Archaeology of the Early Norman Cathedral, c. 1080 AD

/Archaeologist Alan Ward discusses the research into the Early Norman Cathedral and reports on excavations in the Crypt confirming its peculiar square east end.

A history of the study of Rochester Cathedral would be a major undertaking, and is beyond the remit of this project. All that is necessary here is to mention a few points from the hundreds of published books and articles. Ii is necessary to go into greater detail in a few instances that are relevant to the archaeological work of 2014-16.

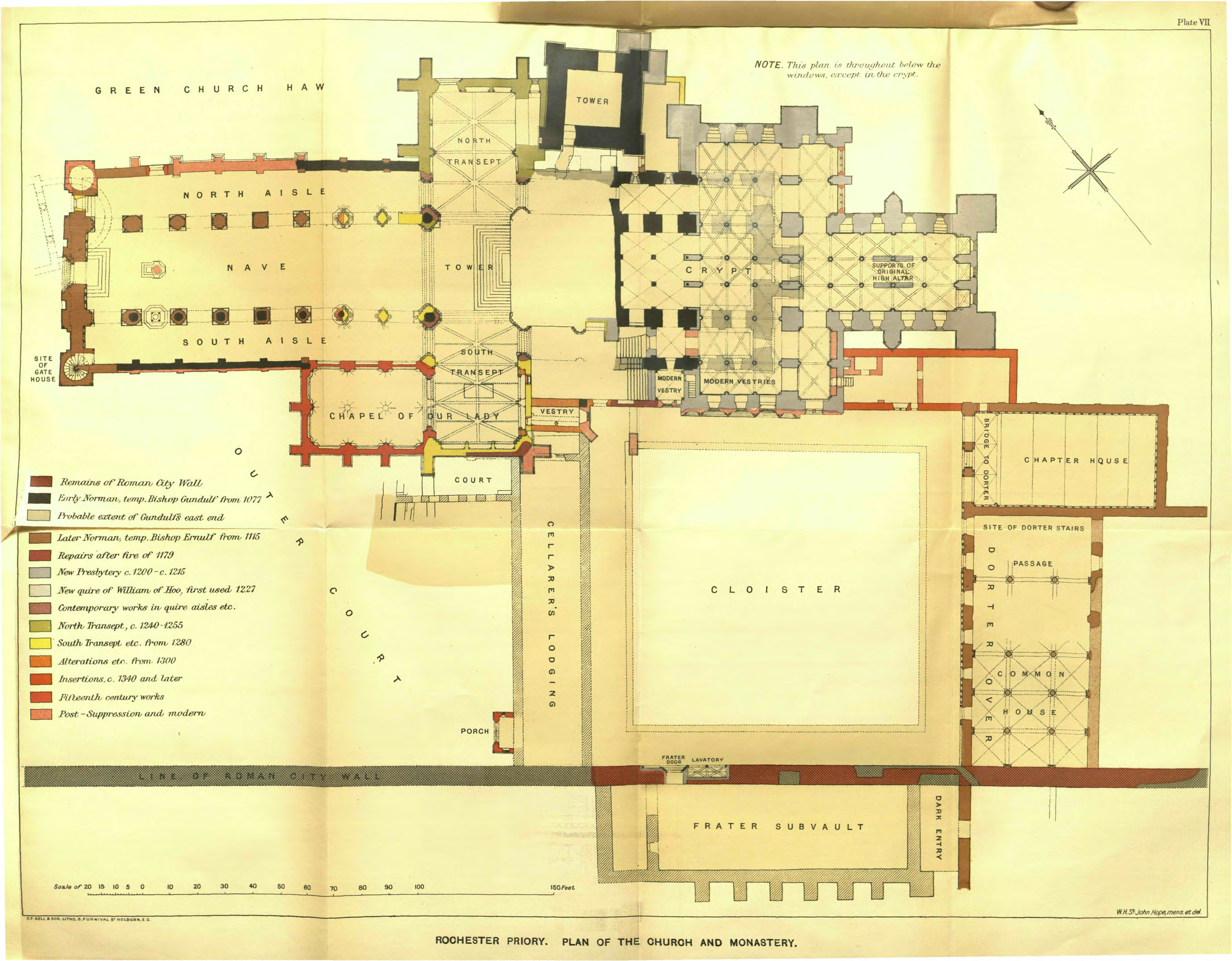

St John Hope’s plan of the medieval Cathedral, with the largely conjectural plan of Gundulf’s remains in black.

There is a brief reference to pre-Norman churches (the plural is important) at Rochester in a late 14th - century manuscript (MS Vit E. xiv) written by William Thorne, a monk of St. Augustine's Abbey, Canterbury. He appears to have taken information from a 13th -century work by another monk, Thomas Sprott (Davis 1934, xx-xxvi). Bede did not refer to multiple churches at Rochester, as he surely would have if they had existed in (or before) his day. The multiple churches could be later than Bede but still pre-Conquest, perhaps referring to the ‘parish’ churches. One is known for certain, St. Mary’s outside the East Gate dating to c 850 (Figure 15) but never mentioned again (Tatton-Brown 1984a, 15; 1988, 222). St Margaret’s and St Clement’s may have been in existence by the mid-11th -century.

For the 12th century we have a few references to building work, but notably none for the rebuilding of the nave in the 1140s or for the east end and transepts from c 1185 onwards, let alone for the supposed rebuildings of east end and nave that were undertaken by Radulf (Flight), Ernulf (Hope) and John (Livett). Little more information for the buildings is given by later medieval writers. Students are left to use archaeological and architectural evidence to assess the development of the cathedral and monastery against this meagre historical background until the 17th century, when more and better documentary evidence becomes available. A Parliamentary Survey of 1649 in the Medway Archives (DRc/Esp 1/1 to 1/5), for example, describes a long (apparently medieval) building to the south of the refectory (Hope 1900, 52, 75; Ward 2002). This document deserves a detailed study, but several structures are mentioned in its precis alone; there could be more regarding the medieval and early post-medieval buildings within the monastic precinct.

3D reconstruction by Jacob Scott of Bishop Gundulf’s Cathedral around the year 1100, with annotations marking unknowns.

Hope, Fairweather and the eastern arm of the Norman cathedral

William St John Hope was one of the foremost scholars of his day, and the two detailed papers he published in 1898 and 1900 are still required reading for any student of Rochester Cathedral – whether they agree with him or not. Many later authors have disagreed with Hope, of course, with regard to the plan form, development and dating of the building’s development. Fairweather (1929) published an early critique, focussing on what he saw as errors in Hope’s plan (and dating) of the Norman and later church. For example, Hope had stated (with no clear evidence) that the Norman transepts were only 15ft (c 4.5m) wide, and from this he deduced that there could not have been a central tower. Fairweather realised that this width was unacceptable and that evidence did exist for a mid-12th - century crossing tower. He did not postulate the existence of a late 11th -century equivalent, but his suggestion that the Norman transepts were wider at least implies it. Even if the early Norman piers were in slightly different positions, they were so spaced that a central tower braced by transepts could have existed in the time of Gundulf.

