Archaeology of the Priory Cloisters

/Archaeologist Alan Ward discusses the archaeology of the Cathedral Priory of St Andrew within the Precinct at Rochester. Featured in The Hidden Treasures, Fresh Expressions Project Archaeology Report, Keevill Heritage 2021.

References in the c. 1225 Custumale Roffense paint a picture of the Cloisters as a place also occassionally accessed by lay servants, and was also a place through which processions passed. The requirements of the Church Attendants stipulates:

‘…In winter before the striking [of the bells] for assembly, they will place a light at the 4 corners of the cloister, for when it is the procession from the chapter into the refectory; and after compline they extinguish it…After the octave of Pentecost, the curtains and skins and cushions are to be shaken out in the sunshine in the cloister, for which they have four pennies for drink…’

A translation of the duties of the church Attendants as recorded in the c. 1235 Custumale Roffense.

Duties of the Church Attendants, c.1235

Recording the responsibilities of the church attendants.

EXPLORE

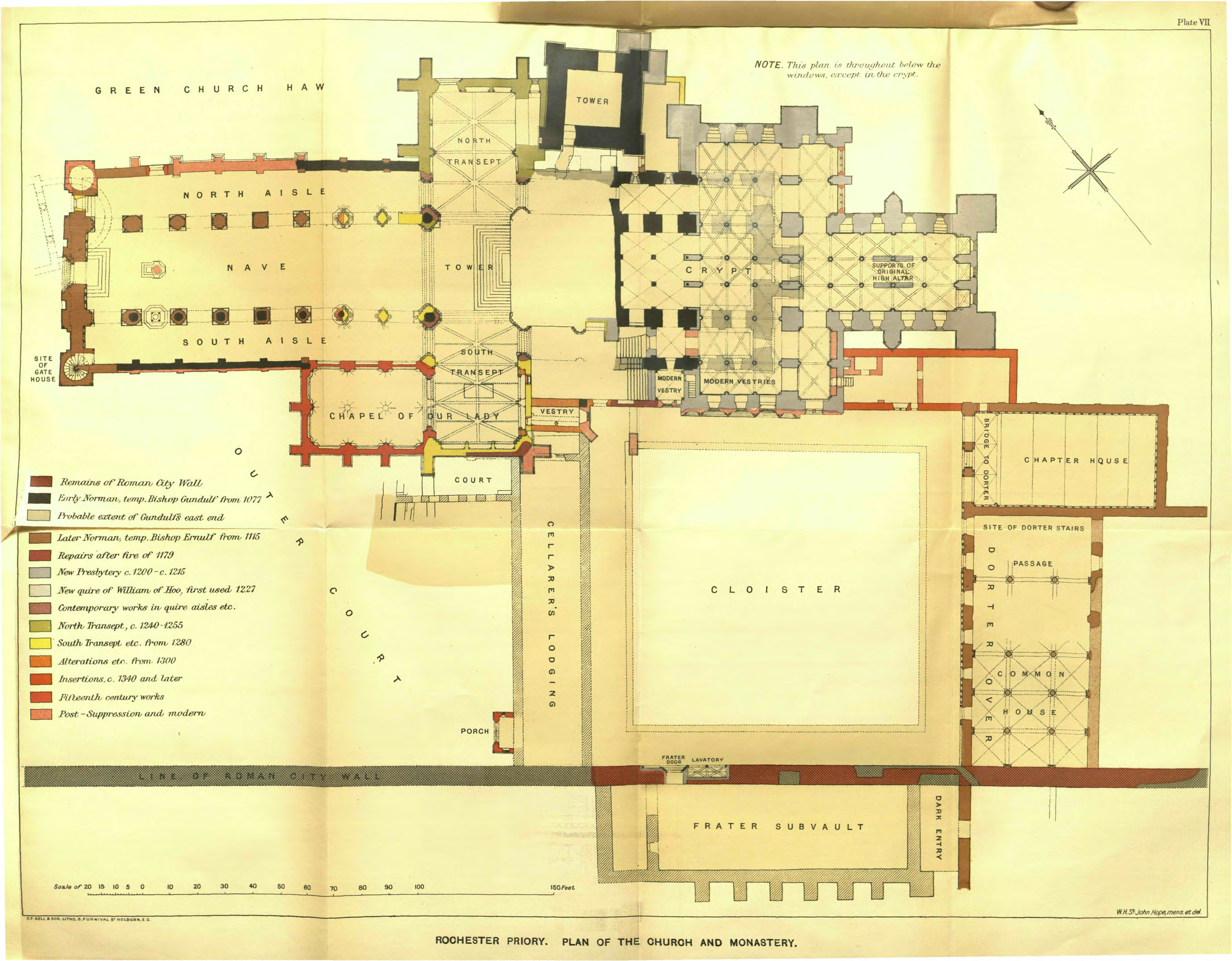

William St John Hope’s plan of the priory buildings around the cloister. Aerial photography conducted in 2017.

2016 Cloister Garth excavations

Excavations in the cloister garth and north walk produced some very unexpected and interesting structural remains (Figure 63). It was also the only area where Anglo-Saxon dark earth was observed over an extensive area. Much of the north cloister walkway was excavated, albeit only to shallow depths towards the west because of the upslope of the new (wider) pathway in this direction. Several trenches were also dug in the central grassed area (the Garth - trenches 1 to 4) for drainage. In the medieval period the Garth, just as now, was kept as a regularly mown grassed area (Hope 1900, 29).

3D model of the Cloister Garth in 2017 from aerial photography by SUMO Survey.

In trench 2 brown loamy clay (1658, the same as 1622 along the north cloister walkway) was observed across the Garth lawn. This was a buried topsoil of unknown date but probably Roman. The geological Brickearth was found beneath was this soil. Anglo-Saxon dark earth was observed at the base of trench 3, and therefore geological natural was not seen: the brown loamy buried topsoil should have been present between the dark earth and Brickearth.

Trench 1: Towards the western side of the central grassed area a 5.25m x 4.25m soakaway trench (Trench 1; Figures 63-4; see Plate 14) was machine excavated to a depth of 2.75m. In the lowest 1m, varied geological deposits (1597) were observed. Brickearth-covered sand and flints were seen on the east side, with sand and flints or sand elsewhere. A disturbed brown topsoil (1596) of Roman or (less likely) Iron Age date overlay these. None of this represented re-deposited geological material used in the late 2 nd -century defensive rampart, because in situ geological deposits (and topsoil) continued more or less at the same level northwards all the way across the crypt. As far as could be judged none of the soil deposits above represented the rampart either. Redeposited Brickearth deposits which were very likely the remains of the rampart had been seen immediately to the west in 2009 in a trench dug along the line of the west cloister walkway (Keevill and Underwood 2010), but here such deposits were completely absent. Assuming that the rampart had once been present here, it had been removed completely. If it was absent, for whatever reason, that may explain why the cloister was constructed in this area rather than further to the west. Only further excavation might establish whether or not there was a gap in the earthwork defences at this point. If one did exist it is unlikely to indicate the presence because a gravel road surface should have been present behind such a feature. No such surface existed. Remains of the rampart are known to exist within the Deanery Garden to the west, and it seems likely that it also exists below the west cloister walkway. On balance, therefore, the area of Trench 1 would appear to have suffered greater truncation. That greater depth of levelling may be connected with the insertion of wall 1590 (see below) and the gravel foundations revealed in Trenches 2 and 3.

