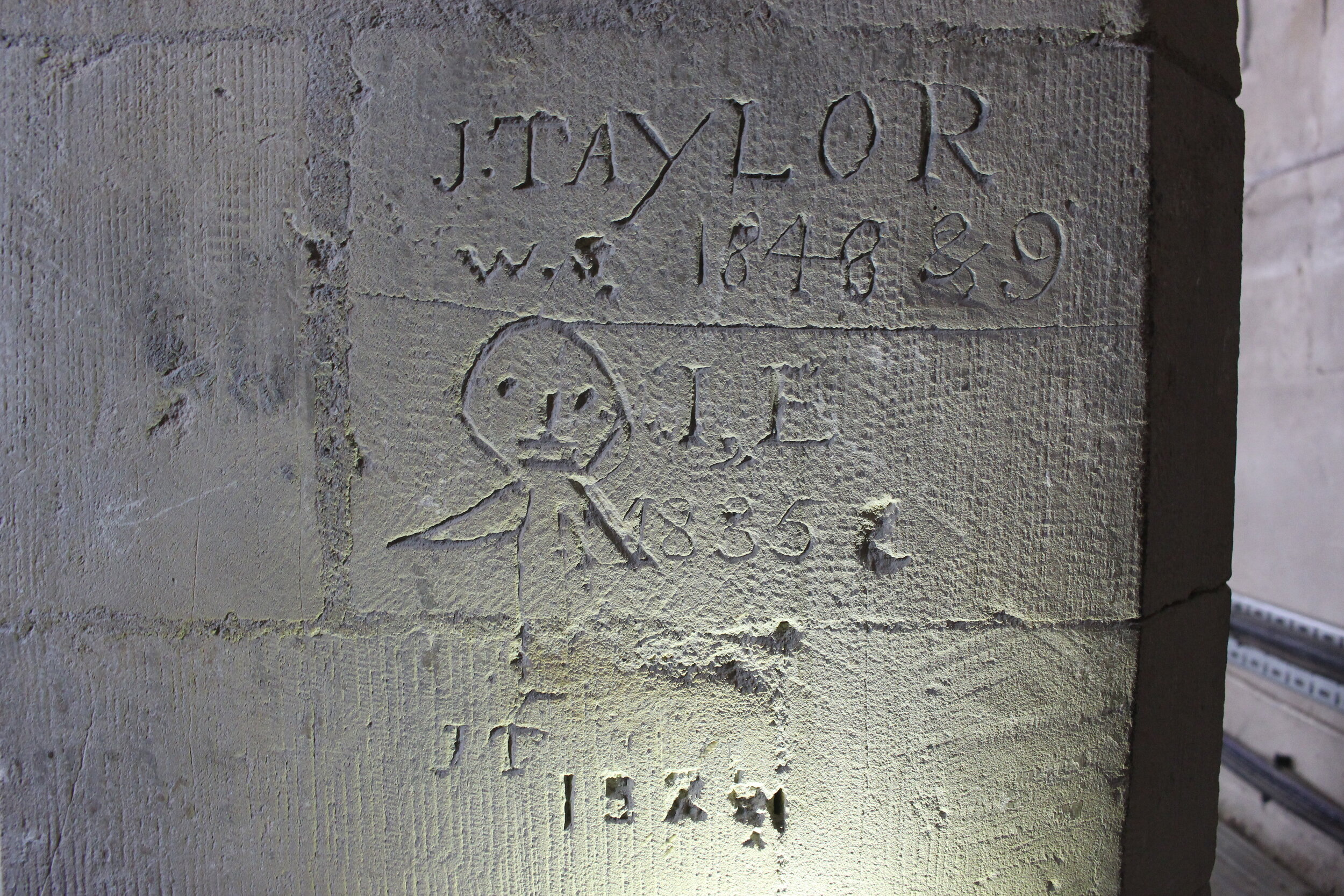

This cluster of inscriptions includes several World War-era graffiti, including the far from convincing ‘ADOLF WAS HERE / 1940’. A semi-spherical indentation within the porch of the building will be familiar to any visitors to twentieth-century red-brick cinemas. The diameter of the graffito is 31mm, the diameter of the old British Penny circulated from 1860 to 1971. Intriguingly, an inverted VV mark has been used within one inscription of the west wall, although the density of inscriptions makes it difficult to identify which initials it might accompany. Only a handful of crude figurative designs can be identified, of stick men or what appears to be a beetle (see ).

The inscriptions are almost entirely on the west wall and the south wall west of the main entrance. It seems likely that this denotes the direction of queueing to get into the building. Several red-brick walls in the basement also feature alphanumeric inscriptions just visible beneath a thick layer of whitewash. Unfortunately, none are dated. This whitewash covers almost all walls of the basement. Office furnishings or dividing walls obscure any further surviving inscriptions within the building.

As Garth House was used as a choir school for a limited time, and seemingly has seen little or no other inscriptions after this time, even undated inscriptions are identifiable with reasonable confidence, in contrast to the vast majority of undated initials found within the Cathedral.