Fairweather (1929, 188) had ‘always regarded’ Hope’s square-ended plan for the late 11th -century church as being ‘highly unsatisfactory’. He suggested that Hope’s conclusions of were unsubstantiated and that an apsidal church had been constructed (Figures 19-21). Hope’s square end was of later date. These idea were later refined by McAleer and Tatton-Brown (Figure 21). Fairweather (1929, 189) identified three reasons why Hope had rejected an apsidal-ended Norman church: i) Gundulf's ‘local’ and ‘English’ influences; ii) restrictions on the site from earlier structures; and iii) the form of termination of the existing Norman crypt. Hope himself (1886, 325), had classified matters differently: “the considerations influencing this singularity of plan are (1) The existence of earlier structures, (2) The two-fold division of the church onto monastic and parochial. (3) The possession and acquisition of relics”. Hope hardly mentioned (let alone discussed) the last two points, and Fairweather suggested (1929, 189) that they were of no relevance to the plan of the church anyway.

Hope insisted on Rochester’s insular rather than continental influences: “this remarkable plan seems to have been made, as were those of other buildings erected by Gundulf in Kent, on an English rather than foreign model, and it is interesting to find the native idea reasserting itself so early” (Hope 1886, 325). A few years later he wrote “all is abnormal and all is distinctly local, and herein lies the explanation” (Hope 1898, 204). The ‘other buildings’ are not mentioned by Hope and of those known or suspected as being built by Gundulf only St Mary’s Abbey, West Mailing (Figure 22a) is stylistically comparable to (but not on the scale of) the cathedral. It seems certain that St Mary’s did have a squared east end of c 1100 (Ward in prep). The Church of St Gregory, Canterbury (Figure 22b), also has a securely dated squared east end (see Chapter 6). In contrast, apsed east ends exist for the chapels in the White Tower at the Tower of London and the Hospital of St. Bartholomew, Chatham, both associated with (but not necessarily built by) Gundulf. Obviously the most local example available to Gundulf would have been the Anglo-Saxon cathedral, assuming that it was still standing at the time the Norman east end was started. That apsed example, his supposed use of apsidal east ends at Chatham and London, and the Norman tradition of their use all supposedly imply that he would have used one in the new church. But did he?

As for restrictions on the site, the Anglo-Saxon cathedral did not create any space problems for the Norman builders and there was no other building (or at least none that we know of) to constrain the works. Hope thought that the so-called Gundulf’s Tower was earlier than the church, thus creating a constraint on laying out of an east end of normal design (Hope 1898, 201; Fairweather 1928, 192). As Fairweather pointed out, however, this did not mean that the creation of an apsidal east end became impossible: the building simply needed to be moved. Space appears to have been available, as Hope’s plan of the medieval precinct shows (Figure 6). The builders could have laid out the church and cloister parallel to Watling Street rather than the old Roman town wall, although this would have thrown the axis of the church even further to the south from east-west. Alternatively the whole complex could have been skewed to a correct eastern setting, with just enough space for a church of the same length as built in the 13th century (Figure 5).

As Fairweather states (1929, 192), the layout and the limits of the site were those chosen by the builder. He, of course, was pressing the case for an apsidal east end. Neither lack of space nor local building practices had anything to do with the creation of a squared east end. Fairweather was on the way to an explanation, for he pointed out that Gundulf’s mentor Lanfranc (Archbishop of Canterbury 1071-89) paid for the new Rochester Cathedral to be constructed. Canterbury itself had been rebuilt in 1071-7, and part of that work may have been supervised by Gundulf (Plant 2006, 39) – but at both sites Lanfranc was the instigator of this rebuilding. It was he, not Gundulf or the Rochester diocese, who paid for the rebuilding of Rochester Cathedral. This must be the fundamental point.

The east end of Canterbury Cathedral is always regarded as being of apsidal plan, but as recently as 2006 it was stated that the east end of that cathedral had never been fully examined and the only comment from an 1888 excavation was that there was a ‘(doubtfully) apse-like curve’ (Plant 2006, 48). Bearing that comment in mind it is usually assumed that the cathedral at Canterbury was an orthodox early Norman apsidal church. Fairweather argued that this was so and therefore, the church at Rochester would also have been built in the same style. Such an assumption was unsafe, because we now know that Lanfranc did build a square ended church c 1085 in Canterbury. This became St Gregory’ s Priory in the mid-12th century (Figure 22b).

The crypt

Ever since the time of Ashpitel those interested in the architecture and layout of the cathedral had realised that the western, earliest part of the crypt had originally extended further to the east. Two bays of this early structure are extant, and Hope believed there were another two bays which ended in a squared east end with an eastern annex (Figures 18 and 21). This basic design was duplicated above at the level of the presbytery, and was Gundulf’s work of c 1082. Hope’s model, however, was challenged by many during the 20th century. Clapham (1934, 24), for example, suggested that Hope’s interpretation “rests on little or no evidence and is neither reasonable nor probable”. McAleer (1996, 152) states that “in the light of subsequent developments not only in Early English Gothic architecture, but especially at Rochester, [it] appears both implausible and inexplicably precocious”. Flight (1997, 131-141) also questioned Hope’s late 11th century plan.

The east end of the early crypt was found by Ashpitel's probe in 1853. He had expected to find an apse (Plant 2006, 52, note 46), but found a straight wall. Hope believed he had found the chord across the apse, and in 1881 he dug trenches (how many, or their positions, are unknown) and found “a small rectangular chapel, about 6ft 5in long by 9ft wide, which projected from the middle of the front”, with the whole width of the crypt being square-ended (Hope 1898, 204). There was no sign of the apse which he had also expected to find. Hope believed that he had found Gundulf’s east end. His reasons appear to have been based on the tradition of Gundulf’s work at Rochester, the archaic appearance of the work and extensive use of tufa in it, and the apparent absence of any other form of eastern termination. If tufa is reused, it normally has to be reduced in size and irregular shape to rubble rather than ashlar blocks. Most of the tufa in the early part of the crypt is ashlar, whereas it is only present as rubble in later parts of the crypt. Kentish tufa went out of use c 1150, so its widespread presence in the Norman elements crypt is strong dating evidence. As for any other form of eastern termination, Fairweather pointed out that “no exploration has ever been carried out where the proofs of a normal church would be found” (1929, 201). The same point could have been made at any time up to 2014.

Many arguments have been put forward against Hope’s suggestion that the early crypt was Gundulf’s work, especially by Fairweather (1929, 201-4). His first criticism was based on Hope’s plan. Nothing of the sort, he suggested, appeared in England until c 1150. He also examined the building materials. Firestone (now referred to as Reigate Stone) would normally be assigned to the ‘Traditional Period’ (c 1150 at the earliest) in the Medway area (Fairweather 1929, 201), a date with which Mary Berg agrees (Berg and Jones 2009, 50). Fairweather also noted that Reigate stone was also used in Edward the Confessor’s church at Westminster c 1065. Worssam makes no mention of Reigate Stone in the earliest part of the crypt in a 1995 paper (29), but later noted this stone type at the top of pilaster buttresses (2000, 1; 2006, 242). In contrast, Worssam identified the use of Marquise from northern France in the Norman crypt. Its use was largely confined to East Kent and to the very early Norman period, eg the 1080s (its appearance in Rochester could reflect the Lanfranc connection). The supplies were then cut, perhaps due to silting of the estuary from which it was exported (Worssam 1995, 2000, 2006). The petrological evidence as well as architectural detail therefore suggest a date of before 1090 for the construction of the crypt (Plant 2006, 44).