It is possible that the fragmented mortar and chalk rubble foundation, 1590, was the wall of a Roman building (see part 4.1 and Plate 14, above). It cut a layer containing many large Roman floor tiles, however, and it is therefore more likely that it was later in date. It may have been the external wall for what is probably the east range of Gundulf’s cloister. Certainly its level of c 8.12m aOD compares well with the c 8.20m aOD for gravel foundations to the north (see below), and is much lower than would be expected if it was a later (ie post-medieval) feature. A fragment of brick (which did not appear to be Roman) found within the infill of the construction trench must be intrusive. The possibility that 1590 belonged to a post-medieval garden design cannot be dismissed entirely, but it seems much more likely that the foundation does represent the east wall of the western walkway for Gundulf’s east range. A flint yard surface (1588) was observed in the north and east sections of the trench above 1590; this surface is assumed to be of post-medieval rather than medieval date. It could date to c 1540 when Henry VIII built a short-lived palace within the medieval buildings of the cloister and infirmary. Alternatively it could be contemporary with the house of the third prebend, constructed in 1805. A brick-built culvert (1583) and a circular soakaway in the south-west corner of Trench 1 can safely be regarded as belonging to that building.

North Cloister walkway trench: As stated above (page 37), along the line of the north cloister walk (Figures 36 and 63c; Plates 62 and 63) and above the Roman top-soil of brown clayey loam (1622) a layer, or more correctly layers (1619 and 1621; Figures 37a to 37c), of dark grey silty loam straight away made an impact upon this writer. This material with many charcoal flecks and some streaks of charcoal has to be the Anglo-Saxon dark earth deposit. Truncation of this dark grey soil, along the line of the north cloister walkway was certainly undertaken on one occasion, probably twice and perhaps on a third occasion in the medieval and early post-medieval periods. The whole length of the north cloister was truncated again in the 1930s and yet again in 2015 for the insertion of a new path.

The length of the north cloister walkway, and the area to the south, would have been levelled when the cloister was first planned. The former would have been levelled again when the final tile floor was laid in the fifteenth or even the sixteenth centuries and yet again when it was dug up c.1560 and, yet again, when a brick path was laid in the 1930s. The 2014-2016 levelling for a new path entailed not only removal of the 1930s bricks but also digging into the adjacent embankment for a width of about 1m.

Along the line of the north cloister walkway trench and some 2.35m away from the south wall of the vestry and southern minor transept a 1.25m wide gravel foundation (Wall 1534) was uncovered (Figures 58, 63, 65, 66, 67a to 67e and 68; Plates 64 to 67). Both the east and west ends of this foundation were seen and gave a length (more correctly width) of 9m for this building. Its north to south length is not (yet) known. The fact that at both ends an internal corner was observed showed that this gravel had to represent a structure and not just a boundary wall. On this foundation the lowest course of masonry (Wall 1533) measuring c.1.60m east to west and 1m north to south (Figures 65b and 65c and, 66). At both east and west ends of the gravel, other foundations could be seen. At the west end cutting into the gravel a small area, just 1m long and 0.30m wide, of black flints (Wall 1549) was identified (Plates 64 and 65). This material had been largely destroyed by a large early nineteenth century pit for the disposal of rubble (see below). At the east end, fragments of a very distinctive coarse yellow shelly mortar (Wall 1547) survived in some quantity (Figures 65c, 67a, 67g and 68; Plates 66 and 67). There was enough to show that this was not just residual dumped material, it could be seen for a length of 3m and represented a wall at least 1m wide. Up against the east side of the gravel foundation a substantial lump of this material could be seen within its own construction trench (Cut 1548). When cut, this construction trench had left a soil wedge between it and the gravel foundation showing that the latter must be the earlier in date.

From these three features no artefact dating evidence was recovered. The shelly mortar is however a very distinctive Norman material with an expected date of c 1100-40. This material has appeared in at least two other buildings in Rochester, both of which have to be Norman in date (see below, pages 72 and 73). Logic also tells us that the gravel foundation has to be one of two dates. It is either of the time of Gundulf c.1085, forming his cloister or infirmary range, or that of Ernulf c.1120, forming his cloister range. This will be discussed further below. We will return, also, to the further gravel foundations observed in Trench 2 and Trench 3 immediately to the south of the cloister walkway area.

Any floor deposits along the walkway, whatever the material used, were completely removed when the late medieval tile floor was inserted. In turn when that was dug up, presumably in the midsixteenth century, both the tiles and their mortar bedding were removed. There was a very large amount of broken floor tile, much of it glazed, in various soil deposits (1627, 1532 and 1514; Figures 67a to 67h) and it seems reasonable to assume these represent the last floor of the medieval walkway. Based on the tile fragments a late medieval date can be suggested for this floor. The soils levels 1514 and 1532 both produced pottery of the seventeenth and eighteenth, and indeed in the latter instance, of the nineteenth centuries. We should remember, however, that these soils were used as a garden for over three hundred years and would have seen much disturbance. The sixteenth and earlier seventeenth century pottery found within their matrix almost certainly gives a more accurate picture of when they were first created.

Within the cloister walkway itself, but above the tile debris, traces of mortar construction deposits (1603 and 1629) remained in place. The latter consisted mainly of a grey mortar with a considerable amount of burnt chalk and charcoal flecks within its matrix (so called 'salt and pepper mortar') datable to the eighteenth century or, perhaps, the very early nineteenth century. This material probably represents the repair or insertion of a door and window into the central part of the south wall of the vestry. A further window was at one time situated at the east end of that wall, for traces of a straight joint in the external face of the wall could be seen and a fragment of 'salt and pepper mortar', showing the area had been infilled, was observed when a new door was inserted at this point.

Immediately to the south of Wall 1534, the wide and early gravel foundation, there was a narrower foundation (Wall 1538 / Wall 1663), 0.50m wide, consisting of chalk rubble bonded by a pale yellow mortar (Figures 65b and 68; Plates 65 to 66 and 72). Where the whole width of the wall was seen in a single section at its east end (here numbered as Wall 1524), it was found to measure 0.85m wide. This foundation represented the outer wall of the north and east cloister alley or, more correctly, the outer wall in its finally form. There was almost certainly an earlier garth wall at least on the east (Wall 1683; Figures 68 and 69d), presumably dating to c.1160, In its final form, on the east, a cloister alley nearly 4m wide was created. The upper portion of this later garth wall had been robbed by Cut 1538 and this robber trench was infilled with brown soil, fragmented mortar and broken floor tiles (1539). Above this was a 0.40m thick deposit of soil (1532 and 1514) also containing floor tiles. A considerable quantity of peg-tile along with a Caen Stone block was observed within context 1527, possibly pit fill although no cut was seen. Presumably the peg-tile came from the roof of the cloister walkway. These soil deposits and the cloister wall had been cut away at their west end by the early nineteenth century rubble filled feature (Cut 1505; see below). No artefact evidence was recovered which allowed the construction of the garth wall to be dated, but it is presumably contemporary with the building of the library in the late fourteenth century. Crushed Caen Stone rubble (1551) on a clay bed may have been a foundation coming off at a right angle from this garth wall into the north cloister walkway (Figures 65b, 67a and 67g).