Triforium and roofs

The obvious lack of redecoration, weathering or erosion of many thousands of hands such as which afflicts the lower areas of the building results in crisp inscriptions that often seem at odds with included dates. This perceived permanence acts as a catalyst for the growth of these clusters, including hundreds of names of glaziers, plasterers, bricklayers, bell ringers and clergy. Many of these can be matched with those named in documented building campaigns over the last two hundred years. The archives of the Dean and Chapter of Rochester Cathedral are kept by the Medway Archive Office. Holbrook (1994) indexed the invoices, receipts, surveys and correspondence within these records for the years 1540 to 1983. When referencing an indexed document, the Medway Archives reference number is provided. Holbrook’s index has also been made available on the Research Guild website.

Eight spiral staircases grant access to the triforium and the roofs, four within the west façade, two at the north of the north quire transept and two at the east end of the presbytery. Cottingham blocked another staircase to the Indulgence Chamber at the same time as another set of steps from the south quire transept to the crypt. Some of these access towers contain graffiti clusters. A dispersed cluster occurs within the access tower at the north-east corner of the north quire transept, with 16 dates from 1856 to 1915. A door halfway up this tower leads onto the triforium, with the doorway including two partially legible seventeenth-century dates. The wear of the stone steps in this tower suggests this was the main access route to the Treasury, roofs and Bell Ringer’s Chamber for many years.

The triforium (a gallery below the level of the windows) runs through the nave arcades and below the west window, around the nave and quire transept, either side of the centre quire and around the presbytery. Two hundred eighty-eight names and initials adorn the reverse of shafts and piers, invisible from ground level. They most often occur in small groups of just a few graffiti.

Graffiti behind a pier on the triforium of the north nave transept.

Dated inscriptions occur every decade from the 1790s, with two legible inscriptions of 1703 and 1704 and possibly earlier partially obscured by thick whitewash. A Thomas Collier left three inscriptions on the quire triforium on the same pier, in 1798 and 1799 with a third date illegible. A. Edney inscribed their name in the Indulgence Chamber four times, in 1880, 1881, 1887 and at another indiscernible time in the 1880s. Other inscriptions by an A. Edney occur on the nave triforium and a wooden handrail in the south quire transept attic. An artful but undated ‘James Oram’ is inscribed on the obscured face of a shaft at triforium-level in the southern arcade of the nave. A James Oram was a plasterer employed from 1843 to 1848 (DRc/FTb/174, DRc/FTv/199, DRc/FTb/175, DRc/FTv/203). An S. Oram features in receipts for decoration and plastering from 1847 (DRc/FTv/202). Perhaps it was a relation of either of these that neatly inscribed ‘Wm Oram’ in the north nave transept triforium. H. Cronk, presumably a relation of the creator of the nave triforium cow, created six inscriptions in 1888, 1889, 1890, 1891, 1892 and 1898. Several other doodles are present amongst the triforium inscriptions, some crude and some skilfully crafted, including a bird, a stick figure, and several sexfoil.

These are the most likely inscriptions within the building to include an occupation, significantly aiding their identification within the maintenance records. W. Carter lists their occupation as a painter in 1815 in an inscription on the quire triforium. E. Holding and H. J. Parfit list their occupations as glaziers in an 1872 pencil graffito in the Indulgence Chamber. ‘WNF’ is recorded as a painter in an 1888 inscription on the quire triforium. Another painter - G Lane - lists their occupation twice, once in paint on the quire triforium in 1910, and again in an inscription in the Indulgence Chamber in 1916.

The largest graffiti cluster on the triforium is that on either side of the Great West Window where the wider passageway and enclosing walls provide a more secure walkway for the light-hearted. Here 42 dated inscriptions occur almost every decade between the years 1731 to 1997.

A chamber above the small aisle to the east of the south quire transept is colloquially known as the Indulgence Chamber (a modern name). An inscription on Caen stone at the south-west corner of the room is dated 1623, although there are no other Early Modern inscriptions here. The stairways leading up to this chamber from the transept and crypt below were filled with red brick by L. N. Cottingham during strengthening works in the 1820s (DRc/Emf/135). Access to this room has since been limited to a route via the triforium, making this one of the most difficult areas in the building to access. Cottingham also had installed several iron braces and a red brick wall which now divides the chamber in two for structural purposes. It is this wall which has accumulated the largest modern graffiti cluster in the building. Two hundred twenty-four inscriptions, many one-per-brick, include 80 dates every few years from the mid-nineteenth century. G. Hilburn may have started this tradition with an inscription dated January 5th, 1848. Sometimes the same name occurs every year or two for a decade or more. The cluster contains the most full-name inscriptions and occupations of any in the building and includes several members of the clergy leading up to the last 30 years.

An intriguing identification has been achieved with an inscription on a beam from a previous incarnation of the bell frame (6.14), preserved during its rebuilding in 1959 (Holbrooke 1984, DRc/DE/209).

The only complete name reads ‘THOMAS KERISOM:1636’. A Thomas Kerison was a witness to the will of William Cripps, Alderman of the City of Rochester, dated 2nd Dec 1633. During a survey of the bells in 1904, an inscription revealed that the 3rd 11cwt bell (around 560kg) was cast in 1635 by the founder J. Milman. It seems plausible that Thomas Kerisom/n, apparently a man of some standing in Rochester society at that time, was invited to view the newly installed bell, perhaps as part of an inauguration ceremony or blessing. That such an inscription was deemed appropriate from during this event provides rare informed ethnographic evidence of social acceptance of graffiti at Rochester Cathedral during the Early Modern period. No other record of this event has yet come to light.

The photographic graffiti survey at Rochester Cathedral begun in 2016 has recorded over 7,000 inscriptions from the 12th to the 21st century.