Fairweather and Flight pointed out that Gundulf’s nave and the early crypt have different alignments (Figures 10, 18 to 20). “The axis of the crypt thus diverges southwards from that of Gundulf’s known nave axis. Moreover the south wall of the crypt is laid parallel to the north side of Ernulf’s cloister, distinctly suggesting that it was laid down when the cloister was already a known quantity in design and probably in completion. This suffices for the suggestion that difference of axis predicates difference of date in nave and crypt” (Fairweather 1929, 202-3). “The builders of the Early English presbytery got the east end out of line, and their successors endeavoured to pull all the later additions straight within the new work. Consequently when the centre of the church was reached, the result was clumsy join. The building, therefore, has two axes, one of the Norman church, the other of the later rebuilds” (Flight 1997, 132 quoting Hope 1884, 239). Fairweather’s comment about the cloister can be dismissed because of the HTFE results (see Chapters 4 and 6). As for alignments, there are at least four changes in the nave walls alone (Figure 18). A further alignment exists in what is now the western part of the south aisle wall (Figure 26c). The latter, at the very least, has to be of medieval date, for there was no post-Dissolution rebuilding in this area. This wall was constructed no later than c 1140 and perhaps as early as c 1100. There are also three different alignments in the north wall of the nave, admittedly rebuilt in the western portion. The discrepancy at the far east end in relation to Gundulf’s nave is less than 3ft (c 0.9m). This could be nothing more than a surveying/setting out error. Some of the ‘discrepancies’ may also be because of the age of the surveys being used to assess such matters. The Downland Partnership 3D survey shows that similar variations occur between the late 12th -century re-built crypt and the piers/walls above them as have been suggested for the Norman parts of the crypt. In short, it must be doubtful whether relatively minor differences in alignment have much (or any) significance when determining who built what, and when. Further, even with a change of line between the nave and the crypt, there is no logical reason why the crypt cannot be the earlier element (it would obviously be built before anything else was erected on top of it, after all – and it needs to be stressed that the western arm never seems to have had a crypt).

Alexander (2006, 149) noted that “the southward deviation [of the piers] does not continue into the choir and it can only have been connected with the need for an aligned crossing”. In a footnote she also states that “the divergence of the nave south arcade was noted by Fairweather, but interpreted as part of an elaborate realignment of the choir and its crypt, and his theory has not been widely accepted” (ibid, note 4).

A difference in axis between the nave and the crypt does not necessarily mean a difference in date. The large abbey church of St Peter at Whitby has an east end diverging by 3.75m southwards from the line of the north wall of the nave (Clapham 1952, plan). Here the deviation occurred over a length of 90m (250ft) and must have been visible within the building. It probably would not at Rochester. At St Edmundsbury Abbey (Suffolk) the north-east crossing pier is about 4ft (1.3m) out of alignment with the north-west pier and those of the north aisle of the nave, but in alignment with the piers in the presbytery (Whittingham 1971 plan). A line drawn down the centre of the northern crossing piers, as at Rochester, is not parallel to the line drawn down the centre of the southern crossing piers. This takes place in a church nearly 500 feet long, twice the size of Rochester. At St Edmundsbury it is notable that the presbytery walls are offset inwards from the nave by about the same measurement as the walls at Rochester are offset outwards. The changes of alignment in these churches do not seem to have been interpreted as the result of major rebuilds. The walls in question for each building are of one (but quite possibly long) structural phase. At both churches building began, as was normal practice, at the east end (Clapham 1952, 14; Whittingham 1971, 13).

It might be argued that the area where the termination of a shorter 11th -century church would lie has never been explored. Two projects have now been undertaken in that area, one in 1999 (Ward 1999) and HTFE in 2014-16. In neither project was there any indication of an earlier east end under or to the sides of the Norman bays. It could be argued that the excavation of this crypt had destroyed any earlier structure, but that is implausible: in situ Roman and Anglo-Saxon features have been found (in some areas with intact stratigraphy above them - see Chapter 4), but no earlier foundations.

McAleer suggested that the standing masonry contained evidence for an earlier apse. Describing the junction between the early crypt and its late 12th -century successor, he states that “at the this point there are no signs of Romanesque pilaster responds on the aisle sides of the remaining easternmost pair of piers as there are on the piers at the west” (McAleer 1999, 36). This is simply because the pier sides in question had been cut back and/or refaced at the time of the late 12th -century alterations. He continues: “the existing responds are Gothic from the ground up to their abaci, which are set at a higher level than the Romanesque respond imposts. Yet the vault that springs from them is the original Romanesque groin vault of this bay. The absence of Romanesque responds at the east end of the aisles suggests that the aisles may originally have ended at this point in semi-circular apses, rather than continuing with one or more bays with piers identical to those at the west”. In fact the east part of the groin vault had also been altered in the late 12th century, and the original fabric was removed; the Romanesque abaci had to be re-set when this was done. The embedded capitals in the central piers show that there had to be standing shafts between which, in turn, establishes the former existence of at least one more bay to the east (Plant 2006, 47).

Fairweather admitted (1929, 206) that ‘destructive criticism’ of Irvine and Hope’s interpretations needed to be replaced with constructive arguments for his idea that there was an apsed east end of late 11th -century date. He believed that Gundulf planned and completed an apsidal church, with a cloister to the south of the nave. It was shorter than the square-ended church found by Hope and had a central apse with flanking apsed chapels. Ernulf demolished the early cloister and constructed a new one to the east of the South Transept. He suggested that this cloister diverged slightly to the south of Gundulf’s, but did not present evidence for this. According to Fairweather Ernulf probably intended to follow this by the erection of a new presbytery parallel to the new cloister, which involved the widening of the crossing and a change in angle southwards of the two eastern bays of the nave to accomplish this. Fairweather suggested that this work was partially completed and survives now in the western bays of the crypt. He also agreed that the standing wall of the three eastern bays of the nave north aisle were also Ernulf’s. Supposedly the work was only half-heartedly carried on by his successor John (1125-37), and to be completed after the fire of 1137. The foundation in the crypt that was found by Ashpitel and Hope might cover the earlier foundation of Ernulf.

One would hope there would be some mention of all this work in the historical sources. There is a document, after all, confirming that Ernulf rebuilt the dormitory, Chapter House and refectory. It is difficult to believe that the rebuilding of those structures would be mentioned while the rebuilding of the more important east end and nave would not.

Irvine’s tunnel

James Thomas Irvine was the clerk of works for the architect George Scott from 1874-6 (Flight 1997, 125). His work under the South Transept has already been noted. Late in 1874 he dug a tunnel below the floor of the quire westwards of the crypt to insert the wind trunking for the organ bellows (Flight 1997, 126. His section drawing of the north side of this c 10m long tunnel below the quire floor was published by Hope in 1886. The original of this drawing, and one of the south side of the tunnel, are amongst the Irvine Collection of documents housed in the Medway Archive Office. Annotated versions of his sections (and Hope’s version) have been published (Ward 2014b) and are reproduced here at a larger scale (Figures 14a-b) with Hope’s (Figure 14c).