Another east to west aligned foundation (Wall 1512; Plates 68 and 69) situated at a higher level, just 0.25m below the surface of the top-soil, had also been cut away at its west end by Cut 1505. This postmedieval foundation (Figures 65a, 67c to 67h; Plates 62 and 63) followed the line of the medieval cloister wall, but was separated from it by the soil deposits. The foundations consisted of all sorts of material, chalk and stone rubble, with brick and tile fragments and, luckily, a few fragments of pottery and clay pipe, including two bowls one of which was of very early date. Overall this material can be dated to the seventeenth or earlier eighteenth centuries. The wall represented by this foundation is probably shown on a plan of 1772 (Fig. 28b), but had disappeared by 1801 (Fig. 28c). That the foundation represents the laying out of the garth as a garden for one of the predecessors of Canon Foot, the prepend at the time the plan was drawn, and separated the garden from the cathedral, seems the most likely interpretation for the presence of this feature.

All of these deposits were cut by a very large pit (Cut 1505) some 16m long and of unknown width and depth (Fig. 70). This feature contained masses of stone, mainly Reigate Stone in the form of rubble, ashlar blocks and architectural fragments with some Caen Stone and amazingly some large fragments of Onyx Marble (Plates 70 to 72). The latter was only used in the later Norman period (c.1160) at Rochester Cathedral, notably in the pillars of the East Range blind arcade and west front. This material was only used at a small number of other prestigious buildings; Canterbury Cathedral, St. Augustine's Abbey, Canterbury, Lewes Priory and the mid-twelfth century bishop's residence at Wolvesey Palace, Winchester (Tatton-Brown 2014) . It originates as a calcium carbonate deposit from only one known site, the Eifel Roman aqueduct to the south-west of Cologne where the sediments had solidified into stone (ibid.). Not only were shaft fragments of this material found, but also a shaft base forming the largest fragment of Onyx Marble seen by this writer. However, most of the infill consisted of chalk and mortar rubble long with some brick fragments. This feature had been dug as a pit to get rid of the stonework of the medieval face of the south minor transept when that was eventually replaced in 1825-1829 by L.N. Cottingham. The easiest way to get rid of rubble is to bury it. The soil dug out would then just be spread and this probably forms the upper c.0.30m or so of soil within the cloister garth. Up against the wall refaced by Cottingham, two brick buttresses had been constructed c.1752 to prevent the south wall of the minor transept from collapsing (Figures 62 and 70; Plate 73). One had to be repaired just seven years later (Holbrook 1996, 192). In the period 1826 to 1829 the stone facing, most of which had been Reigate Stone was replaced by one of Bath Stone which is that we see today. The brick path, recently removed, was laid down in 1935. This has now been dug up and replaced by another path sloped so as to aid wheelchair access.

We return to the lawned area of the garth. Excavation of two trenches (Trench 2 and Trench 3) to the south of the north cloister walkway produced the most surprising and interesting archaeological remains in this area.

Trench 2: Trench 2 was dug for a new drain pipe, it was just 0.50m wide, but 1.80m deep (Figures 68 and 69a). It stretched for 8m from the north cloister walkway trench to a large early nineteenth brick soakaway. At base there was brown clayey loam (1658) which is regarded as the Roman top-soil. There was no sign of the distinctive dark earth deposit which had appeared just 2m to the north, but this may have been due to seeing the soil deposits in this narrow and deep trench rather than in plan. Be that as it may, the soils at base were again cut into by orange brown gravel foundations.

Wall 1659 was parallel to and just 1.70m to the south of Wall 1533 / Wall 1534. A mortar deposit (1657) rose up and passed over the south side of this gravel foundation for 0.15m. Whilst stratigraphically later than the gravel the two deposits are considered to be contemporary. The actual upstanding wall could easily have been narrower than the foundation material, the latter widening out on one or both sides of the wall and forming an offset.

This narrow passage may have been a slype (Keevill pers. com.). With Wall 1547 on the north and the polygonal apse (see below) on the south such blocking those two directions, the passage may have given access to the infirmary ranges.

Some 2.85m further south, but only in the east side of the trench a further gravel foundation (Wall 1666) was observed. At a slightly higher level than the top of these two foundations a 0.10m - 0.20m thick deposit of a very light brown mortar (1657) was observed. This material was relatively compact and appeared to form a floor surface between the walls of this large building (Figures 68 and 69a). That it survived and the masonry of the building did not is easy to explain, for when the latter was 'robbed' the floor, as well as, perhaps more surprisingly, the gravel of the foundations, was of no use to the demolition gang and was left in situ and reburied. This mortar passed to the west of the southernmost area of gravel foundation (wall 1666) observed. The presence of the mortar showed there was a definite gap between the west end of that foundation and any continuation that may have existed further to the west. Whether there was a door from one room into another at this point or this small southern area of gravel represents the base for a pier or shaft can only be found out by further excavation.

Trench 3: In addition to these discoveries, in a trench (Trench 3) adjacent to the east walkway of the cloister, further gravel foundations were uncovered (Figures 68 and 69b to 69d; Plates 74 to 77). At first the foundation (wall 1676) could be seen in section to be on the same line as wall 1659 and continuing that line for c.0.80m to the east of Wall 1536. Then, however, in plan both externally and internally this material turned southwards, not at a right angle, but at about forty-five degrees. A length of c.0.70m was exposed with slight traces of the lowest course of masonry, or at least demolition material, surviving on its western side. We have here the start of what can only be described as a polygonal apse. The foundation exposed passed below the brick walkway of the east cloister so we do not know how far eastwards it extends. That it must turn to the south and then back to the west is certain. Presumably it forms half a hexagon, but depending on that eastward extent and its total width it could be half an octagon. Trial trenches at strategic points in the Chapter House and along the inside of the east cloister walk perimeter wall would almost certainly tell us.

Short lengths of Wall 1674, the later medieval cloister wall outer wall, were observed on the west side of this trench and a small fragment of an earlier wall (Wall 1675) was seen on the east, immediately below the modern Ragstone wall (Fig. 69d; Plate 76). Wall 1675 is assumed to represent an earlier garth wall presumably constructed when the standing East Range was built either in c.1120 or c.1160 and creating a cloister alley just 2.50m wide. What may have been the remains of yet another garth wall were represented by mortar rubble containing a peg-tile fragment (?Wall 1683) and a definite cut (Cut 1682) containing a mortar and soil mix (1681). More likely, however 1683 is part of the robber material and the feature as a whole represents the robbing of Wall 1675.

