Graffiti at St Peter & St Paul, Upper Hardres

/The Church of St Peter and St Paul at Upper Hardres features a considerable collection of historic graffiti, the earliest of which adorns its twelfth-century fabric and may be medieval.

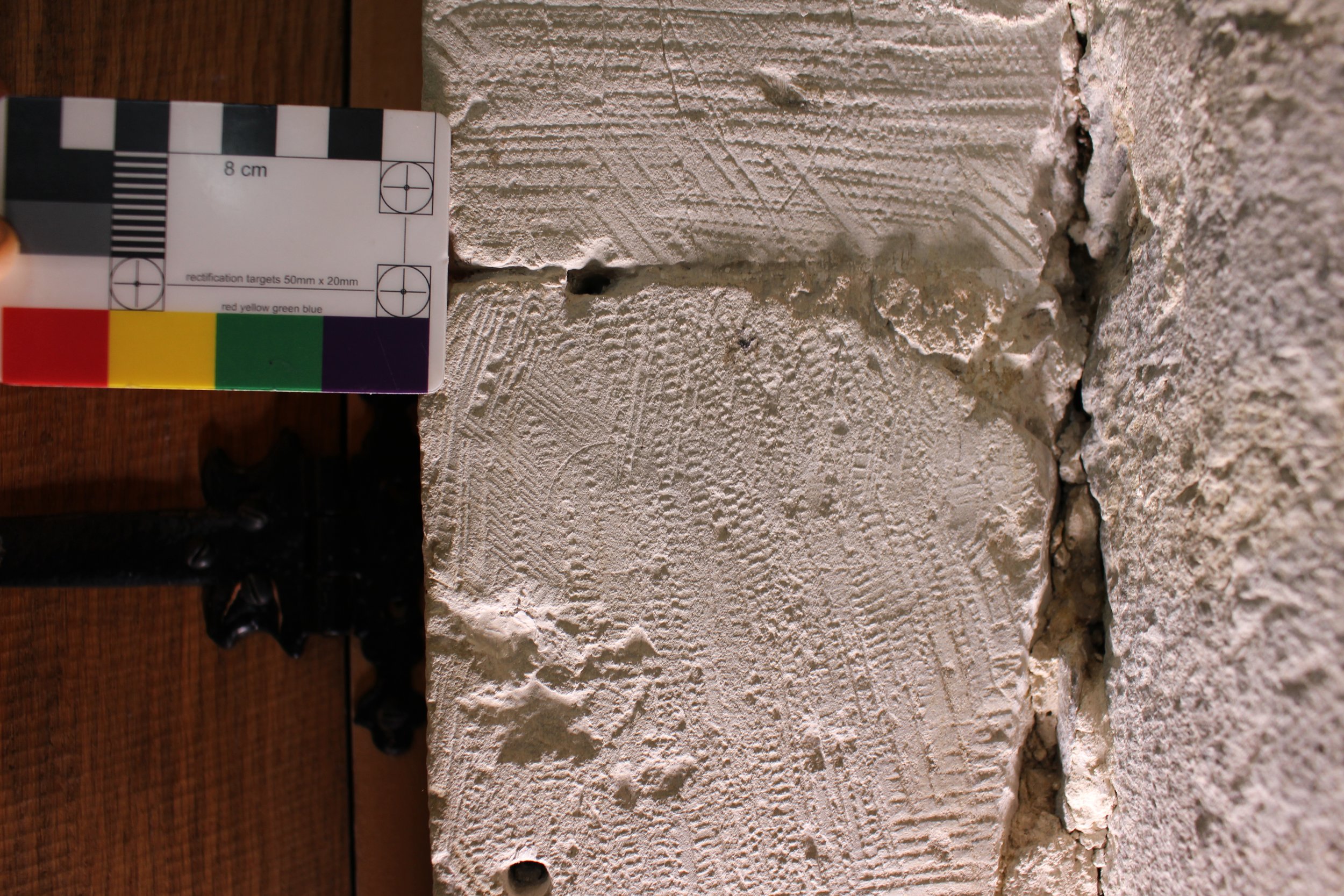

A fine example of a mass dial is located on the exterior of the church. Essentially a vertical sundial, a pencil or straight stick would be inserted into the hole and the shadow correspond to the radial lines at the times for mass during the day.