The tunnel extended from the west wall of the crypt for virtually the whole length of the quire. Two vertical shafts were dug through the latter’s floor down to the tunnel to allow debris to be removed. Irvine drew the stratigraphy that he saw and noted at least three floors, the lowest of which he regarded as being of the time of Gundulf. He regarded this floor as being contemporary with the west wall of the crypt, which cut the soils below the floor. At the west end of the tunnel, he found what is usually regarded as Gundulf’s sleeper foundation binding the eastern piers of the crossing. This rubble foundation was at least 1.5m wide seems to have been sealed by chalk concrete passing beyond its eastern edge by c 1.75m. At the east end of the tunnel this floor (forming the roof of his tunnel) met the west wall of the crypt. Irvine ‘carefully examined the junction’, and thought that wall and floor were contemporary. Flight disputed the contemporaneity and suggested that the wall cut the floor. In either case, the crypt would have to be later than the sleeper foundation. If that was dated to the time of Gundulf, it follows that the crypt had to be later. It is possible, of course, that Irvine omitted details and/or made mistakes in his recording. The conditions he was working in must be taken into consideration: a narrow tunnel no more than c 1.5m high with no shuttering and poor lighting. As luck would have it, HTFE unexpectedly provided an opportunity to re-examine the east end of his tunnel.

The Norman Crypt

The western part of the crypt (Figure 42) has long been recognised as being earlier in date than the minor transept (cross-hall) crypt and St Ithamar's Chapel. This early crypt measured approximately 22m externally x 19.50m (from the inside face of the west wall to the outside face of the eastern annex). The standing two bays of the early crypt are divided into three portions. A north aisle is separated from the central space by large piers (see Plate 11). The central area is, in turn, divided by two shafts made from Marquise Stone (Worssam 2000, 1 – see Plate 12), and separated from a south aisle by further large piers. Of the four large piers of this early structure that survive, two are complete and two were partly refaced in the late 12th -century alterations. Two intact half piers attached to the west wall face into the central space. These and the curved quarter-columns in all the wall corners are made primarily from tufa blocks. The two eastern piers have capitals of the early crypt surviving, but embedded within late 12th -century refacing: they demonstrate that further free-standing shafts had existed to the east, and hence that the crypt was at least one bay longer originally (McAleer 1996, 151). The sleeper wall for the northern piers was found in the HTFE excavations, but unsurprisingly neither the piers nor any sign of the missing shafts was seen: they had been removed completely in the 12th century. The sleeper wall on the south was not exposed, because not all of the 19th -century rubble was removed in this area. Nevertheless, the overall length between the surviving west end of the early crypt and the east wall found in the 2014-16 project shows that Ashpitel and Hope were correct in their conclusions with regard to the original number of bays in the Norman east end.

The face of the west wall of the crypt is made mainly from Ragstone rubble, with some tufa rubble and rare flint nodules. In places what may be original render still survives. The core is made almost entirely of angular flints. Fragments of Roman tile were noticeable by their absence from both wall face and core (the latter having been exposed when Irvine’s tunnel was re-opened). No Caen Stone was used in the early part of the crypt or, more correctly, there was none surviving in the visible upstanding parts. What was believed to have been Caen Stone rubble was found in the north wall foundation, but this may have been a mistaken ascription caused by staining. Other than that, the stone does not appear to be present in the identified parts of the first Norman church. This suggests that this material was not yet being brought up to Rochester from Canterbury in any quantity.

The excavated (eastern) portion of the Norman crypt

The outer walls of the Norman crypt lay c 3m inside the standing north and south walls of the late 12th -century building, the walls of which largely survive intact (Figure 42). The east wall of the Norman building was found c 1m to the west of the screen division between the main cross-hall and St Ithamar’s Chapel. In the 2014-16 work, the foundations of the north and south wall of the earlier crypt were revealed for much of their length. Although there was some variation, these foundations were c 2.2m wide.

The north foundation (wall 684) was initially revealed for a length of 3.5m. The uppermost portion of the foundation overlapped its construction cut internally by c 0.3m (Figures 34b, 34e and 42). This overlap did not occur in the more limited exposures of the southern foundation (wall 860). Either this shows a difference in the way the two foundations were laid or a greater reduction of the southern Hidden Treasures at Rochester Cathedral: Archaeological Investigations 2011-2017 52 area in the late 12th century or subsequently (Figure 43a). Certainly there were distinct differences between the two foundations, as well as with that of the east wall. The north foundation (684) was over 0.65m deep (its base was not seen - Plate 20) and consisted of loose flints in the lower portion, with a mix of flints, small fragments of Ragstone and chalk rubble in a fine sandy buff mortar for the uppermost 0.2m (Figures 43b and 43c). One would normally assume that the mortar would have been poured as a liquid slurry into the foundation trench, but its soft nature may indicate that the upper materials were placed into the trench in a dry state and then compacted down. The small rubble content was reminiscent of finely sorted demolition material, perhaps from the Anglo-Saxon cathedral or a Roman source. The lower material consisted entirely of angular flint, largely unmortared and thus with voids between the nodules. At its east end the southern foundation, consisting of crushed mortar with fragmented tufa and chalk, was only c 0.45m in depth. At its west end where it joined with the east wall it was considerably deeper, c 0.65m (but again the base was not reached).

Plate 20: The north wall foundation of the Norman crypt was re-used as the sleeper footing for the piers of its late 12th -century replacement (the timber protection for one of the piers can be seen here). The two vertical scales (1m and 50cm) rest against the face of the Norman foundation (684). The chalk (785) in front of the foundation is a remnant of a medieval (possibly late 12th -century) floor butting against 684.

The east wall of the Norman crypt ran in a straight line between the east ends of the north and south walls, without any trace of a deviation or extension to the east except in its centre, where the small square chamber noted buy Hope was found (see below). The west (inner) edge of the eastern wall’s foundation was exposed along virtually the whole of its length, while the east edge was seen to the south of the central chamber (it was obscured by the foundations of the Ithamar Chapel to the north of this). It was between 2.3m-2.5m wide. The construction trench for the east wall also varied in depth along its course from 0.4m in the northern part (foundation 729, wall 720) to over 0.7m deep (foundation 721, wall 719) just to the south of the eastern annex, where a distinct junction between the shallower and deeper portions was seen. The base of the deeper portion, infilled with loose flints, was not exposed. One of Hope’s trial trenches evidently existed at this point, because mixed material Hidden Treasures at Rochester Cathedral: Archaeological Investigations 2011-2017 53 including brick fragments was seen at the top of this loose material, this was partly emptied but so that the Norman footings could be recorded (Plate 21).

Plate 21: The east foundation of the Norman crypt, looking north-east with the piers at the entrance to the late 12th -century Ithamar Chapel beyond. The 50cm scale is on the east edge of the Norman foundations: the footings for the late 12th -century piers had been built close up to the earlier ones. The 1m scale rests on the south wall of the small chamber on the east side of the Norman east wall. The ‘cut’ through the east wall evident here must be one of Hope’s trial trenches.