Trench 4: A further trench was dug in the north-west corner of the lawned area for an access slope, but nothing or archaeological significance was seen in the 0.50m (maximum) depth of soil that was removed (Fig. 63).

The east range and Chapter House: A single trench, 0.60m wide and 0.80m deep, for a new water pipe was excavated by the groundworks team west to east up against the north wall of the Chapter House with a shorter trench aligned north to south across part of its width adjacent to the west front of the St. Andrew's Centre (Figures 71 and 72).

The ground surface inside the Chapter House is at two levels. A lower level to the west, which is the result of clearing the door and cloister alley in 1935 when parts of the medieval tile floor were seen and a higher level over most of the interior. Previously, in 1766 a skeleton was found when a new cellar for the deanery was dug and was supposedly fully seven feet in length. A stone coffin was also found in 1770 but the skeletal remains had been reduced to dust (Denne 1817, 86 note). The note implies that the skeletal remains were those of Paulinus. AW will say here and now, they were not and neither was the skeleton 7ft in length.

Areas of demolition material (1691) were seen and, in the soil (1695), below a considerable amount of broken floor tile and a few sherds of post-medieval pottery. The only feature of note was a 0.30m wide north to south aligned wall (Wall 1692) made from chalk and Reigate Stone rubble. In the south face of the trench, whilst the full depth of the wall (1693) may not have been exposed a compacted area of fl mortar may have been the level of a tile floor. This wall abutted the 0.50m wide stone work (1697), which is regarded as part of the bench that would be originally have been situated around the Chapter House for the monks to sit on during meetings. Only a 1.80m length survived. Most of this bench had probably been destroyed c.1540. An offset foundation for the wall itself, upon which the bench sat, existed at a lower level. Presumably it was at this junction between foundation and bench that the medieval tile floor would have been set.

Wall 1692 was situated just 0.60m to the east of the late fourteenth century inserted door giving access to the vestry, the wall and door effectively making the Chapter House some 3.50m shorter. In the south wall of the Chapter House the scar of a dividing wall can also be seen, but does not quite line up with that uncovered in the trench excavated. Presumably there is a dog-leg, perhaps at the position of a central door within the length of this inserted partition wall.

In the north wall at a higher level the blind arcade that went around the Chapter House can, in places, still be seen (Fig. 72a; Plates 78 and 79). All of its facing stone has been lost, but several of the bases for the shafts, which supported the arches survive on a 0.15m wide offset situated 1.25m above the present ground surface. Some of the shaft bases can also still be seen in the south wall, but only traces of the blind arcade could be identified. In one of the upper rooms of the St. Andrew's Centre part of the arcading with its facing stones still intact survives. Above the arcade inserted much weathered corbels, originally depicting carved angels and supporting a new roof, possibly of the fourteenth century (Tatton-Brown 1994, 21) or the second half of the fifteenth century (McNeil 2006, 202 note 9), are still in place. Presumably they replaced the twelfth century earlier corbels within the same sockets. Cutting into the arcade arches were seven large joist holes. These holes were mirrored in the south wall. This must mean that a timber floor was at one time inserted into the Chapter House. However, the joist holes do not continue into the westernmost 4m part of the structure. The floor may not have been completed or the western end acted as an open gallery or a timber partition end wall existed at this point.

Also in the south wall, the threshold of an inserted and now blocked door at first floor level, originally giving access from the dorter to the library, the latter situated above the vestry, can still be seen. Access from the dormitory to this door was across the dorter stair by means of a three arch bridge inserted across that space and dated to 1342 (McNeil 2006, 185, 202 note 9). The tree ring date of c.1360 from the roof timbers of the library would suggest the bridge would be slightly later. With the identification of joist holes it might be assumed that a timber floor was also inserted at this time and connected with the bridge. However, no joists holes could be seen in the western 6.50m of the building, which is saying there was a 5m gap between floor and bridge and a 4m gap between floor and partition wall to the east of the inserted doors t ground and first floor level in the Chapter House north wall. Also of course one would expect the new roof to be visible at Chapter House meetings. It seems far more reasonable to assume that the date for the insertion of such a floor would be at the time Henry VIII's palace was being constructed c.1540. One suspects that it was never completed.

Although not part of the crypt / cloister project, mention should be made here of observations that took place within the area of the dorter undercroft in July 2016 (Fig. 73; Ward 2016). Here the project entailed the observation of the machine excavation of a trench c.40m long by c.0.40m wide and c.0.50m deep. For most of its length only disturbed soil and rubble infilling service trenches was encountered. However, in the very last 0.50m of the trenching, at its far north end, a medieval respond, was observed in the side of the trench. This respond was one of those visible when Hope undertook his excavations in 1884. The abacus, the rectangular stone block above the capital and the capital itself, had long since been cut back, but the shaft was undamaged. Two other dormitory undercroft shafts with their capitals are also visible within the yard area and from these Hope was able to work out the number of shafts and bays within the undercroft.

-> Plan and elevation drawings of one of the recessed piers in the eastern face of the surviving Dormitory facade, now below the level of the pavement. Hope 1900, figure 43.

Hope also tells us that the remains of the east door of the passage through the undercroft were visible in his day. This is now used as a window. With the realisation that the apex of this door still existed it must follow that part of the east wall of the dorter range also survived. A ledge above the door almost certainly indicates the level of the dormitory floor. The south end of this length of wall has a quoin belonging to the seventeenth century deanery and a distinct crack between it and the wall can be seen. No certain break could be seen within the height of the wall above the ledge. The present writer would not be so foolish as to say the full height of this wall is medieval in date and certainly refacing, with flint galleting, normally regarded as being of sixteenth century date at the earliest, possibly indicates rebuilding. We can, however, say that a substantial block of this masonry is medieval, presumably twelfth century, in date.

We can perhaps go a bit further. The King's School building at the north end of the yard is just c.4.50m wide and has been built over the site of the dorter stair rising from the east walkway of the cloister up to the dormitory level. Except for its ornate decorated door in the west front of the dorter wall the stair has long since been destroyed, but it is very noticeable that at first floor level at the east end of this eighteenth century King's School building large stone blocks one on another form what appear to be the western jamb of a door. These blocks survive for about 1m in height. Above are mouldings inserted at a later, probably relatively recent (?nineteenth century?), date. However, the present writer suspects these large blocks of Reigate Stone and Ragstone represent one side of the twelfth century doorway into the dormitory.

The north wall of a structure on the south side of the yard was also of some interest for it varied in style, parts vertical and parts sloping, the Ragstone courses of which didn't match up. The sloping portion of the wall, behind (?)nineteenth century refacing, is almost certainly the core of the Roman town wall.

We will return to the date of the Chapter House and the East Range as a whole in the discussion section below.