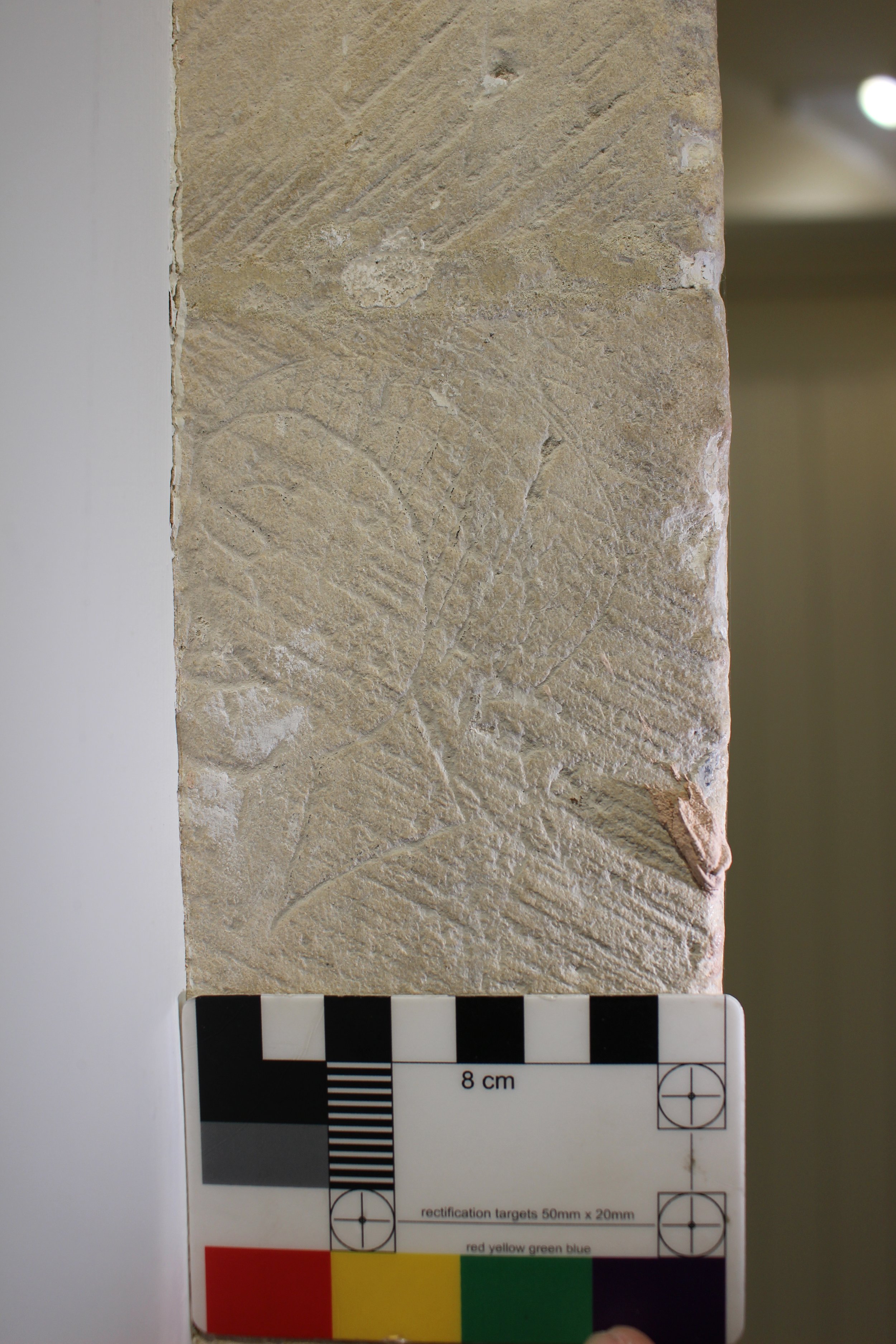

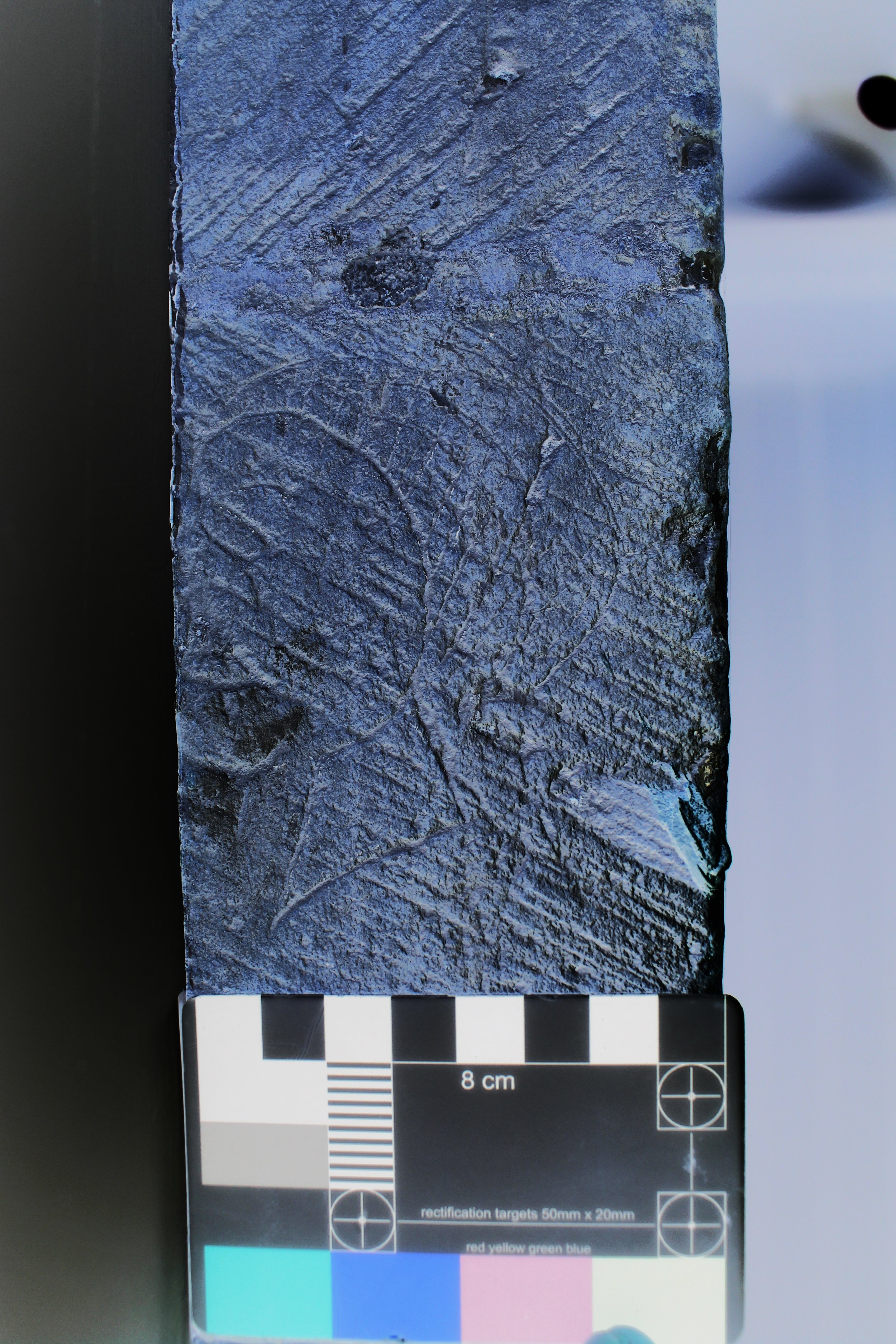

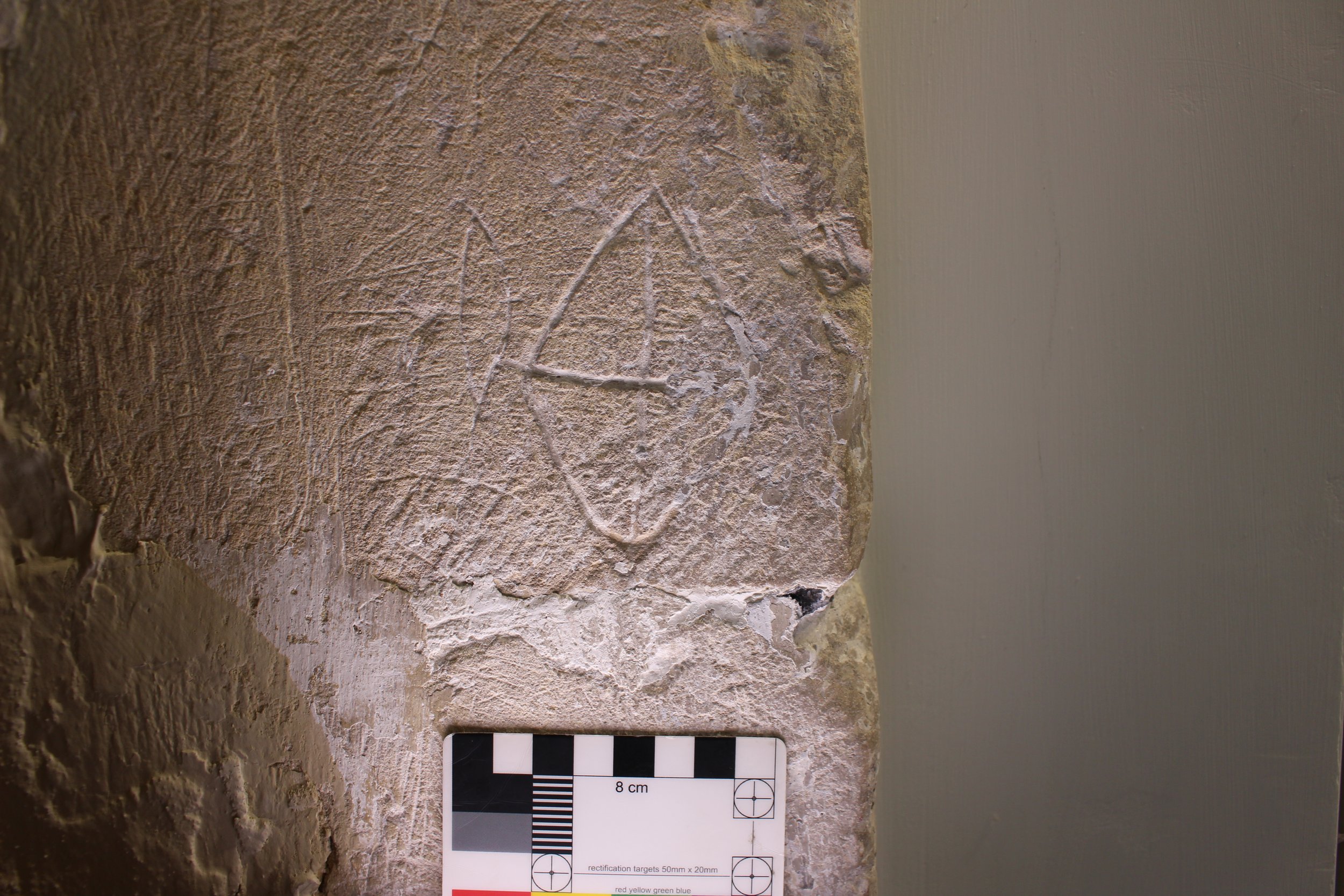

A handful of surviving graffiti within the church are skillfuly executed and well-preserved. A small Christ survives on stonework to the east of the tower.

Christ is identifiable by a halo with hand raised in blessing. Similar designs at Rochester and Canterbury Cathedrals are thought to date from as early as the twelfth century. As at these other sites, this design may have been inspired or copied in miniscule from a medieval icon in the vicinity.