Why these differences in foundation depths occurred is not known. There was nothing obvious in the apparent ground conditions (such as areas of pit fill or variations in the Brickearth) that would explain it. The variation may have come about through nothing more than the operation of different labour gangs.

The eastern ‘annex’ first found by Hope was uncovered in the centre of the east wall (Figures 47-9; Plates 21-2). The south face of the south wall (724) was revealed and, impressively, the lowest course of masonry was still in place (Figures 47-8 and 49b), its flint core faced with ragstone blocks. Most of the north (Wall 753) and south walls were covered by large late 12th -century piers at the entrance to the Ithamar Chapel, which hid full width of the Norman work, but each was in the region of 1.6m wide. The east wall foundation was slightly wider at 1.8m. Here both east and west faces were revealed on either side of the modern glass screen (which had been left in place). Again loose flints (756) formed the lower portion of this foundation with mortar above. Within St Ithamar’s Chapel the north end of the annex east wall was visible, turning to the west, and the south-east corner was also seen (Figures 47 and 49d). This showed that the eastern annex was 5.5m wide (ie north-south) externally and c 2.2m internally.

Plate 22: The south face of wall 724, with the dressed blocks showing that this was originally standing fabric. The foundations can be seen where one stone had been removed in antiquity. One of the late 12th -century piers at the entrance to the Ithamar Chapel had been built directly onto the Norman wall, though a small area of new footing was needed on its north side.

Another of Hope’s trial trenches was found cutting through the remains of the Norman crypt’s east wall and that of the annex (Figures 47, 49c and 49e; Plate 23). Its west end started between two of the late 12th -century piers and continued east through the centre of the annex, cutting through its east wall and continuing eastwards for an unknown length. Tatton-Brown’s 1994 trial trench had cut into the east end of Hope’s, and had also exposed the east wall of the Norman annex (Figures 38b and 47). In 2006 Plant stated that ‘an excavation in the eastern crypt in the 1990s failed to recover the eastern extremity of St. John Hope's eastern chapel, as it should have done if his plans had been accurate...’ (Plant 2006, 52, note 49). Given the small size of the 1994 excavation, it is not surprising that the Norman foundation was not recognised. The composition of the 11th -century footing and the adjacent one under the late 12th -century pier was very similar, and the complete excavation carried out in 2014-15 was necessary to elucidate the relationship between them.

This trench is the only one that Hope describes in any detail (1900, 84-5). He found the remains of a timber box and a skeleton. The box was found ‘buried with its lid just level with the eastern floor’, but it ‘was not noticed until it had all been broken up and nothing could be made from it’. The remains (and the skeleton) were reburied. Pieces of timber were indeed found in the backfill of Hope’s trench, along with some human bone (SK 1), including long bones and the skull (Plate 23). These are discussed in Chapter 6.

Plate 23: Hope’s trial trench through the centre of the eastern annex re-excavated in December 2014. The long bones and skull were recovered later, when the area under the modern threshold at the entrance to St Ithamar’s Chapel was excavated.

A buttress/foundation (1803) extended nearly 2m to the south of the junction between the south and east walls (Figure 42). This consisted of loose mortar with chalk rubble in its upper 0.4m, beneath which the material became more compact. Its base was not seen. Part of a standing Ragstone wall (698) for this buttress still survived with a good southern face set c.1m back (north) from the edge of the foundation.

Plate 24: The south-east corner of the Norman foundations and buttress 1803 during initial cleaning. The straight edge of the south wall can be seen passing under the modern pipe.

A buttress was expected at the corresponding north-east corner, but a very different structure was found instead (Figures 44-46; Plates 20 and 25-7). This consisted of walls 840 and 842, 2.1m apart (measured from their inner edges) and extending up to 2.65m to the north (at which point they were cut by the north wall of the late 12th -century crypt). Walls 840 and 842 were 0.65m and 0.45m wide respectively. The eastern wall (842) had been first been seen in 2012’s test pit 8, when it was thought to be of Roman date. The wall had been separated from the northern foundation (684) of the 11th - century crypt by a grave cut (825), there was no reason to believe that 842 and the crypt wall were anything other than contemporary. They were at the same physical level, and wall 842 had no other structure with which it could be associated. Wall 840, running parallel to its west, was bonded with 684 and these foundations are therefore certainly coeval (Figures 35b and 45a). Both of the walls were trench-built and well-constructed (if anything, better than the main foundation). They were made mainly from small flints bonded by poured mortar – fully to the base of 840, and onto a layer of unmortared small flints in 842 (but these were tightly packed and compacted).

Plate 25: Walls 840 (in the foreground) and 842 (under the rear right scale), with the path of re-set ledger stones separating them. The north foundation of the Norman crypt is to the right, thickened at the east end (ie the north-east corner), perhaps to support a pilaster buttress. View looking east.

It seems unlikely that this structure had continued much further to the north, and it is probable that its north wall has been destroyed by the construction of the late 12th -century crypt’s north wall. This room is referred to as the northern annex to distinguish it from the eastern one seen by Hope (who evidently did not expose these walls). Much of the interior of this annex was hidden by a ledger slab path (852), which was left in place. Excavation of a narrow trench to the north of the ledgers, however, uncovered not only the two shorter sections of walls 840 and 842, but also a chalk raft (829/830) in between. Smaller areas of this raft were also seen to the south of the ledger path. Presumably it was upon this raft the floor of the room would had been constructed. It is possible that mortar layer 833 formed the floor, but this did not spread over the whole area.

Plate 26: Top - wall 842 cut by grave 825, with part of raft 829/830 to the north (left). Bottom – wall 840, clearly bonded to the north wall foundation 684.

If there was a door from the annex into the Norman crypt (it is difficult to believe there was not), it was probably in the south-west corner. The 0.8m length of wall 684 to the west of the thickened east end (pilaster buttress? – see Figure 44 and Plate 25) up to the inner (east) face of 840 would be just wide enough for a door. Alternatively the thickened corner might have contained a spiral stair up to the presbytery level, in which case a door set at forty-five degrees to the alignment of the crypt in the base of this turret could have been the entry and exit point.

Two flint deposits (872 and 871) were observed on the east side of Wall 842. The lower (872) was the better preserved and may have been created as an external yard surface when the annex was built. The upper deposit had probably been laid at some time in the 12th century before the Norman crypt was demolished (Figures 45e and 45f).

No floors of the early Norman crypt survived within the area defined by its foundations. The late 12th - century rebuilding had removed virtually all trace of the standing masonry of its predecessor, except in a few very limited areas (such as the eastern annex) where a course or two could be incorporated in the footings of the new work. The thorough levelling of the old fabric evidently extended to the complete removal of the earlier floors. The only layer which might be connected with the demolition was a compacted black soil (context 777) across part of sleeper foundation context 776. This had the appearance of ‘trample’ from the footfall of labourers working on the late 12th -century rebuild.