The west and south cloister alleys: Observations in other areas of the cloister were pretty minimal. At the south-west corner part of the wall of the house belonging to the third prebend was observed, but 0.90m to the north, an earlier wall built at an angle to the west cloister walkway was also present (Figure 63). This wall (Wall 1816), bonded by a distinctive very light brown mortar, which the present writer nearly always regards as being of medieval date, ended in Ragstone Stone blocks which were initially regarded as representing the jamb for a door. This is now considered to be incorrect if for no other reason than that the area later exposed along the cloister alley would have been wide enough to uncover the western side of such a door. Also, no wall was revealed at this point in a service trench excavated in 2009 (Keevill and Underwood 2010, their Fig. 5). The masonry may be a buttress at the end of a wall. That trench revealed the latest floor of the west cloister walkway made from glazed tiles, which now has a 0.30m wide trench cutting through it for almost its whole length. Part of this same floor was revealed in 1982 to the south of the south porch (Bacchus 1985). Details of both excavations have been added to Figure 63.

Although only a 0.40m length of Wall 1816 was seen it was definitely angled at about forty-five degrees to the cloister alley, at about the same angle as the later prebendal house wall (Wall 1811). However, as the two are only 0.90m apart they are regarded as being too close together to form part of the same structural phase. Wall 1816 is regarded as representing an earlier building. Either or both walls could have joined with Wall 727 (2009) and Wall 718 (2009) found in the 2009 watching brief when a new water pipe was laid. These two walls crossed the southern cloister alley and make a right angle with Wall 707/(2009) and Wall 737/(2009). At the time of that earlier project these two walls were described as walls of Ragstone bonded by a lime mortar and probably of medieval date but perhaps reused in the prebendal house. Wall 727/(2009) may have been a boundary wall and Wall 718/(2009) the west wall of a porch for the house, as shown on Hope's 1:500 plan of the precinct (Fig. 6). If any of these walls are of medieval date and as they do not match with the alignment of the cloister, this would suggest they are very late medieval and form part of the palace being constructed in the early 1540s.

In 2015 and 2016 observations were made along the south cloister alley and some detail of walling along with the remains of one capital and one shaft of the cloister alley which, as far as this writer is aware have not previously been noted (Plate 48). The Onyx Marble shaft is very well preserved.

At the north end of the west range the modern brick path was taken and the east wall of the range was revealed for a length of 4m. The most interesting excavation associated with the west range was however, undertaken in 1937 when the southern room of the range itself and the whole length of the cloister alley was uncovered. This excavation, and that of 1982 in the area of the south porch, are mentioned below.

Discussion

Location: Unlike most monastic establishments where the cloister ranges are to the south of the nave the cloister at Rochester is situated to the south of the presbytery and quire. Since the time of Hope (if not before) many, but not all (notably McAleer 1994), archaeologists have believed the original (Gundulf's) cloister here at Rochester was in the usual position, south of the nave and then moved eastwards c.1120 in the time of Ernulf. However, the present archaeological excavations have discovered a range of buildings below the existing garth lawn and for the reasons stated above, in relation to the area of the Bishop's Palace, and here in these paragraphs these remains are regarded as those of Gundulf's cloister.

Documentary evidence: Our documentary sources are again pretty meagre. We have the statement from the Textus Roffensis that (implies) Gundulf built a cloister, ‘also constructed all the necessary offices for monks as far as the capacity of the site would allow', (Hope 1900, 3).

This statement can of course mean whatever the reader wants it to mean. The cloister could be to the south of the cathedral nave, as it should be or to the south of the quire. Archeologically we can now see that the latter has to be correct. As with so much at Rochester what should happen in regard an early Norman cathedral plan does not necessarily actually happen.

Thomas of Nashenden after a fire, but unfortunately we don't know which one, 'gave all the stuff wherewith the Chapter House was covered', (Hope 1900, 10). As with so many of the documents in relation to the cathedral the meaning is ambiguous. Does this mean the Chapter House was refaced with the Caen Stone ashlar or was the 'stuff' merely sacking to provide covering for the scorched stonework so as to prevent rain or frost damage.

Bishop Gilbert de Glanville provided the fund for 'our cloister to be finished in stone', but we don't know what this work actually consisted of. Tim Tatton-Brown suggested it was a stone arcade upon the cloister garth wall (1988, 7), Colin Flight suggested the vaulting of the cloister alleys (1997, 224) may have been his work. However, it may be that his input was considerably more extensive. It is here suggested that the upper part of the east wall with the lower level of corbels which have definitely inserted into the Caen Stone masonry, along with a new cloister alley roof covering, was Gilbert's contribution to the cloister.

Helias (Prior 1214-18) built the doorway for the lavatorium in the South Range and had that part of the cloister towards the dorter covered in lead and the part towards the frater covered in shingles. In 1384-85 one side of the cloister, but we don't know which, was still covered in shingles (Hope 1900, 30).

3D model of the Refectory Dooryway dating to the thirteenth century.

In 1336 Hamo de Hethe (Bishop 1319-1352) began the rebuilding of the refectory, This, new refectory had six large buttresses and an even larger south-east corner buttress along its south wall. One suspects that Ernulf's c.1120 refectory had shown signs of cracking due to having been built close to the north edge of the Deanery Garden Ditch, or perhaps even on recent infill (Fig. 74). If it was being infilled at a date as early as c.1120 then it cannot be the defensive ditch dug in 1225.

Elevation and plan drawings of the Refectory facade and lavatorium, Hope 1900, plate VI.

We know from documentary sources that Henry VIII (surely one of the most obnoxious individuals who has ever been crowned King of England) after he had dissolved St. Andrew's Priory in 1540 took over the ranges around the cloister and the infirmary area as one of the royal palaces between London and the coast. The palace was short lived, being leased in 1543 by Henry and then given outright, in 1548, by Edward VI to George Brooke, Lord Cobham. He in turn sold the cloister ranges back to the cathedral authorities in 1558. Extensive demolition of the palace was supposedly undertaken by Lord Cobham in the course of the 1550s and he, supposedly, took the architectural stone and used it at Cobham Hall in the windows. In an unpublished archive report doubts in that regard are put forward, for the very simple reason all the windows are the same. The have the look of a 'job lot' especially made for the hall (Ward 2008a). It is here suggested it was the cathedral authorities after 1558 who were responsible for most of the demolition of the east and south cloister ranges and the infirmary buildings.

The former dormitory became the King's Lodging (Colvin 1982, 234-6). Apparently, a royal lodge, '.... over and beyond the east range...', is stated as being present even prior to the Dissolution of the monastery (Cleggett 1991, 18; no source for this statement is referenced) and was then '...greatly extended ....' (ibid). Certainly after the Dissolution, at the very least, the king's palace encompassed the cloister and infirmary ranges. The East Range had a great or watching chamber, dining chamber, bed chamber and drawing chamber. These are all assumed to have been at first floor level, the former dorter being divided up into smaller rooms. The privy chamber was situated within the cloister garth and connected to the watching chamber by a corridor built over the cloister roof. This last chamber was presumably timber framed and presumably had a cess pit dug into the garth.

