Somer tomb heralds, 15th century

/Somer tomb heralds

15th century

Ieva Stradina’s in-depth study of one of five Somer family heralds reveals the story behind a tomb destroyed around the time of the English Civil War.

The object is one of five coats of arms to come from a Somer family tomb that was located in the Cathedral nave until the seventeenth century. The tomb was seemingly broken up before the English Civil War and for a while the coats of arms were hung in the nave - these shields ended up in the crypt at the beginning of the 20th century and remained there until c.2015 when the crypt was redeveloped and they were moved to the new Lapidarium.

Five coats of arms from Somers family tomb.

This is a summary of the condition and treatment report on the cleaning, conservation, and investigation of one of the heralds over the 2021-2022 academic year by City & Guilds London Art School student Ieva Stradina, submitted for BA (Hons) Conservation of Stone, Wood and Decorative Surfaces. The full report is available here

Heraldry

A coat of arms is a hereditary device, borne upon a shield, and devised according to a recognised system. This system was developed in northern Europe in the mid-12th century for the purpose of identification and was very widely adopted by kings, princes, knights and other major power holders throughout western Europe. The shield is the heart of the system. (Friar and Ferguson, 1993)

Distinct from Heraldry, a Coat of Arms is the broader design around the shield. Coats of arms were adopted for the practical purpose of identification by those who participated in warfare at a high level, becoming a necessary part of tournaments, held between European nobles, as it enabled participants and spectators to identify those who performed well. Coats of arms were inheritable, giving them an additional significance. They passed from father to son, as did lands and titles, and thus could serve as identifiers of specific lineages as well as of individuals. Different members of the same family could be distinguished by the addition of small devices or charges to the shield. (Gwynn-Jones, 1998)

Partitioned in half vertically (per pale), the coat of arms bears representation of a married couple - both husband and wife having acquired their shields on inheritance part, represented by further quartering of each section horizontally. The Fess or Heart point of the shield is raised creating a curve, this is perhaps to represent the convex shape of the shield worn at war or tournaments. (Plate 5) (Kelley, 2003)

The object can be dated by the carved ornaments, the shape of the shield as well as the symbols depicted and the way they have been grouped. The shape of the shield with a pointy base and flared chief parts is characteristic to c1600. The dexter side of the shield is partitioned in 9 segments; this did not come into fashion until the Tudor times. (Gwynn-Jones, 1998) A fess dancetty is displayed on the sinister side, it is a symbol that belongs to Baron Somers’ (1651 -1716) family and indicates a slightly later period of mid 17th Century. (Lawson, 1858)

The front elevation of the shield in raking light showing partitions.

The colour and surface texture used in heraldry is just as important as the symbols, and can be used to differentiate between families or individuals. The detailed carving of the shield has deteriorated to a point where it is hard to read the ornament, equally the paint scheme is also hard to identify without further analysis. The ancestry, as shown in the plate 6, has been derived through literature research and is based mainly on the Archaeologia Cantiana (1858). See Appendix 1 for more information on ancestors and symbolic meaning of the elements.