The standing (western) portion of the Norman crypt and Irvine's tunnel

The fires of 1137 and 1179 not only damaged the Norman east end (and allowed the new design to be built after 1179), but also presumably damaged or weakened the earlier crypt. The great rebuilding would probably have required its partial demolition anyway, and the only surprise is that anything was left at all. The rebuilding seems to have begun earlier than Hope (among others) thought, and that either Walter (Bishop 1148-82), Waleran (Bishop 1182-4) or Gilbert (Bishop 1185-1214) began the process and decided to update the design, perhaps to ‘keep up’ with new work undertaken at Canterbury. The retention of the western portion of the crypt suggeststhat fire damage did not extend this far west, either at crypt or cathedral floor level. The two western bays of the Norman crypt therefore survived at least in part because elements of the 11th/early 12th -century fabric above were retained as well. Just as with the excavated eastern part of the Norman crypt no sign of ash, fire damage, or demolition debris of the earlier structure was identified in the standing bays of the Norman crypt during the work of 2014-16.

In 2014 the modern concrete and brick floor over the whole area of the Norman crypt was removed. Hope is silent as to what he found in this area during his 1881 excavation trenching. When the new organ blower pipe and an electricity cable were inserted in 1999, however, a series of post-medieval earth floors was seen along with a mortar foundation up against the north wall. This foundation was not bonded with the wall and at first it was thought it might be evidence for an apse (Ward 1999, 4, figure 7 section A-B in that report and redrawn here as Figure 24), but although there was variation in width there was no trace of a curve/arc. It may have represented the base of a stone bench of Norman or later date. A similar stratigraphic relationship and variation in width for a definite bench was found within the vestry (see below page). The 2014-16 work saw the whole of the north aisle of the Norman crypt exposed and post-medieval earth floors were again uncovered. The lowest floor was regarded as being of medieval date. This was a sandy brown mortar (641) which had probably been poured as a slurry. There was no sign of tile or stone slab imprints and the degree of wear it had suffered hints that this was the actual floor surface. Admittedly any tile imprints could have been destroyed had such a floor been removed, but the absence of tile fragments in this area may suggest that no such floor had ever been laid. This area of mortar may have been the one extensive area of Norman date flooring to survive. Chalky plaster floor patches (646), as already found to the east, may be the late 12th -century surface (see below).

During the final months of the project a 2.5m length of Irvine’s tunnel was re-opened (Figures 32-3, and 51-2: Plates 27-8) so that the organ blower pipe could be reconfigured, in turn allowing removal Hidden Treasures at Rochester Cathedral: Archaeological Investigations 2011-2017 59 of the cabinet built to house (and hide) it in 1999. The Roman soils and pits found within this short length of the reopened tunnel (Plate 12) were sealed by a 0.35m-thick grey-brown soil (1224) similar to ‘dark earth’. A sherd of early medieval pottery (Torksey Ware) datable to the 8 th/9th centuries can be regarded as coming from this deposit, and the layer can safely be regarded as Anglo-Saxon soil.

Plate 27: Left – the south face of Irvine’s tunnel re-opened. The dark earth and Roman soils can be seen behind the lower (white) portion of the 1m scale, with the made ground behind the red upper part – the sloping tip lines can be seen to the right. Note the rough rear (west) face of the crypt wall to the left. Right – the north side of the tunnel with mortar and flint floor 1221, and the crypt wall to the right. The shadows cast by the arc light clearly show that the floor both abuts and slightly overlaps with the wall.

There was no sign of differentiation in mortar colour or materials used within the whole height of the west wall within the re-opened tunnel. Its hidden west face was ‘rough’, as Irvine had described it. There had been no attempt to create a neat face (Plate 27). The lowest 1.45m portion of the wall was trench-built into the Roman and Anglo-Saxon soil layers. When first built, the masonry above this would have been free-standing – but it was not meant to be seen, and indeed would soon be covered up. A series of layers ranging from off-white coarse mortar to grey silty soil was revealed for a thickness of 1.1m (Figures 51 and 52; Plate 27, left) over the dark earth layer (1224). These layers are interpreted as a series of tip lines formed rapidly, and hence only one context number (1272) was given. The very lowest of these deposits had several fragments of Roman tile within it. No other dating material was found. Irvine had described these deposits as made-ground (see above). The material was quite loose and, as depicted by Irvine, sloped up to the west face of the crypt west wall (Figures 14, 51b and 52b).

Two distinct thickenings or ‘corbels’ could be seen in the rough face of the wall’s upper 1.2m on the north side of the tunnel (Figures 52a and 52b). They were less clear/regular on the south side (Figures 51a and 51b). A floor of hard shelly off-white mortar with angular flints and rounded brown gravel (1221) butted against the west face of the west wall, and lipped over the ‘corbels’; it also sealed the tip layers (1272). This floor had been strong enough to form the roof of Irvine’s tunnel in 1874 (Plates 26-27, 29), but additional timber supports were inserted in 2016 as a precaution. In strict stratigraphic terms the floor post-dates the wall, but in reality they can be seen as contemporary. Certainly the wall did not cut the floor – there would have been a distinct scar in the hard flint and mortar if it had done.

Plate 28: Mortar and flint floor 1221 formed the roof of Irvine’s tunnel. The rough underside of the poured surface is very evident here. The small hole referred to in the following paragraph can be seen starting to open up to the right of the trench shore closest to the crypt wall.

Fortuitously, it was possible to observe a small amount of stratigraphy above floor 1221. The vibration of the drilling machinery used to cut back the ceramic organ blower pipe and compacted Roman soils created a small void at the point where the floor met the wall (Figures 51c and 52c). As drilling proceeded this void became wider and higher, eventually measuring nearly 0.1m in diameter and 0.3m high. Floor 1221 was found to be 0.1m thick, and above this loose Caen stone and chalk rubble with mortar lumps (1232) could be seen for a 0.2m thickness. At the top of this material the underside of a further solid mortar surface (1233) could be seen – probably a later floor, as described by Irvine. The loose stone material between the floors extended 0.2m eastwards over the corbelled wall face. At that point solid material was encountered, but it was impossible to tell whether this was the wall face (which seems likely) or rubble. This appears to show that the west face of the wall has an offset of 0.2m immediately above floor 1221, which overlapped the wall face by c 20mm. This offset was covered by the loose stone material and the upper solid mortar.

The Norman stair in the lift shaft

A new access lift was to be built at the top of the Kent Steps in the South Quire Aisle. This would descend into a small side-crypt off the south side of the landing at the bottom of the stairs down from the South Quire Aisle into the main crypt. This side room had been built as Hidden Treasures at Rochester Cathedral: Archaeological Investigations 2011-2017 61 part of the late 12th -century rebuilding of the eastern arm and crypt, but in 2014 it had been in use as the cleaners’ store for some years, and was still fitted out with shelving on its east and west walls. On the former side, the shelves were known to hide a doorway to a mural passage and stairs up to the lesser south-east transept; this staircase had been blocked up in the later 18th century in an attempt to counteract outward movement of the transept wall. The shelves also obscured the original bases and capitals of attached colonette shafts in the four corners of the room. The exposure of all these features when the room was cleared out by the contractor at the beginning of the HTFE works was welcome, and allowed the chamber to be fully recorded before work began on the lift shaft (Plate 29).