The south range, the former refectory, was made into a Great Hall which in 1542, was converted into (or at least called) a Great Chamber. Quite what the difference was is not explained. The palace also had a 'Counsell Chamber' and it has been suggested this was in the former west or cellarer's range. If correct this also would have been at first floor level above the undercroft of that range.

A new two-storey 'pages chamber' was built somewhere within the garth. This was presumably a timber framed structure, perhaps adjacent to the 'Great Kitchen'. There was also a 'halpas' joining the kitchen. The word halpas usually means a dais or raised floor or gallery, but can also mean a vestibule or porch. Either could connect the pages chamber with the kitchen.

The documentary evidence tells us that seventeen buttresses to support a new roof were built when Henry VIII took over the cloister area. A buttress is shown on the 1798 drawing (Fig. 28a) and six buttresses still survive, just 0.50m high, up against the external face of the east wall of the west range. Those buttresses can be seen to abut the wall and some (but not all) have 'Tudor' brick within their, mainly Ragstone, fabric. The buttresses were present when the west range was partially cleared of debris in 1937 to 19395 (Forsyth 1939) and it seems a reasonable deduction that these remnants are in fact the last part of Henry VIII's palace to remain standing. Admittedly they are not shown on William St. John Hope's plan of the cloister area, but the present writer is not convinced that he saw most of the walling of this range which he has drawn on his Plate VII (Hope 1900). When he saw the cloister area, an early nineteenth century house (demolished in 1937) occupied the south-west corner of the garth and would have disguised some of these buttresses and the others may well have been covered by soil or debris at that date.

Two galleries were built. One of these is recorded as being over the new cloister roof.

The 'great halpas' connected to the King's Great Chamber and the other, a 'little gallery', was situated between the old lodgings and the new. Hope tells us a halpas was over the south cloister (1900, 70), Tim Tatton-Brown states over the east cloister (1994, 21, 27), but as there were two galleries it may well be that both were meant.

The former infirmary range to the east contained the royal chapel, presumably the old infirmary chapel, and was probably used as the Queen's Lodging, the queen in question being Catherine Howard. Less likely the Queen's Lodging may have been in the long medieval buildings demolished in 1698 on the site now occupied by Minor Canon Row. This c.35m long, medieval building was more probably used to house servants. The Queen's Lodging consisted of a great chamber, chamber of presence, dining chamber, privy chamber and bed chamber. All we know for sure is that the Queen's chamber of presence was next to the King's chamber of presence.

It is unlikely that any further documentary evidence will be found in relation to the short lived palace. Perhaps the Cobham Hall archive is the best chance of finding such documentary evidence, although AW can't remember seeing anything in 2007 when he was undertaking some (admittedly pretty basic) documentary research of the hall (Ward 2008a).

Archaeological evidence: The new gravel foundations found below the lawn are regarded as the east range of the earlier cloister. The west range, if such existed, would presumably be on the site of the west range as we see it today. This would of course create a cloister area with a shorter east to west measurement. This would imply the measurement north to south would also be less, in which case the south range would (as perhaps it should in this early period) be on the inside of the town wall. Eventually archaeological trenches will tell us one way or the other. If that surmise is correct then the west and south ranges did not join with one another.

What has been regarded as Ernulf's east range was built to the east of what is assumed to be the remains of Gundulf's cloister below the lawn, but to add to our problems it is possible that Ernulf was the builder of those buried remains and that Gundulf's cloister was all of timber albeit, for the reasons previously stated on the same site. In the early thirteenth century the monks regarded the standing structure that we still see today, as being that of Ernulf (Flight 1997 152). This may be correct, but the problems in regard the architectural detail need to be taken into account.

On balance, due in large part to there being what looks like vertical stratigraphy (albeit pretty meagre) within the face of the east range coupled with the monkish tradition, the rubble work of the standing wall is regarded as that of Ernulf, but all the Caen Stone facing and architectural detail is regarded as being of the 1150s. Whether that means that the north wall of the Chapter House observed inside the vestry is all of that date as well is more debatable, but it does have to be either all of c.1155 or all of c.1120.

Archaeologically there is, also scope for finding out more of the 1540s palace. Part of a medieval or very early post-medieval building has recently been seen in the south-west corner of the grassed area. At the very least there should be remains of a royal cess pit and perhaps the lodging of the royal pages. These remains will probably not be more than 0.70m below the modern surface. Although no certain sign of anything to do with the 1540 palace was seen in Trench 1 dug in the grassed area, it is possible that flint surface (1588) formed a yard area to that structure, but no dating evidence was recovered. Part of the brick wall and a brick soakaway belonging to the 1805 prebendal house, demolished in 1937-39 were observed.

As far as the palace complex is concerned we may be able to go a bit further. In 1998 the present writer noted five buttresses added to the external face of the long medieval building demolished in 1698 and into which the early Georgian terrace, Minor Canon Row, was inserted in 1720-23 (Ward 2002). Bricks were also present, in those long buried buttresses and one can't help but think (at least AW can't help but think) that these were also 'Tudor' bricks and that this building may also have become part of the royal palace. Those bricks must certainly date to before the structure was demolished.

A late eighteenth century drawing mentioned above (Fig. 28a) shows gabled ends facing inwards (east) towards the cloister garth with bay windows and steps. An expansion in the surviving much truncated east wall of the west range, at its north end, is probably the base for one of these bay windows. Steps are shown leading up from garth level to the floor above the medieval undercroft. On their north, those steps are flanked by a buttress extending upwards to second floor level. The base of the buttress is still present, but there is no scar in the wall face to indicate the position of the steps. The last point provides a learning curve for archaeologists, when we look at upstanding structures let alone below ground archaeology. How much do we actually miss because all trace has gone?

The east range

Documentary evidence: The documentary evidence for this range has been mentioned above and other than a note on Hope's work in the undercroft of the dorter is not repeated here.

Less well known than these studies of the decorated side of the dorter wall is the 1884 work of William St. John Hope to the east of the west wall within the dormitory range itself (Fig. 73). In the late nineteenth century Hope excavated a series of trenches within the yard area. He tells us that whilst he was, 'allowed to make such excavations as I pleased in the yard' (Hope 1900, 43). He in fact did not excavate any of the central pillars (ibid. 44), he only searched for the responds up against each wall. He tells us that two of the responds on the east were still visible at then ground level. Also, in 1881, another had been found when digging an ash pit up against the west wall and was still visible and in a note at the base of page 43 he tells us the next respond to the south had also been excavated and built around. Both of these responds, abacus, capital and shaft, can still be seen.

He tells us that the division between the third and fourth bays on the east was different from the others for it had a squared pilaster buttress rather than a semi-circular shaft. He regarded this as being the position of either a wall dividing the undercroft into two, or representing the position of more massive piers and arches so as to support a partition wall at first floor level. in the dorter itself.