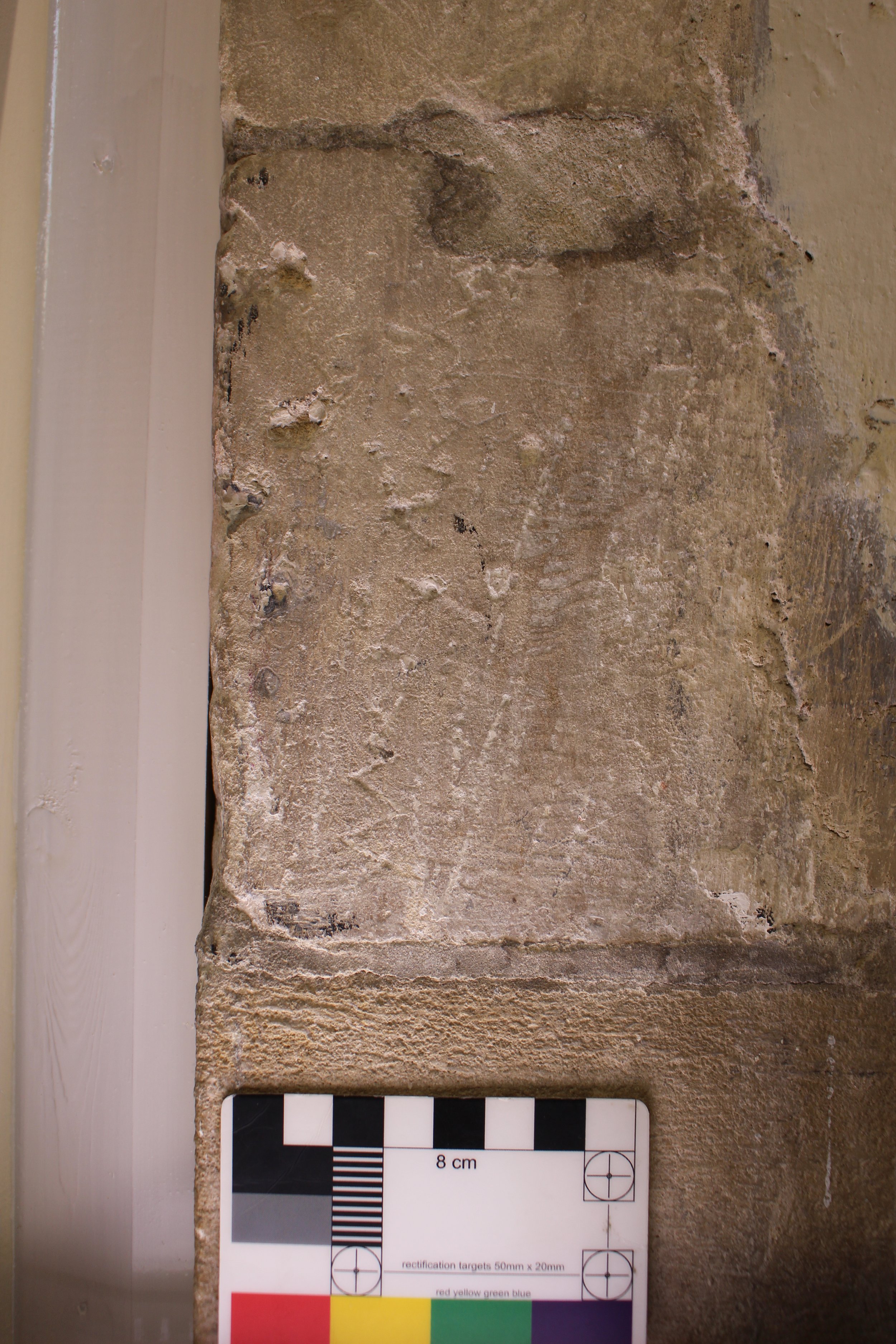

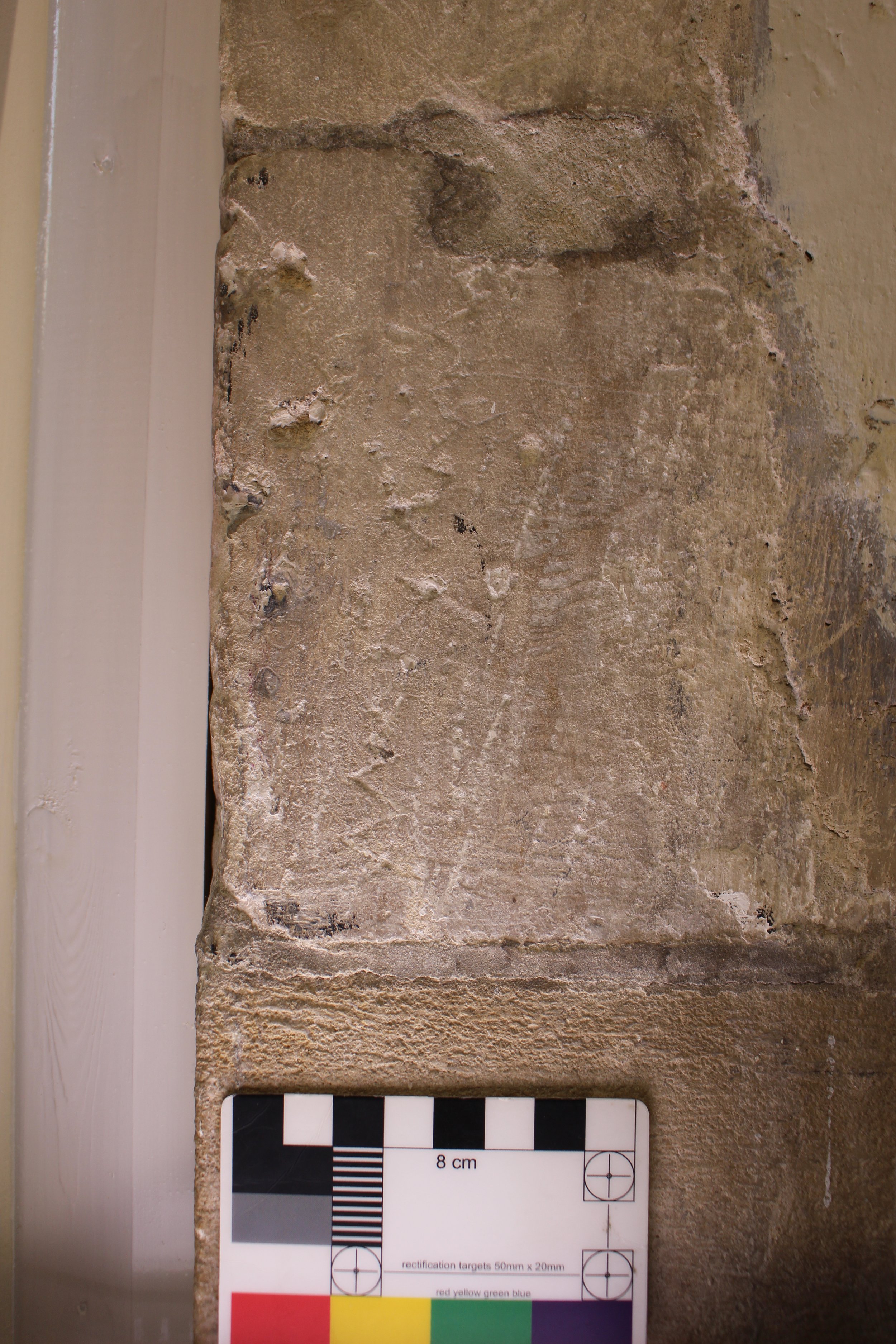

The vast majority of the graffiti at the church is within a cluster around the base of the Norman Tower, previously the site of the medieval font. The cluster gives the impression of having been created during baptismal ceremonies, when this area would have been full of families and small children.