Plate 29: The east wall of the side-crypt (former cleaner’s store) cleared of shelving in August 2014. The door to the mural passage and (blocked) stairs and the remnants of the engaged colonette shafts were exposed as expected.

Work then proceeded on the lift shaft itself. This would start on the uppermost treads of the Kent Steps and descend into the south-west corner of the side-crypt, butting away part of its west wall and the late 18th -century vaulted ceiling in the process. All of this work had been approved in full, subject to the conditions mentioned in Chapter 1: any harm caused by loss of exiting fabric was substantially outweighed by the benefits of inclusive access. The lift was on the critical path of the contract as a whole, so work started on it in September 2014. At this point no investigation under the Kent Steps had been possible because the existing chair lift had been kept operational until the last possible moment; similarly the side-crypt had only just been cleared of its stores shelving. Therefore all parties were in uncharted territory when work started on breaking out the west wall of the room so that the what was behind it could be assessed. At this point no-one knew what to expect – would there be earth fill, or a void under the Steps? The ensuing discoveries could have come straight out of a ‘what happened next’ feature. The removal of a few facing stones immediately showed that we had a problem – a substantial one. Some earth fill was exposed, but so were several stones – mainly tufa blocks – set horizontally. These had all the appearances of quoins or jamb stones. They lay directly behind a late 12th -century wall-face, and thus (as far as we could see) had to pre-date it. No previous architectural or historical study of the Cathedral had ever suggested that any earlier structures had existed on the site of or beneath the South Quire Aisle. Clearly a major problem had been uncovered, but the very small initial exposure (Plate 30) was insufficient to define exactly what had been found and how this would impact on the proposed lift. There was little option but to widen the hole in the wall, and also excavated down from the Kent Steps as planned – in essence, to dig most of the lift shaft. This was carried out during the second half of September 2014: by the beginning of October it was clear that the issue was severe enough to threaten the very existence of the new lift. Detailed discussions took place with CFCE, Historic England (in an advisory role), experts in the architecture and archaeology of the Saxo-Norman period in general and Rochester in particular, and within the design team. The nature of the discoveries eventually precluded any possible redesign of the lift in the same location, leaving a stark choice – continue with, or abandon, the access lift. After extended discussions, on 5 January 2015 CFCE stated that they were “convinced that these discoveries could not have been anticipated or mitigated against in advance”, but confirmed that “the Commission [was] unanimous in being of the opinion that destruction of the Norman discoveries would be unacceptable under the Care of Cathedrals Measure”. Condition 7 of their permission was invoked, and the access lift had to be abandoned because of the nationally significant remains that had been found.

Plate 30: The gradually expanding hole in the west wall of the side crypt on 19 September 2014, a few days after the masonry had first been exposed. It was becoming clear that one side (the jambs) and a threshold step of a doorway had been found, but this had to pre-date the 1179 fire which had caused the rebuilding of the eastern arm and crypt of the Cathedral.

The opening up had revealed an earlier wall (202) behind the western face (201) of the side crypt (Figure 50). This wall was made entirely from tufa ashlar blocks and appeared to run northwards – presumably to join up with the known south wall of the Norman eastern arm (the GPR survey had shown that this survived beneath the floor of the South Quire Aisle – Plate 5). It also turned to the west, however, and extended back for at least 1.5m in that direction. This face retained an intact rendered surface across the whole of the exposed area; no trace of paint or other decoration was evident on the render’s surface. The ‘front’ of the wall’s alignment, meanwhile, continued south beyond the return/jamb as a stone threshold or step (203) running towards the outer wall of the South Quire Aisle (which, according to all previous understanding of the Cathedral’s history, was part of the rebuilding after the fire of 1179). The continuing excavation then exposed a second step (206) 0.5m back (west) from 203, with a rise of 150mm. The ‘ghosts’ of a further two steps (219 and 220; Plate 31) were visible as scars/holes at the base of the westward return of wall 202. These defined steps 0.45m and 0.34m deep, each with a rise of 190mm. How many more steps existed to the west is unknown; neither can we be certain of what floor level the steps were rising towards, although it is likely to have been one at a lower level than exists now in the South Quire Aisle. Presumably the target floor level would have been one of the lower ones seen by Irvine in his 1874 tunnel (and partly reexposed in 2016 – above). The threshold itself was c 0.7m above the floor level of the side crypt, but is impossible to know whether there had been any further steps to the east because the side crypt itself would have destroyed them. That said, there was no evident sign of a scar from any removed steps in the limited exposure of wall 202 beneath the threshold. Allowing for a step down from the latter of c 150mm, it is suggested that he contemporary ground level would have been about 0.55m above that of the side crypt. This is substantially higher than the known floor level in the Norman bays of the crypt, but below the expected medieval floor level in the cloister walks (which are known with some certainty due to contemporary openings/thresholds in the Chapter House and dorter in its east range).

Plate 31: The north jamb (with its tufa blocks), threshold and step exposed behind the west wall of the store. The ‘ghosts’ of two further steps are visible in the right-hand photograph. Scale 1m in 0.5m sections.

The excavations also exposed a second jamb (214) on the south side of the threshold. This jamb comprised a short ‘stub’ of masonry against the lower part of the south wall (215) of the South Quire Aisle, extending for 0.32m north of it; the stub would have been c 0.44m long (ie to the threshold line). The two visible sides (north and west) of the jamb were again rendered, but the masonry was visible in several places and was all tufa. On the west face of the jamb the render (216) continued round onto wall 215. Jamb 214 survived to a height of 1.85m above the threshold; the springing and arch do not survive, but may not have been much higher than this. The scars of an upper and middle iron pintle survived in the north face of the jamb, showing that a door had hung here and again suggesting that threshold 203 was indeed at or very close to the bottom of the flight of stairs.

Plate 32: View of the Norman remains in the lift pit excavation, with jamb 214 butting against wall 215. The window jamb to the west of 214 is clearly visible, with infill 213 blocking it. Note the outline of the removed treads of the Kent Steps at top right as well.

The upper courses of jamb 214 were visible above the surviving render. Remarkably, they clearly butted against wall 215 (ie the lower part of the South Quire Aisle wall, and thus in stratigraphic terms post-dated it (though this need not represent a long gap in real time). The use of tufa, however, seems to place wall 202 and jamb 214 firmly within the Norman period – this stone was much used in the Norman cathedral, but the supply had been exhausted by 1150. The lower part of the South Quire Aisle wall (215) therefore must be of Norman date as well, rather than late 12th -century as previously understood. Furthermore quoin stones of an opening were clearly visible in wall 215 only 0.3m west of jamb 214. These did not extend down to the level of step 206, so it seems likely that the jambs formed the east side of a window rather than a door. Blocking masonry (211, with surface render 213) to the west of the jamb was presumably put in place when the South Quire Aisle took on its current form in and after the late 12th -century rebuilding.