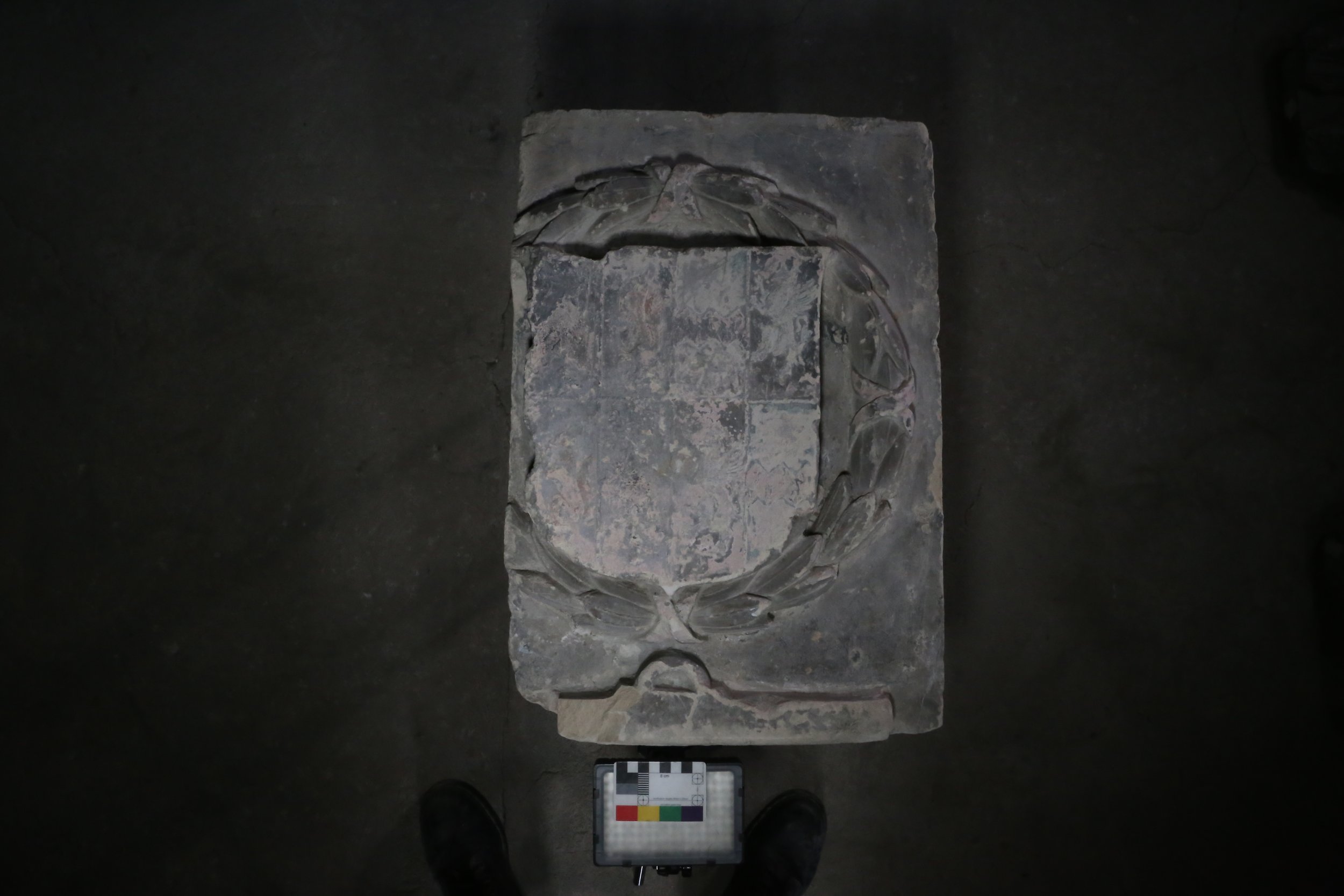

A carved, polychromed stone Coat of Arms. Made of oolitic limestone. (See Chapter 6 for material identification) The carved ornament has a rectangular base, a laurel leaf wreath surrounds the shield. The top edges of the shield are slightly curved outwards and the central part is convex.

The laurel wreath ornament does not have a complete, round shape - the proper left side of the carving ends with a straight edge as if cut through the centre of it. And so the whole ornament is positioned slightly towards the proper left side, rather than being centred. It does seem that this has been the original intention at the time of making the object, since an inscribed line is present on all sides of the object, indicating the intended depth of the carving. Furthermore, another shield from the Somers tomb of a similar size and carving has the opposing side “sliced off”. (Plate 4) The reason for this can only be speculated, but it is possible that the objects had a designated space in mind before the carving and the design was altered to accommodate the space without reducing the size of the ornament. It is likely that another element was placed in-between the two stones.

There are multiple tool marks at the back elevation of the stone. Some horizontal inscribed lines and multiple deep, angular cuts - most likely chisel marks or key marks made to roughen the surface for better adhesion to a wall or other support. These together with white, plaster-like substance found at the back of the stone indicate that the object had been fixed onto a wall or support and removed using manual tools. (Plate 9&9.1)

Other marks include a deep hole, possibly from a drill, towards the bottom proper right corner and a rectangular mark at the centre of the bottom edge, possibly from a previous bracket or another kind of fixing. (Plates 9.2&9.3) The stone inside and surrounding the hole has taken a rusty colour - this could potentially be staining from corrosion products, indicating a use of metal fixing in the past (Plate 9.3) The multiple types of marks found on the stone suggest that it had been fitted onto various substrates by different methods over the time.

The front elevation features delicate carvings, multiple layers of paint are present on the shield, however the surrounding stone - the wreath and the base - also seem to be painted or coated, as some remnants of composite materials are present on the surface.

Multiple layers of paint present on the front elevation of the stone. After close inspection under x10 and x20 magnification five different colours have been detected - white, yellow, red, green and purple/blue-grey. The white layer has a fine, smooth surface and visually resembles a lime-wash, however further analysis is needed to determine the chemical composition of the materials used. (Plates 17&18)

Multiple types of composite materials were detected. The stone has been previously repaired, possibly more than once. Materials include fillers and bulking agents as well as potential coatings and metal fittings.