Architectural evidence: The west face of the east range west wall is, because of its decorated arcade and the artistic detail of the doors, one of the most studied areas of architecture at the cathedral. This frontage has been studied in considerable detail for over a hundred years, but there are still doubts as to the date of the decoration. Traditionally the dorter is assigned to the time of Ernulf (Bishop 1114- 1124) but, as understood by the present writer the latest suggestion is that the whole wall, both the decorated Caen Stone and the Ragstone rubble dates from c.1160 (McNeil 2006). In which case where is Ernulf's work?

3D model of the dormitory portion of the Cloister Garth east range comprising entrance archway and two blocked windows into the dormitory.

According to Tim Tatton-Brown the centre of all three upper medieval windows in the west wall of the Chapter House had their chills lowered so as '.... (presumably to make them into doorways)... .' (1994, 21). These doorways supposedly gave access to a corridor built above the cloister and, if extending the whole length of the east range, effectively forming a long gallery. If this is correct the series of joist holes just below the apex of the robbed out blind arcade arches presumably belong to the 1540s alterations. Whether this floor was ever finished is a debatable point (see above, page 58).

3D model of the archway and tympanum typically interpreted as once having led to the stairs between the Chapter House and Dormitory. The tympanum is thought to represent Moses and the burning bush.

Internally no sign of any reduction in the window cills can be seen today, all three have been madeup with modern tiles and cemented stonework in a series of 'steps', extending the whole width of each window. This hints that the cills originally sloped downwards from external to internal wall face. Although this repair work 'looks' older it has presumably occurred since 1993 when conservation work was undertaken. Indeed this is exactly what appears to have happened. The corbels below the cills had brickwork supporting them prior to the conservation work. However, because there is no sign of any other corbel line, it is considered here that they were repairs to the medieval supports. What this does mean is that the Tudor gallery over the cloister roof varied in height. A higher level in front of the Chapter House and at a lower level along the length of the rest of the east range. We can see that to the south of the Chapter House there are two levels of corbels. The lower level (themselves inserted into an earlier wall) supported the medieval pentice roof. The higher level corbels, here with much Tudor brickwork around, are also inserts and these can be regarded as part of Henry VIII's rebuilding, but whether there were medieval corbels in the same holes we have no way of knowing.

3D model of the archway into the dormitory.

If we count the Caen Stone courses over the dorter door the irregular edge shows us that at least eight courses have been lost and replaced by rubble. Some of that rubble, certainly the curved cope, in the uppermost courses is probably of nineteenth century date but some , even above the higher group of corbels, has to be earlier than c.1540. The irregular survival of the Caen Stone coursing and the expectation that all the c.1155 corbels would be horizontal, in other words at the same level as those below the Chapter House windows is telling us that, with the exception of the latter, all the midtwelfth century corbels have gone. Whilst the Chapter House corbels have been reset, in c.1540 and c.1990 that there is only one level of corbelling is telling us that had to be their original height.

The lower level of corbels are contemporary with the rubble walling above the Caen Stone courses. There is no reason why the rubble walling shouldn't be the work of Gilbert de Glanville (Bishop 1185 to 1214) who is described as 'having finished the cloister in stone', (Hope 1900, 11). There is certainly no evidence to the contrary.

Admittedly, we do not know how far to the south the Caen Stone courses may have extended, but conceivably they could have continued for the whole length of the east range. We might even be so bold to say that another twenty of so courses, up to their maximum surviving height, have been lost.

At ground level two medieval windows were converted into doors, both of which today have what appear to be 'Tudor' brick jambs. However, these bricks are 'fakes' and were probably inserted in 1935 when the garth area took on the form we see today. However, one of the passage-ways, cut through the medieval wall, has a brick arch and these are different from those in either jamb and are almost certainly genuine mid-sixteenth century brickwork. some of the bricks in the jamb of the southern blocked door are also original Tudor bricks, but may have been reset.

3D model of one of the blocked windows to the south of the dormitory stairs.

There may, and the word may needs to be stressed, some vertical stratigraphy within the standing fabric. The whole of one jamb survives for the southernmost window. This jamb, the southern, survives for a height of c.1.40m, the lowest course of the northern jamb also survives for a height of c.0.20m. There is no surviving portion of the arch of the window. However, it presumably sprang from the highest surviving course of the jamb, for the arcade arch situated in front, springs from that level and would be the same diameter as the window arch. Both window jambs have a c.1160 shaft in front of them. The question is, are the shafts and their arch the same date as the jambs and its own (albeit destroyed) arch? The window jambs are made from Caen Stone, in places scorched, but whether in the fire of 1137 or that of 1179 we are unable to say. The arcade shafts are also scorched and as these date from c.1155 this damage must be in the fire of 1179 (or, if looked at objectively, from a later fire about which we know nothing). If the window is the same date as the arcade why not build suitably shaped jambs at the forward position rather than flush with the rubble walling to the rear? In the view of this writer the shafts look to be out of position, they partly hide the Caen Stone jambs. However, whether they were placed in front of the jambs a few days after the latter were built, perhaps after a change in plan, or a few decades later after the fire of 1137 we, yet again, have no-way of knowing. The only way it might be possible to obtain a clear stratigraphic picture would be by removal of a small part of the arcade and some of the Caen Stone ashlar blocks above. If a face, continuous with the rubble to the rear of the shafts, continues upwards, behind the arcade arches, then it would be a reasonable deduction that this was Ernulf's stonework, no doubt at one time plastered, fossilised within the c.1155 decorated face.

We can say with certainty that the infilling of the window with Ragstone rubble and other material is not confined just to the window area itself. The coursing within this window covers the stump of the northern jamb and if we observe carefully we can see that it continues northwards all the way to the next window, now a blocked doorway. This refacing presumably dates to c.1540 or perhaps more likely slightly later (c.1560) when the idea of building a palace had been abandoned. What this means is that a length of at c.3.60m of rubble facing behind the shafts is of post-Dissolution, rather than medieval, date.

The main dating problem arises in regard the date of the standing range. Traditionally it is regarded as being built by Ernulf. The later architectural detail within that range has long been regarded as representing a refacing after the fire of 1137. As far as AW can see there is no actual sign of a reface. Internally, within the late medieval vestry (the old library) neither the foundation or the upstanding north wall of the Chapter House showed any sign of rebuilding, therefore that wall, at the very least, has to date to either c.1120 or c.1155, not both.

Archaeological evidence: In 1937 the East Range cloister walkway was dug down to its present, more or less the medieval, level. Over the centuries material had accumulated within the alley way. A small excavation was also undertaken within the Chapter House which is why the ground surface is at two different levels.

In the 2014 to 2015 project a service trench was dug adjacent to the north wall of the Chapter House. This work has been described above (see above, page 57).

The undercroft below the dormitory has long since been infilled, probably in the 1560s when the Dean and Chapter demolished the monastic buildings and was presumably cobbled over when it became the Deanery kitchen yard sometime in the seventeenth century. The yard was cobbled until well into the twentieth century, when it was already part of King's School, and a few photographs dating to the 1920s show its then appearance.