A further point needs to be made. The two jambs did not seem to be set at a precise right-angle to the southern wall. They were angled very slightly backward from 90 degrees. This does not simply represent a splayed opening: the west wise of the south jamb is definitely not at 90 degrees to the south wall. It was also apparent that the north jamb/wall was splayed outward from the vertical: this may have been a consequence of damage during the late 12th -century construction works, but it seems more likely to have occurred in one of the fires that affected the Cathedral before those works took place.

Plate 33: Left – the door jambs seen from behind, ie the west, with the wall of the South Quire Aisle to the right. Scale 2m, in 0.5m sections. Right – the jambs of what must be a window – it does not continue to floor level – with later (presumably late 12th/early 13th -century) rendered blocking to the right. Note the high quality and crisp condition of the tooling on the jamb stones.

The Norman remains were left in situ after the lift had to be abandoned. They remain on view in a small window built into the re-faced west wall of the side crypt. The Kent Steps were rebuilt, and a new stair lift was installed to replace the old one (which was no longer fit for purpose and, of course, had been removed in 2014). A second access lift in the vestry under the Chapter Library had always been planned. This was installed as planned, and thus inclusive access was achieved – albeit only from the cloister to the crypt. A longer-term solution remains to be designed.

Some final comments in regard the early Norman crypt

One of the most obvious comments in regard all of the above is that there was not a single sherd of pottery that was of any assistance in dating any part of the structural remains. That story was repeated in all the areas examined. The skeletal remains found in the eastern annex, if examined, may however enable us to understand the purpose of that room.

To the south, it has long been known that the south aisle has a complex structural history and the finding of the stair has made it even more complicated. That tufa ashlar masonry was being used on this scale precludes the passage being constructed after c.1140 and a date nearer 1100 to 1120 would be much more acceptable. If that last point can be agreed a sequence along the following lines may have taken place.

a. The Norman crypt was built and completed in the 1080s.

b. A decision was made to add a room (previously unknown) to the south. Thisroom (perhaps a vestry) was completed. Two round-headed arches/recesses in the South Quire Aisle wall on the south side of the Kent Steps may relate to this room (Figure 25).

c. A stair was designed as part of the ‘vestry’, presumably from the outset, but the south jamb of its door was not bonded into the south wall. The vestry was connected to the new south aisle, the wall of which butted up to the north-east corner of a building (the cloister west range?) that was already in existence. Another window was inserted or designed from the outset to give light to the narrow passage-way (Plates 32-3).

d. This arrangement lasted until the late 12th or, more likely, early 13th century when the South Choir Aisle was altered. The passageway was blocked and infilled, and the south wall was largely rebuilt with new lancet windows and a tomb recess. Externally, if examined carefully, the remains of the old wall can be seen at its base.

e. The arrangements in the South Quire Aisle were altered at least twice more during the course of the 13th century. Figure 28 attempts to give some idea of what may have happened.

Discussion

When we come to the development of the Norman church and monastery it would be good to be able to say our documentary evidence allows us to build up a picture of building and alteration through the course of the late 11th and 12th century. Unfortunately the documents have to be considered suspect throughout the whole of this period and beyond. From the 13th century the Rochester monks were professional forgers and before that our sources include hagiographies, which are always unreliable, and a few other meagre statements. This position was not helped by the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth century historians (and into the 20th century by archaeologists) who created all sorts of problems in relation to the translation of medieval documents, faulty editing and failures to understand what they were looking at (admittedly, at least, from a document point of view, nearly all archaeologists suffer from the latter problem). Rather than just making statements or giving opinions in regard the (pretty meagre) documents relating to Gundulf or Ernulf, we have, I think, to look at several factors. What was a bishop meant to do, the time scales involved, the fires (known from good sources) of 1137 and 1179. and above all the architectural evidence. Of the latter the present writer freely admits he knows next to nothing and has to rely entirely on the works of others (e.g. Hope, Flight. McAleer, Tatton-Brown). By looking at the architectural detail, the archaeological stratigraphy, the reliable historical 'facts', perhaps along with what medieval writers' left out we can, I think, put forward a coherent development. With the exception of the archaeology all of this work has been undertaken by others and basically the only thing AW has done here is to bring it into a simpler form. 1. Gundulf starts building a church either in the late 1070s or, more likely, very early 1080s (c.1082). This start date is based upon: a. His bringing twenty-two monks to Rochester c.1082 to replace the five Anglo-Saxon canons. It would be expected that a monastery in the continental form would be created b. The standing west front of c.1155-1160 has an earlier west front fossilised within (Livett 1889, 282, 274-5). The chances are that the earlier structure will not date to after the fire of 1137, therefore the embedded material must be earlier than that fire. As there is no sign of a still earlier west front it would be pure fantasy to believe that the end of the cathedral was left open for several decades, therefore a date in the late 1080s or 1090s for its completion seems a perfectly reasonable deduction. This earlier west front had plaster down to the base of its internal wall (ibid. page 275) which tells us that the wall was completed. Other than any wall paintings the plaster would be the last part of the structure to be put in place and would only be put in place once the roof was on. 2. The east end, or at least the crypt, was completed c.1088 (Plant 2006, 39; McAleer 1999, 45) when the body of St. Paulinus was transferred to the new building. The whole church was probably completed by c.1100. Three areas have been suggested as the new burial place of the saint. On the right (south) side and just in front of the high altar of the early Gothic and later church (Flight 1997, 67 and page 196, Fig. 24) and, for the early Norman church, the eastern annex at presbytery level (Hope 1898, 209 and Plate I), or the eastern annex within the crypt (Palmer 1897, 7; Arnold 1989, 16- 21). The finding by Hope of a wooden casket containing skeletal remains in the eastern annex of the crypt must surely make this the favoured position. If such an idea is accepted one can't help but think that there was a chapel dedicated to the saint above the crypt chamber. To this point we shall return, but suffice it to say that the skeletal remains and the timber fragments, uncovered again in 2015 even though much disturbed, are worthy of radio-carbon dating. If those dates come out as seventh century then tooth isotope analysis might show whether the individual was born to the south of the Alps. 3. According to his hagiographer Gundulf built a monastic complex for the monks, 'as well as the site allowed'. The latter point at least shows that the writer had some knowledge of the topographical problems confronting the bishop. 4. There is no evidence that Gundulf's immediate successors, Radulf or Ernulf, rebuilt the east end or nave. Admittedly for the east end the late twelfth / early thirteenth century rebuilding would have destroyed any architectural evidence and also, admittedly, there is no documentary evidence for that rebuilding. However, one would expect some sign of such a structure and its destruction within the archaeological remains. There is, when looked at objectively, none. Such archaeological evidence that is used is ambiguous and some can be shown to be wrong. 5. Ernulf rebuilt the Chapter House, dormitory and refectory. How much of those buildings still exists is a debatable point. 6. The nave was rebuilt in the 1140s, possibly, indeed probably, due to the fire of 1137. 7. The east end was rebuilt c.1180 to c.1190 after the fire of 1179. 8. The rebuilding of the quire, crossing and transepts followed during the early and into the mid decades of the thirteenth century. All were probably completed by c.1240. 9. The upper part of the crossing tower was constructed by Hamo de Hethe in 1343. 10. The Lady Chapel was built c.1500.

Gundulf's crypt