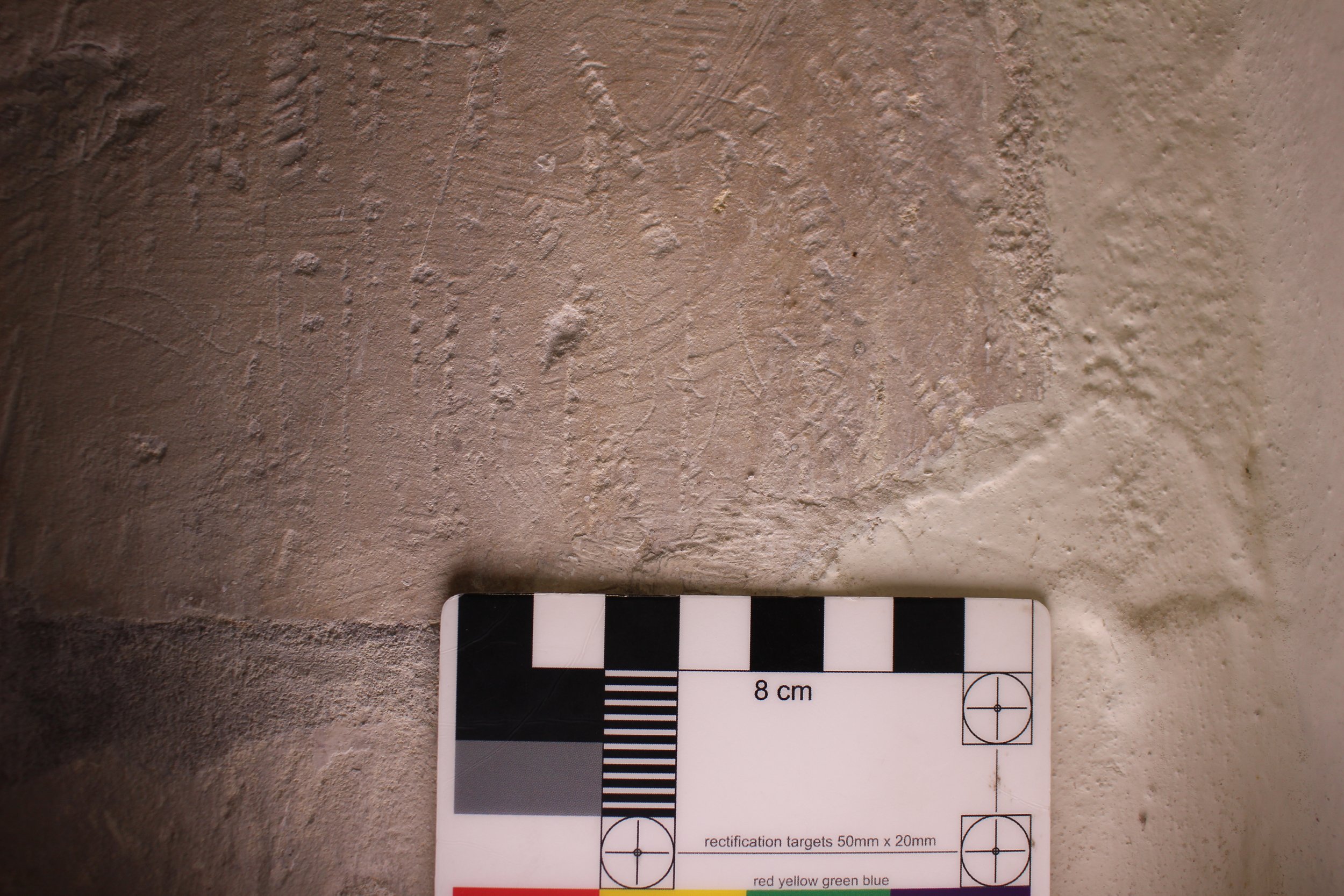

Prsent within the cluster, just two examples are recorded of graffiti produced with a compass-like tool, although more likely a common type of handheld implement that was often kept hanging at the waist (see Matthew Champion’s 2015 Medieval Graffiti: The Lost Voices of England's Churches). Inscriptions comprised of arcs, circles and multifoil designs are some of the most common forms of historic graffiti and are often found around baptism sites, perhaps associated with the warding off of bad luck or spirits.

This profile portrait, possibly of a middle-aged or elderly woman, has preserved the hairstyle and headdress. Cartoonish portraits are not uncommon, although those featuring women are far rarer.

It became common to include a date in inscriptions only towards the end of the fifteenth century, dating previously most often taking the form the number of years into a ruler’s reign. Dating graffiti without a such a reference is very difficult. The date of the construction of the fabric often forms to earliest possible date for an inscription. Occasionally, paint and whitewash campaigns leave evidence in the form of traces remaining within the incisions of an inscription.

A number of crude representations fill an architectural niche at south-west of the tower base, now largely filled with a cupboard. Seemingly produced by children, they are nevertheless demonstrably early, being filled with whitewash which is of an earlier date than the current thin layer of white paint adorning the church.

A significant number of unidentified symbols are also found clustering in this area, though many are vaguely cruciform. The manner of their distrubtion does not suggest they are masons marks, of which the church appears (at least from a ground-level inspection) to be devoid. This indicates the church may have been constructed by one or two masons rather than a large team of banker masons as would be expected at a cathedral or other large site.

What may be a fragmentary ship graffito is located on the north-west corner of the tower base. Another common form of historic graffiti, these were often left in the vicinity of altars and shrines to St Nicholas, the patron saint of those in peril on the sea. At times of trouble during a sea voyage, a vow would be made that if returned safely, an offering would be made to St Nicholas, often taking the form of a ship. There is also a continuing tradition of sailors and sea captions leaving models of ships within local churches to protect their vessel whilst at sea.