South Range

Little of the South Range survives. In 1772 Samuel Denne tells us that there were still columns and arches facing Minor Canon Row (Denne 1772 ; 1816, 86-7). Hope makes no note of these, but was able to record (1900, 48) the presence of the seven buttresses and a wall across the refectory at its west end creating a 4m wide room. This wall had a door at its south end and had only recently been demolished. There was another cross-wall at the east end creating another room, the 'Dark Entry'. Other than those features he saw nothing and one gets the impression the floor levels of the undercroft were not revealed or if they were he missed them. Three structures, of which the western may be part of the medieval kitchen, are shown on Figure 27c.

Very little if anything of what was originally the Roman town wall is actually Roman, it has seen much refacing, and even if any Roman work is visible it will be core. Part of one capital and one shaft of the cloister walkway can be seen. These were hidden from Hope by the house of the third prebend, but he was able to see the thirteenth century lavatorium for the washing of hands for the monks prior to entering the refectory and a superb drawing appears in his 1900 article.

Returning to the seven buttresses, seen by Hope. These were of course attached to the refectory of Hamo de Hythe not that of Ernulf. Having said that, whether the refectory was actually rebuilt in our sense of the word in 132? or merely underwent an extensive repair we have no-way of knowing. Ernulf's refectory was presumably built on the berm between the old Roman town wall and the inner edge of the defensive ditch. Over time that slope would almost certainly have moved and it may well have been necessary to rebuild and / or buttress the south wall. Whether the ditch had been infilled in 132? or c.1120 or any date in between we again have no-way of knowing. The infilling must have happened before the long building to the south was constructed and this is assumed to be the 'long bakehouse' built by Hamo. If the pit and floors found by Chaplain c.1960 (see above, page 64) have been correctly dated to the thirteenth century then the ditch must have been infilled in that century or earlier. If Ernulf's 'new bakehouse' was on the site of Hamo's 'long bakehouse', as suggested by Hope (1900, 52), then the infilling of the Deanery Garden Ditch, at least in this area, must have taken place by c.1120. Such an early date has to be doubtful, if for no other reason it implies there was no ditch on the south side of the city until that of c.1225 was dug. That ditch would have to be the King's Orchard Ditch the material of which is usually regarded as having infilled the DGD, it is hard to see where else the excavated material could have gone.

West Range

Philip McAleer (1993) has written the only really informative article on this range. It is barely mentioned by Hope very largely because it was still covered by the house of the third prebend in his day.

West Range of the Cloisters

Documentary evidence: There appears to be none. We have no record of who built the west range. McAleer tells us that architecturally there is no reason why it should not have been Ernulf (McAleer 1994), but Colin Flight tells us it was first built in stone in the mid-twelfth century (Flight 1997, 153).

Ernulf is recorded as building an east range (including a Chapter House) and a south range. No mention is made of a west range. However, just because the latter is not mentioned that does not mean to say it wasn't constructed or in the process of construction at the time he was bishop, and it has sometimes been put forward as having been the east range of Gundulf's cloister supposedly built to the south of the nave. If this range was Gundulf's time we can say it would have to have been the east range, not the west range of his cloister garth.

Architectural evidence: McAleer brings to our attention the architectural detail, in the form of a series of shafts with capitals within the south room of this range. He saw no reason why this detail should not date to the, 'first quarter of the twelfth century', with the implication that the west range, as with the east and south ranges, was of the time of Bishop Ernulf (McAleer 1994, 20). We can, of course, point out that the date range given would include the last years of Gundulf's bishopric.

In McAleer's article there is a wonderful c.1798 drawing of northern portion of the east wall of the West Range drawn by William Alexander (Fig. 28a), is depicted. This range was pulled down early in the nineteenth century. On the drawing, other than a Romanesque window high up in the northernmost part of that wall, most of the structure shown may well be timber-framed and has all the hallmarks of being very late medieval or early post-medieval in date.

Archaeological evidence: Despite there having been archaeological observations and excavation along and adjacent to the west range none have helped date the original structure.

Irvine's observations below the south wall of the transept show that an earlier wall existed at that point, but not how it relates to either the west range or an earlier transept. It is assumed to be of late eleventh century date, but it could just as well be of any date prior to the building of the transept in its present form in the thirteenth (c.1240) century.

In 1938 there was an excavation in the south end room of which couple of photographs exist. In 1982 there was an excavation on the site and just to the south of the 1980s south porch. Parts of the late medieval tile floor of the west cloister walkway were found in situ (Bacchus 1985) and the detail than discovered has been added to Figure 63. As has the detail from trenching undertaken by Graham Keevill in 2010a when he tile floor was found and dug through. Several walls of one of the prebendal houses were found along with walling which may have been of medieval date.

Whilst the excavations in the area of the West Range in 2014-16 were limited we also have to take into consideration the work and observations that have been undertaken in the area of what is now the south aisle of the cathedral, for we have to remember that eventually the north wall of the west range became part of that structure.

We can see that the quoin within the south quire aisle is the earliest detail in this area, but other than saying it is Norman, in year terms we have no idea of when. It is almost certainly pre-c 1140, it could easily be 1120 or 1100 or even c 1085. Whilst the architectural detail at the south end of the west range may well date that area to c.1120 it does not necessarily date the north end of the structure. Even the window shown in the drawing of c.1798 (Figure 28a) at the north end of the range has another larger arch above. Is this an earlier window or a relieving arch.

If we accept that the evidence from the garden of the Bishop's Palace is showing that there was no cloister there in the time of Gundulf and that the remains found in the cloister garth is his work, then there is no reason why the west range, or at least part of it, should not represent the late eleventh century west range of his monastic enclosure.

The Cloister Garth

After the demolition of Gundulf's ranges the garth was, apparently, kept as a mown lawned area (as now) for the whole of the medieval period (Hope 1900, 29) and apparently used for the cleaning of carpets. This long standing lawn goes someway to explaining how the foundations of the late eleventh century east range survived so well.

With the limited trenching undertaken within the lawned area, and very surprisingly, remains of very impressive gravel foundations appeared. That these foundations supported a stone structure was shown by the small areas of masonry that survive surviving on the northern foundation of this building (see above, pages 54 to 57).

Alan Ward

Keevill Heritage LTD.

Extracts from Hidden Treasures, Fresh Expressions; Archaeological Surveys, Excavations and Watching Briefs at Rochester Cathedral 2011-2017

Further studies

Bishop Gundulf's cloister, c.1080-1114

Archaeologists Alan Ward and Graham Keevill discuss recent archaeological investigations beneath the Cloister Garth revealing what is thought to be the foundations for Bishop Gundulf’s short-lived cloister.

The most exceptional surviving architecture from Ernulf’s cloisters is the Chapter House in the North East corner. The Romanesque capitals of the doorway rival those of the Cathedral’s West Facade, decorated with the heads of Kings, demons and dragons.

The Chapter House, 12th century

The Chapter House was constructed in the twelfth century and survives in ruin, having lost its roof in the 18th century. It was where the monks met daily to discuss the business of the day.

EXPLORE

Explore the studies, conservation and excavations revealing the sites 1,400 year history.