The stone has suffered significant damage in the past, which possibly had caused the stone to separate in three parts - the bottom, top right and top left corners. The top proper right corner and the bottom parts have been reunited, whilst the top left corner is missing. (Plates 22 & 23) The proper left corner was most likely previously built up - large pieces of brick held in a cream colour filling material are still present on the stone bearing evidence of previous fill or an extensive repair. (Plates 26&27)

The crack-line is clearly visible from both the front and back elevations, as well as proper right side elevation. (Plates 22-31) A cementitious material has been used for repair, it has been applied in a crude manner with excess material spreading widely across the surrounding surface of the break. More care has been used to finish the front elevation, however some of the cementing material has made its way through the joint-line and dribbled down the front surface of the stone. (Plate 32)

The parts have been reassembled with little care, creating a slight misalignment, which has resulted with uneven surface and gaps between the parts. (Plates 24,28,29,32) These are relatively small at the front and most have been filled in at the front, however large voids are present at the back of the stone. (Plates 30&31) There are large losses of stone surrounding the crack, but also around the edges of the stone, especially at the back and side elevations. Multiple tool marks at the back suggest that the stone has been separated from its previous support, some of the damage might have been caused at the time, however the rounded and uneven shape of the voids suggest general deterioration of the stone through weathering and handling. (Plates 23 & 31) It is possible that the stone was left in its broken state for some time before reassembly, which might explain the uneven, ill-assorted shape of the break line, especially noticeable at the back elevation. (Plates 30&31)

The incised lines run across the top proper left quarter of the shield. (Plate 41). They are approx 2mm deep and display what looks like an irregular, geometrical pattern. The lines are neat and have an even depth - it seems that they are cut by a tool rather than graffitied free-hand. It is also notable that only Baron Somers’ and his wife’s Martin Ridge’s shields have been marked. Knowing that the Somers family tomb was broken up around the time of the English Civil War (see Chapter 3), it can be speculated that the lines are an act of vandalism, possibly even aimed at Somers family. While this might be an intentional damage, it could also be a mark left on the stone by accident and the cause of these lines remain unclear.

The darkened paint layers seem to be blue or green at a deeper level, it is likely that the pigments forming these paint layers have undergone some transformation which has caused them to darken.

The background displays a pink or reddish hue. It is present across the whole surface of the shield and on the four ribbons, but not on the wreath or the back stone. (Plates 44&44.1) Upon visual examination under magnification it seems to be a ground layer applied above another white or bright yellow ground. In general heraldic colours can be categorised in three groups: metals, furs and colours. Metals refer to noble metals, such as silver and gold and are often represented with yellow paint for gold or white paint for silver. Furs represent animal furs, such as ermine or vair (fur obtained from red squirrels). A pattern of various colours and shapes can be created to represent a specific type of fur. Colours refer to the most frequently used tones in heraldry - blue, green, purple, black and red. (GwynnJones, 1998)

The reddish hue observed on the stone is most likely a ground layer as it is present only on the face of the shield and the four ribbons. However, some stones in Rochester Cathedral have suffered fire damage, turning the stone surface pink or red. (Scott, 2021a) This object is one of a pair and the other stone from Somers tomb (see Chapter 3) also displays that same pink or light red hue. The reddish colour might be an indicator of mineralogical changes caused by exposure to elevated temperatures, which may affect the physical performance and durability of the stone. (Sasinska, 2014) Exposure to fire and high temperatures can cause significant changes in the physical and mineralogical properties of limestone. At high temperatures of 600 to 800°C, the strength of stone is reported to be seriously affected; damage at lower temperatures of 200 to 300°C is mostly restricted to colour changes, including reddening for stones containing iron minerals. (Chakrabarti, 1996)

It is possible that the stone has received a mild exposure to heat, turning some of the stone surface light red and darkening some of the pigments. However the reddish layer might also be a ground layer. These possibilities need to be investigated further to fully understand the nature of the materials present and the extent of damage.

The base and the laurel wreath have a darkened appearance. These elements seem to have been coated, possibly more than once since two different colours are visible - brown and black. (Plates 45&47)

Remnants of a thick white coating are also present on the background surrounding the shield. It consists of multiple layers and seems to be applied above the brown and black coating. (Plate 46) This might indicate that it is a later addition.

The object was examined under UV and Infra-red light. Minuscule samples were taken to determine chemical composition of the materials through FTIR analysis. Cross-section samples were also prepared to establish the stratigraphy of paint layers and learn of the original colour scheme.

The historic paint has been consolidated and cleaned. The object responded to cleaning well and it was possible to remove some of the more deeply ingrained dirt and sulphation crust as well as the surface dust. Through a discussion with the client it was decided to remove the white lime wash as it was not in a good condition and was distracting from reading the shape of the ornament. This also allowed the black coating become more vivid and return some of the contrast between the dark background and the natural light colour of the stone. Remnants of plaster have also been removed to tidy up the appearance and retain the genuine material of the object. The cleaning and removal of undesired materials have improved the legibility of some of the very fine carving and revealed paint layers that were hidden beneath dirt. The removal of cement has improved both the appearance and the physical aspects of the stone as it can now be laid flat on its back with the weight being distributed across the whole of the object. The large crack at the front elevation have been filled in slightly below the surface level and lightly retouched so that the historic damage can still be detected, but is less intrusive when observing the object allowing to appreciate the finely carved heraldic symbols and the object’s history.

Ieva Stradina

City & Guilds London

Acknowledgements and bibliography are contained within the archive report.