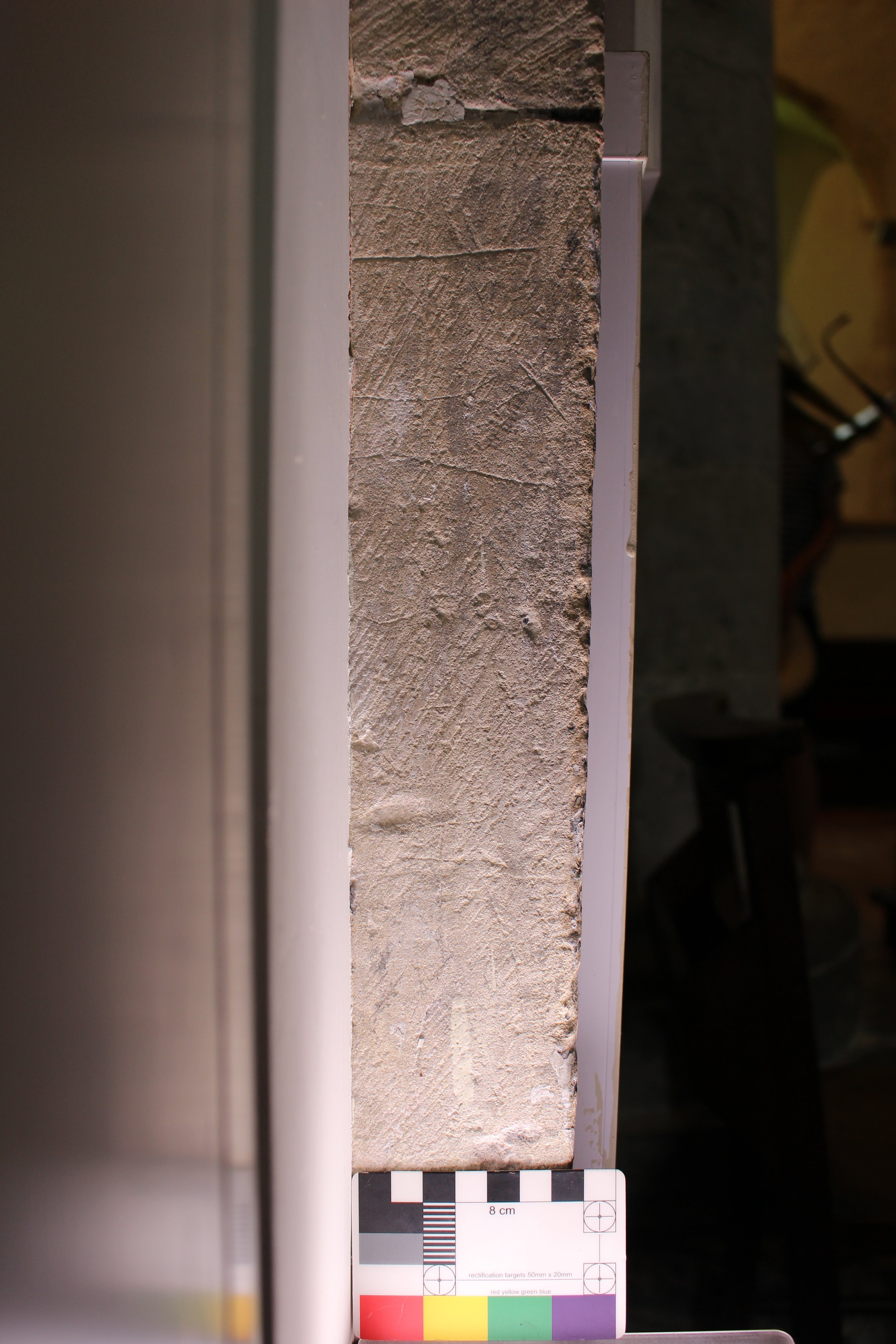

Amongst the symbols and figurative designs present at the church are a small number of text inscriptions. Although largely indecipherable, names are by far the most common form of graffiti and these short inscriptions are likely to be too. Those found at Upper Hardres have a spiky script-like form characteristic of earlier inscriptions created before the widespread use of printed type.

A total of 32 graffiti were recorded at Upper Hardres during a photographic survey conducted on the 13th October 2020 by Jacob Scott of the Rochester Cathedral Graffiti Survey and Research Guild.

The photographic survey is non-invasive and does not require contact with the surface of the stonework, which in many places is fragile. A bright light at an oblique angle to the inscription casts incisions into shadow; a technique known as raking light that considerably aids identification and photography. Digital photographs can be modified and traced in post-production to highlight intricate inscriptions or figurative designs.

Medieval corbel heads adorn the north door and the sanctuary. Much medieval fabric around the church remains in exceptional condition. It may be that early and late modern restorations and replastering have obscured graffiti located elsewhere around the Cathedral.

Find out more about the Rochester Cathedral Graffiti Survey and common types of graffiti identified around Kent and beyond: rochestercathedral.org/graffiti

Jacob Scott

Rochester Cathedral Research Guild

The photographic graffiti survey at Rochester Cathedral begun in 2016 has recorded over 7,000 inscriptions from the 12th to the 21st century.